This is what a 50-million-year-old bat looked like

Scientists have for the first time determined the colour of an extinct mammal: a bat that lived 50 million years ago.

Scientists have determined the colour of extinct frogs, birds, tadpoles, and bats from the fossilised remains of the pigment melanin. This is the first example of using fossilised melanin to determine the colour of an extinct mammal.

According to the new study, the bat would have been reddish-brown coloured.

Co-author Jakob Vinther from Bristol University, UK, is not only interested in the bat’s colour, but also what this colour might tell him about how the animals once lived.

"Once we know an animal’s colours we can say something about their lifestyle. For example, we can see if they tried to camouflage themselves or whether they advertised themselves with a colourful plumage," says Vinther, who was the first to use fossilised melanin to determine the colour of an extinct animal.

He has previously shown that a grey dinosaur had a reddish-brown comb on the top of its head--a clear sign that it wanted to be seen.

The new study has just been published in the scientific journal PNAS.

Advanced techniques to discover animals’ colours

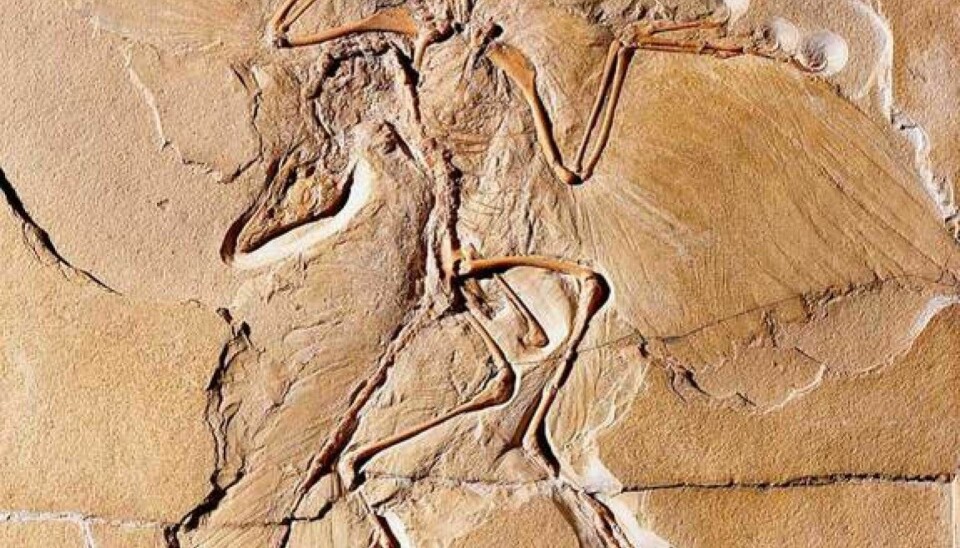

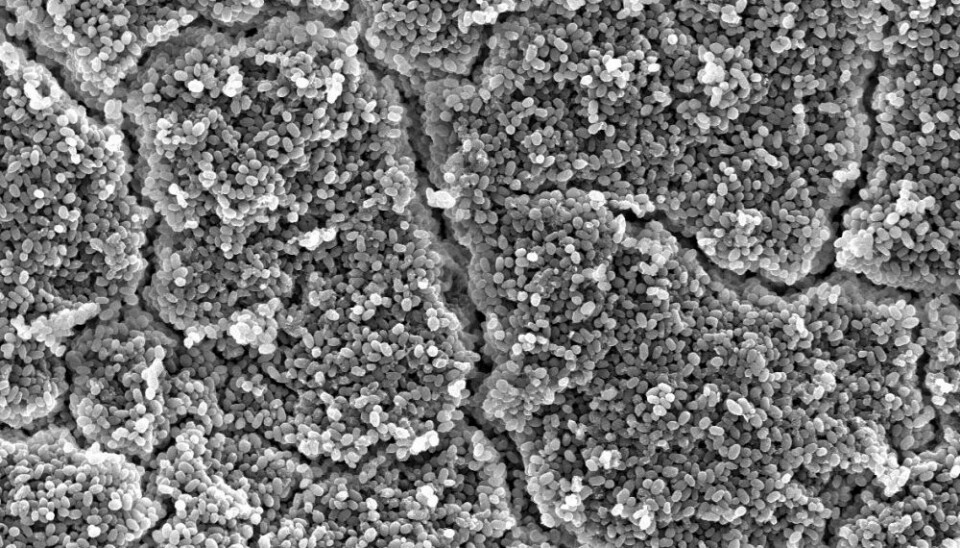

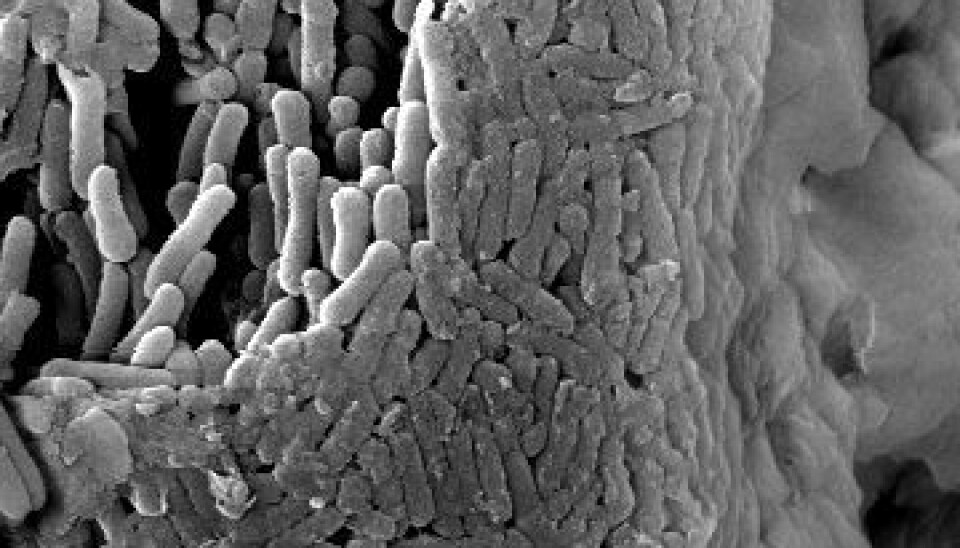

In the study, Vinther studied fossils under an electron microscope to find visual signs of fossilised melanin, which he could then use to determine the animals' colours.

Right now, the range of colours indicted by melanin is still rather limited. The shape of the melanin grains can indicate black (elongated grains) or red (rounded grains) colouring, whilst the location of the melanin grains indicate the potential for grey colouration.

Vinther also analysed the fossilised melanin grains with an advanced technique to determine their chemical composition.

By comparing the results of the chemical analysis to samples from modern melanin grains exposed to temperatures and pressures that mimic millions of years in the soil, Vinther was able to determine both the differences in the pigments and the colour of the individual animal.

"This technique enables us to analyse really degraded samples where the pigments no longer look like pigments as we know them today. Using this technique, we can now determine what the animals once looked like," says Vinther.

Colleague is excited, but would like more data

Johan Lindgren is an associate professor of geology at Lund University, Sweden. He was not involved in the new study, but he is one of the few scientists in the world who also uses the same techniques to study fossil melanin.

Lindgren thinks the new study is interesting, and he is especially pleased to see that Vinther is using the technique.

He also suggests that the study adds weight to a relatively new field of research, which has been debated for many years.

"It adds support for the use of both chemical and morphological analyses to determine the pigments in fossils. I'm really happy to see it, and it’s the only way forward. Eventually, there’ll be no doubt that these pigments do indeed exist in fossils," says Johan Lindgren.

-----------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex