Space travelling cancer cells filmed for the first time

A team of scientists have filmed living cancer cells in space for the very first time.

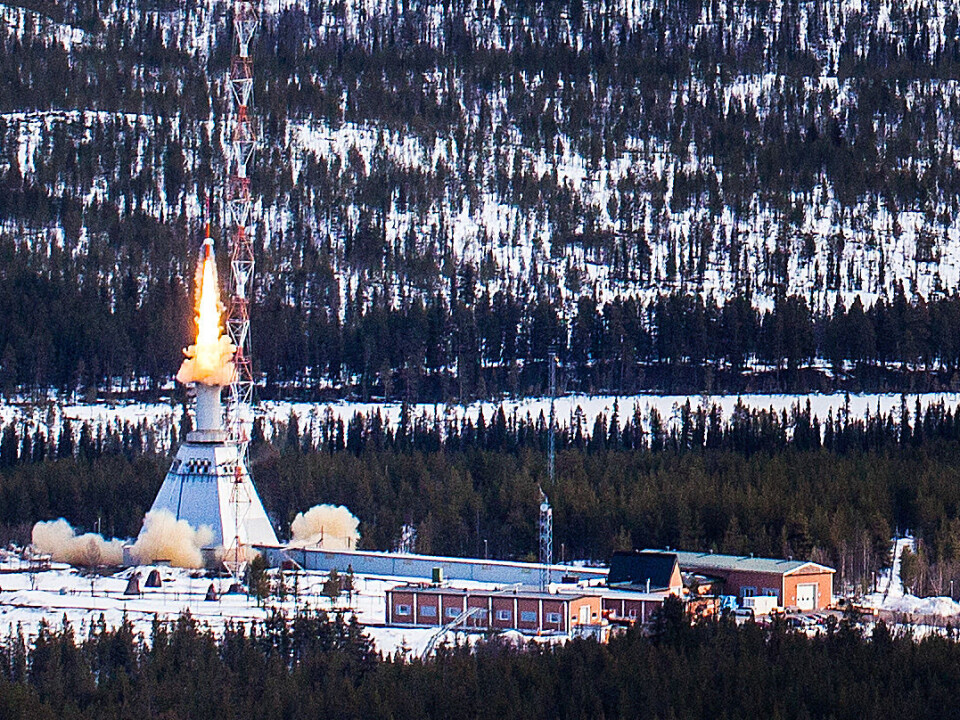

After a 20-minute flight, the Brazilian VSB-30 rocket touched down in the snow of northern Sweden, bringing to an end the world’s first microscopic filming of living cancer cells in a state of weightlessness.

Launched from Sweden’s Esrange Space Centre on 27 April 2015, the rocket took the cancer cells 255 km into space and brought them back again. The experiment has given us new knowledge of what it is that makes cancer cells particularly vulnerable in space.

”This has been a fantastic project,” says assistant professor Thomas Juhl Corydon from Aarhus University.

Together with his colleague, Daniela Grimm from Aarhus University, he has led the international project which has been two and half years in the making.

Laser analysis of the cellular skeleton

On board the spacecraft was a specially built microscope which, by firing a laser beam into the cells, examined how the skeletons of the living cells, their cytoskeletons, change in zero gravity.

”Just as humans have a skeleton of bones, the cells have some proteins and components reminiscent of guy ropes. They keep the cell stretched, but also play an important role in transport within the cell, so they’re also a sort of motorway,” says Corydon.

That is why it was crucial for the scientists to be able to use the new microscope to examine the cytoskeleton purely by illuminating it with laser. The microscope, which Corydon refers to as ’a little miracle of engineering’, was developed at the German space centre DLR (Deutsches Zemtrum für Luft- und Raumfart).

”We genetically modified the cells so that their cytoskeleton lights up green. When you shine light onto the cells you excite the fluorescent protein, just like when you get a stamp on your hand at a nightclub,” says Corydon.

Freezing disrupts the result

The scientists have long suspected that in a weightless state, changes occur in the cytoskeleton which may ultimately cause cancer cells from the thyroid gland to commit suicide.

They have observed this on Earth in what are called random position machines, which constantly alter the orientation of the cells, confusing them so that they no longer know what is up or down. This has a damaging effect on how the cells express their genes.

”We have also looked into which proteins grow or reduce in number, and this suggests that it has something to do the cytoskeleton,” says Corydon.

This is why it is crucial for the scientists to be able to observe the changes in a proper weightless state without inflicting too much damage on the cells. Previously, it was necessary for scientists to freeze and sometimes kill the cells before they were analysed which could damage the results. With the new technology this is no longer necessary.

Reveals cancer’s vulnerability

This is not the first time the scientists have examined cells in a weightless state. In 2014, cancer cells were sent to the International Space Station where they were exposed to zero gravity for ten days before being killed and frozen.

Although the mission only rendered the cells weightless for six minutes, the new technology has given scientists knowledge which could potentially be used in cancer research.

”Here on Earth, the cells behave in a single specific manner and are perhaps unwilling to divulge the secret of what makes a good weapon against cancer. By exposing them to zero gravity it may be possible to identify genes or the products of genes which are much more vulnerable,” says Corydon.

Cancer cell research to be published in journal

He is, however, not yet willing to reveal exactly what the scientists discovered in their new experiment.

”Of course we’re going to publish this in a journal so I can’t really say anything yet, although I can reveal that we did observe changes in the cytoskeleton,” he said.

----------------

Read the original story in Danish on Vidneskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews