Less ice in Greenland 3,000 years ago than today

A new method for dating ancient sea shells reveals that the Greenland Ice Sheet was smaller between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago than it is today. The new study also indicates that the inland ice is more robust than previously thought.

Scientists have developed a new method that can determine how large the Greenland Ice Sheet was in the past.

The method allows the researchers to measure the concentrations of various forms of amino acids in old shells of clams in order to determine their age.

This enables the scientists to figure out when various areas of Greenland were covered by the sea, where the clams could live, and when there was ice – in other words, how far the ice sheet grew.

The new study suggests that the western extent of the ice sheet was at its smallest in recent history between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago.

The Danish researcher in the international team explains:

”Scientists have long known that there was a period after the last ice age when the Greenland Ice Sheet was smaller than today, but we did not know exactly when that period was,” says geologist Ole Bennike, of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS).

”With our new technique, we can see that this period was between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago, which is later than we thought.”

The inland ice is robust

The results of the new study paint a picture of the Greenland Ice Sheet as being more robust than previously thought.

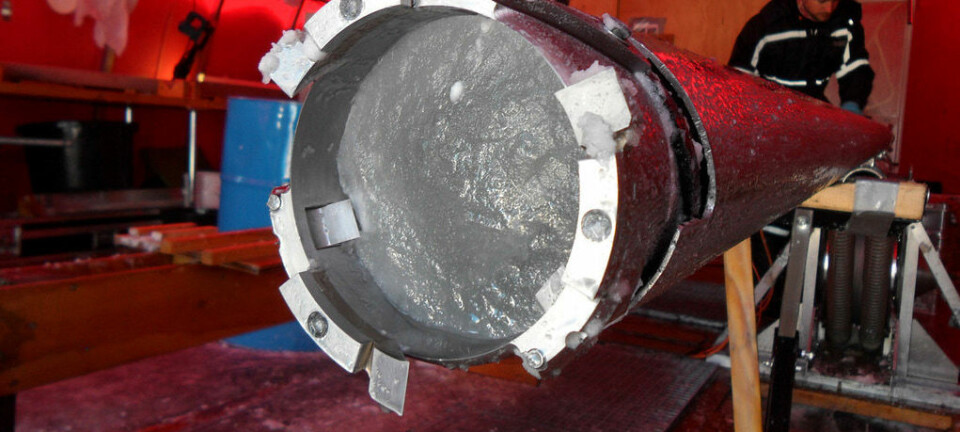

The period from 3,000 to 5,000 years ago is consistent with analyses of marine sediment cores, which show that during this same period, more marine invertebrates lived in the sea in West Greenland. This suggests that it was probably the warmer seawater at the coast of West Greenland that had the greatest impact on the ice sheet.

Scientists often say that the ice sheet will eventually reach a point where its decrease in size will become irreversible, i.e. that it cannot regain its former size.

“The new study suggests that the ice sheet will start to grow again if it becomes colder. However, according to all climate models the temperature will increase in the future,” says Bennike.

Improved understanding of the ice sheet

Scientists know that the climate around Greenland became warmer towards the end of the last glacial period some 10,000 years ago. The exact time at which the inland ice shrunk to its smallest size has, however, remained unknown.

The new findings indicate that the ice reached its minimum after the sea in West Greenland started to become warmest around 5,000 years ago.

”The period from 3,000 to 5,000 years ago is consistent with analyses of marine sediment cores, which show that during this same period, more marine invertebrates lived in the sea in West Greenland. This suggests that it was probably the warmer seawater at the coast of West Greenland that had the greatest impact on the ice sheet.”

Affordable analysis method

The new study not only adds new insight into the history of the Greenland Ice Sheet; it also presents a new tool that researchers can use to date large numbers of shell fragments in a much cheaper way than using radiocarbon dating.

The new method is based on the fact that when an organism dies, its amino acids slowly change from a so-called L-configuration into a D-configuration.

Since this process occurs over time, the ratio of D-forms to L-forms reveals the age of a fossil, in this case sea shells.

“This is a technique that is normally used to date fossil material that are between 50,000 and 2 million years old. In our study, however, we managed to study a much shorter time scale by analysing the ratio between the L- and the D-forms of the amino acid aspartic acid. L-forms of this amino acid are transformed to D-forms much faster than in other amino acids,” explains Bennike.

”The technique is also much cheaper than carbon-14 analyses. Our amino acid analysis is about 15 times cheaper than a radiocarbon analysis.”

----------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther