Scientists: Three years left to reverse greenhouse gas emission trends

We have until 2020 to reverse the trend of greenhouse gas emissions to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, say scientists. Missing the deadline will cause severe economic disruption.

A commentary published in Nature and led by Christiana Figueres, vice-chair of the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy and Convener of Mission 2020, calls upon leaders of the G20 to commit to reversing global emissions of greenhouse gases by 2020 ahead of their July summit in Hamburg.

Reversing emission trends in the next three years will allow a smooth transition to a global fossil fuel free economy while keeping us within the remaining carbon budget necessary to meet the goals set under the Paris Agreement, say the signatories of the commentary.

Among the co-authors are scientists from around the world, including Johan Rockström, executive director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University, Sweden.

Co-signatories include scientists such as Professor Katherine Richardson, leader of the Sustainable Science Center at the University of Copenhagen, along with business leaders, economists, analysts, representatives of non-governmental organizations and worker’s unions, as well as religious leaders. A full list is available here.

“Our call is not only to stabilise [current emissions], but also to chart a course of descent from where we are currently at over 40 gigatonnes a year globally to net zero by 2050,” says Figueres, adding:

“This cannot be done overnight. That is why science is clear about the fact that in order to ensure the possibility of a smooth transition of economy we have to start the descent now, so we can take a few decades to go from where we are now to a net-zero [fossil fuel] global economy.”

“Changing our energy system is not enough”

Whereas the public discussion around climate change is often focused on “if” we have a problem with climate or “whether” we need or can afford to act, the commentary presents evidence that demonstrates how the world is already responding to the climate change challenge, says co-signatory Professor Katherine Richardson.

“Our energy system is advancing [towards renewables] at a dramatic rate and it is economically viable. It also demonstrates, using data, that changing the energy system is not enough—we need to look at food, transport, water, infrastructure and so on,” she says.

But most importantly, the commentary argues that change is not happening as quickly as the scientific evidence says it needs to, in order to meet the Paris targets, says Richardson.

“Now it’s really our moment. And the bottom line is that this is not a discussion of whether we believe that human made climate change is happening, or whether we can or should do something about it. Rather, how we can most cost-effectively speed up the rate of change in order to be able to meet the Paris targets and ensure the best possible chance of a prosperous future for our children and our grandchildren,” says Richardson.

What is the math?

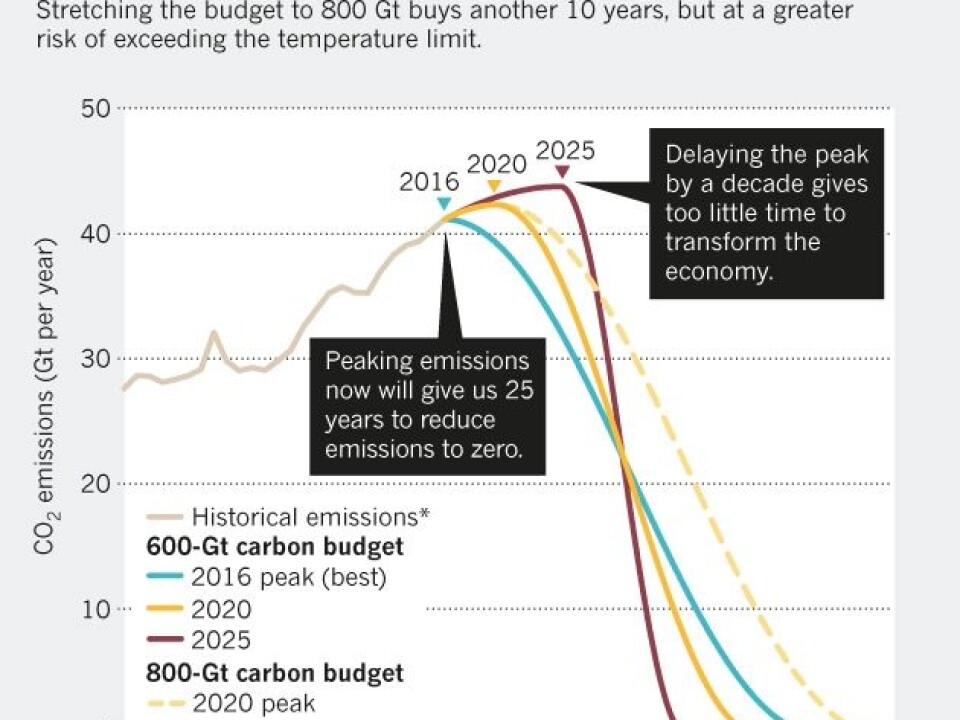

The commentary is anchored in a so-called carbon budget. This is the amount of CO2 that we can emit and still meet the targets set by politicians during the COP21 meeting in Paris, to limit global temperature rise to between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius.

Current estimates of this carbon budget range between 150 and 1,050 gigatonnes of CO2 depending on the precise method and data used to calculate it.

The lower limit could be reached in four years if emissions continue on their current track, while the mid-point of around 600 gigatonnes could be breached in 15 years, according to the commentary.

Whatever the true budget is, exceeding it will mean warming above and beyond the 2 degrees Paris goal and reversing current emission trends early gives more time for the global economy to transition away from fossil fuels, says Richardson.

“So this is a question of using the best of science to say that if we’re going to use the entire garbage dump and the entire budget will disappear within 4 to 16 years, then to be able to make the most cost-effective transition without bringing ourselves to our knees, we have to peak now or very close to now, and we’re saying 2020,” she says.

The 6-point plan

The plan covers six sectors: energy, infrastructure, transport, land use, industry, and finance.

It includes goals such as achieving 30 per cent of global energy production through renewables by 2020 and retiring all coal-fired power stations and not building any new stations after 2020.

In transport, electric cars should make up 15 per cent of new car sales—it currently makes up just one per cent. And they call for commitments to double the use of public transport in cities, increase fuel efficiencies for heavy-duty vehicles by 20 per cent, and decrease greenhouse-gas emissions from aviation per kilometre travelled by 20 per cent.

Elsewhere, policies are required to encourage more forest growth, reduce emissions from industry by 50 per cent, and to boost investment in climate adaptation and mitigation to the tune of 1 trillion USD each year—largely via private investment.

The co-authors argue that to reach these goals will require rapid escalation of existing policies and greater communication of science to guide political decision making over the next three years.

The plan has been met with cautious praise from many scientists, including Dr. Glen Peters, an expert in international trade, climate policy, and greenhouse gas emission metrics at the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research in Oslo, Norway.

“The mitigation challenge is immense, requiring deep emission cuts in all countries, rich and poor. To get emissions to zero in the space of decades requires an unprecedented technological and behavioural revolution. Powerful incumbents may resist, and so we need smart ways to make the low carbon path irresistible,” said Peters to CarbonBrief.

He added:

“As a scientist, my bones are made of scepticism and I see no point in optimistically walking off a cliff. There is a place for certain people to express optimism, but others have to ensure we can deliver on that optimism.”

“The Fossil-free economy is already profitable”

Figueres is optimistic that the 2020 deadline is feasible.

“We have finally realised that this is not an ‘either or’ situation. So it’s not, either we grow the economy or we protect environment. This is about the very important coincidence of imperatives whereby we can create jobs, we can recreate communities who have lost jobs, we can jump start the economy, and we can provide long term stability to growth.”

“Energy related CO2 emissions have been flat for three years in a row, while our global GDP increased by 3.5 or 3.4 per cent on yearly basis. So there’s reasons to believe that we’re making progress,” says Figueres.

Richardson agrees.

“We really do have the tech to do this now--we didn’t 10 years ago, but we do now. Knowing how to solve a problem and having the equipment at your fingertips makes a big difference,” says Richardson.

Johan Rockström, executive director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University, Sweden, on how we can "bend the curve" on emissions by 2020. (Video: Stockholm Resilience Centre TV)