Intense exercise inhibits cancer in mice

New research shows that cancerous tumours grow more slowly in mice that exercise more. Scientists now plan to test the effect in humans.

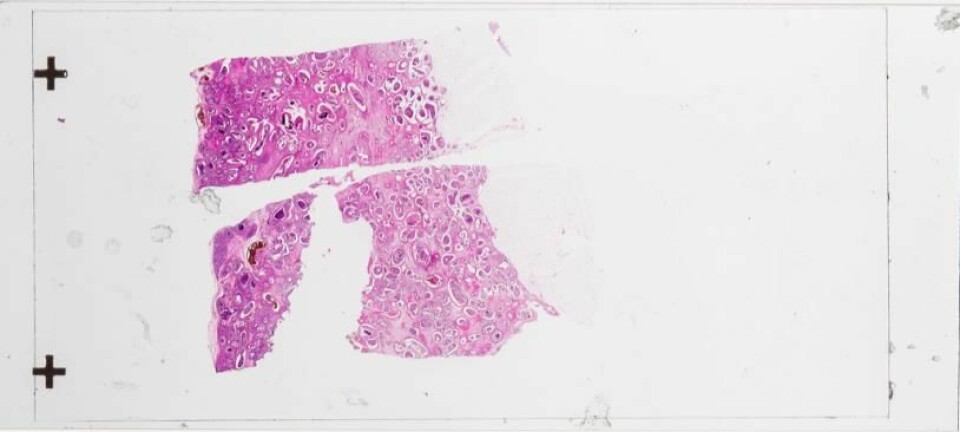

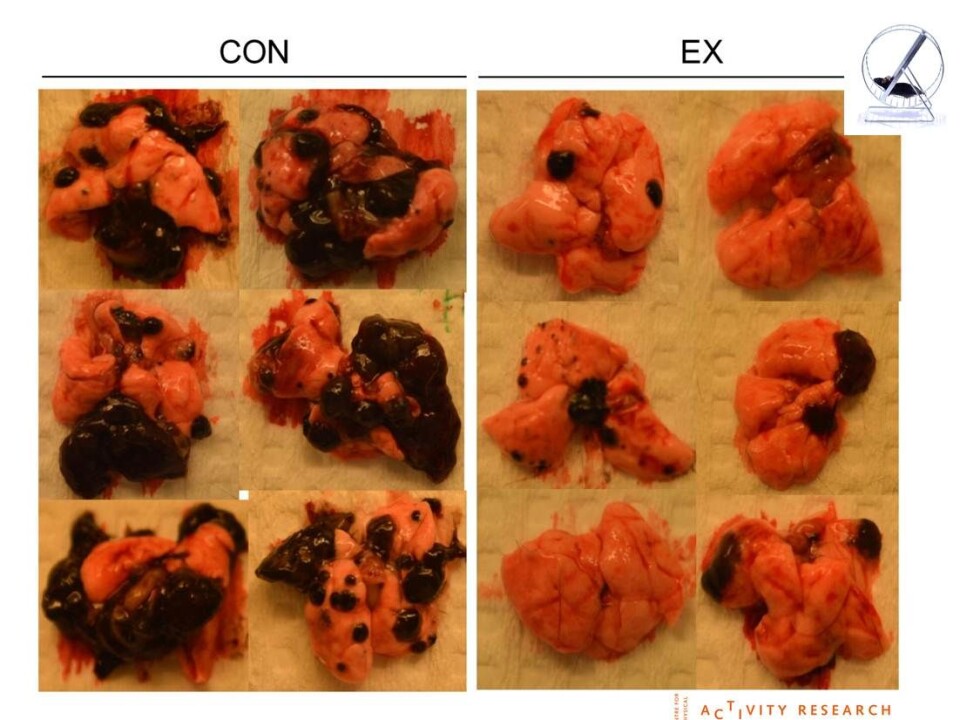

A new study on mice shows that regular, intensive exercise can inhibit the growth of cancer tumours.

The scientists behind the new research studied the effects of a four kilometre daily run in mice with cancer. The running regime reduced the size of their tumours by 50 to 60 per cent.

"Exercise reduces the growth of cancer tumours,” says co-author Pernille Højman, a postdoc at Center for Physical Activity Research, Denmark.

“It doesn’t apply to just one specific type of cancer, but generally [to many cancers]. We see it especially in malignant melanoma, liver, and lung cancer," says Højman.

The results are published in the scientific journal Cell Metabolism.

Training helps turn the immune system against cancer

The intense training routine speeds up the body's fight against cancer, says Højman.

"The exercise activates adrenaline production and this activates the immune cells in the bloodstream. It’s these cells that recognize viruses and bacteria, and also tumour cells," she says.

The activated muscles produce so-called IL-6, a chemical that helps the immune cells to attack the tumour.

"The cells enter the blood stream with the adrenaline, but they also need to enter the tumour itself. Here, IL-6 is essential. We’ve found that aerobic exercise is a kind of switch that can turn the immune system to fight against the cancer," says Højman.

Training must be intense

The workout needs to hit a certain level of intensity to achieve this effect, and a short low-energy jog is not enough.

For patients to achieve the anti-cancer effect, IL-6 has to increase, and the chances of this happening largely depend on the patient’s physical condition, says Højman. Patients who are already in good physical shape actually produce IL-6 more slowly than less fit patients.

“It just shows that even those who are in bad shape, see an effect. [Patients] shouldn’t be deterred [if they are out of shape], as they see faster results,” says Højman.

Ideally, patients should exercise hard or long enough to the extent that they become out of breath and are unable to hold a conversation, she says.

Depending on how fit you are already, this could be anything from 20 minutes to an hour of intense exercise.

Højman stresses that poor physical condition should be thought of as an advantage--only an indication that a shorter workout might be needed to achieve the desired result.

Strong effect surprises scientists

Højman herself is surprised by the results.

"Many studies have shown that quality of life is improved by exercise. For example, we know from population studies that cancer patients who are declared healthy, have a better survival rate when they exercise," she says.

"That's why we thought [we’d see] an effect, but not such a significant one. The most surprising thing is that we can show it’s consistent and we found it in all the models we studied," says Højman.

Optimism over the benefits of exercise to fight cancer

Højman is optimistic about the implications of the new study and how it relates to many types of cancer, such as melanomas.

"Melanoma is known to be easily recognisable to the immune cells. So it makes sense that this cancer is also susceptible to these immune cells," she says.

"The sticking point is whether it works to the same extent in other types of cancer that are not as sensitive to the immune system, such as prostate and breast cancer. We have good indications from the tests, but it’s too early to conclude anything [definite] from them yet," says Højman.

Nonetheless, she is "fairly optimistic" that the results can be applied from mice, to humans.

Colleague: An exciting project

Professor Morten Høyer from the Department of Oncology at Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark, was not involved in the study himself, but thinks that it is an exciting project.

"We’ve had the idea for a long time, that patients who exercise fare better than those who don’t. But we didn’t know which was the chicken and which was the egg. Did patients get better for some other reason, which enabled them to exercise, or did they fare better because they exercised?”

"This study shows that there may be a good biological explanation for why exercise is good, and I think it looks convincing and promising,” says Høyer.

Next step: Tests in humans

Højman will now extend the research to cancer patients.

"[The next logical step] is to find out how it works alongside chemotherapy and especially with immunotherapy treatments," she says.

It could, for example, be effective alongside so-called checkpoint blockade treatments--one of the newest forms of cancer treatments.

Cancer tumours send out signals to trick the immune system, so that it does not recognise them as harmful. But checkpoint blockade medicines, effectively switch off these signals.

"If we can let immune cells get inside the tumour, while the tumour can’t turn off [these signals], then it could hopefully provide an enhanced response [to the treatment]," says Højman. "The first step will be to test how immune cells respond in healthy people, and then we would like to proceed with cancer patients later this spring."

Høyer thinks this is a good idea.

"It makes good sense, and the same could actually be considered in relation to radiotherapy. There is nothing to suggest that radiation stimulates the immune system, so it makes sense to try [exercise treatments] alongside it," he says.

------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex