Telomeres do not determine your mortality but they protect against cancer

Researchers have found that short telomeres do not lead to increased mortality. Surprisingly, they reduce the risk of dying from cancer.

A new study might lead to new and better cancer treatments.

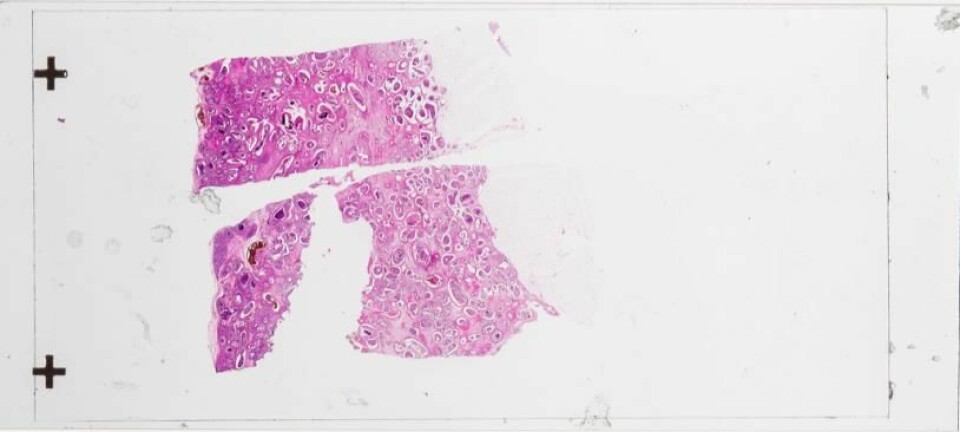

In the study, researchers examined the telomeres that protect the ends of our chromosomes. Each of us has telomeres of different lengths which wear down and become shorter as we get older.

Until now, scientists believed that short telomeres were associated with increased mortality. What’s more, if you smoke, have an unhealthy diet, and exercise too little, you risk wearing them down even faster and further shortening the telomeres you are born with.

Now, scientists behind a new study conclude that the telomere length that we are born with does not have an impact on our mortality.

In fact, they found that it is an advantage to be born with short telomeres in relation to cancer mortality. A result that surprised them.

"For us it was a rather surprising result," said Stig Bojesen, a professor at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Copenhagen and consultant at Herlev Hospital in Denmark.

"We found something quite interesting in our genetic study, namely that telomeres do not affect general mortality, but when we look at cancer mortality, we find the opposite of what we expected: People with a predisposition for having short telomeres laso have a decreased cancer mortality,” says Bojesen.

The study is the largest of its kind

Bojesen explains that small deviations in the length of telomeres causes a lower mortality in people with shorter telomeres.

Participants in the genetic analysis had on average one telomere length of 3,800 base pairs, and each time this telomere length shortened by five per cent, the rate of cancer induced deaths likewise decreased by 14 per cent.

Bojesen and his colleagues collected data from 64,000 Danes as part of the genetic study, and it is, according to Bojesen, the largest worldwide study of telomeres and mortality rates in terms of the amount of data used.

Small differences have great power

Professor Kaare Christensen, head of the Danish Aging Research Centre at the University of Southern Denmark finds the new study interesting.

"It is surprising how small the difference in telomere length is in those with genetic predisposition, and that this is enough for there to be a connection with cancer mortality," says Christensen.

He calls the new study "solid" and points out that these results are only possible due to the large amount of data indcluded.

Maintaining telomere length may be a disadvantage

Despite the association with lower rates of cancer mortality, Bojesen explains there may be downsides to these genetically short telomeres as they are vulnerable to further shortening given an unhealthy lifestyle.

"People have long telomeres because their cells are adept at maintaining and repairing them. The downside is that the person’s cancer cells are also proficient in maintaining their telomeres and so avoid the growth retardation process that is usually associated with short telomeres. If you can directly attack this repair process, you can, in principle prevent cancer," says Bojesen.

He explains that previous studies of possible links between mortality and telomeres have been observational, and that they therefore have not been able to say anything about causation.

Hope for new cancer treatments

The new discovery, according to Bojesen, provides hope that we may one day produce new treatments against cancer.

The method is called telomere-inhibition and aims to stop the cancer cells maintaining their telomeres.

This principle has been studied as a possible cancer treatment for around 10 years.

"The results have so far been disappointing. But our study provides a theoretical argument to continue with this type of medication. This medication inhibits the machinery of cancer cells that maintain the cancer cell's telomeres," says Bojesen. He adds that it will of course be a challenge for the developers of these new medicines to deliver the treatment into the cancer cells and make it work in practice.

------------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex