Sun can emit superflares every 1000 years

The Sun has the potential to emit massive ‘superflares’ every 1000 years, say scientists.

The Sun regularly, spews out solar flares--violent explosions that hurl enormous amounts of plasma into space, disrupting satellites and causing power failures here on Earth.

But these outbreaks are still small compared with the gigantic eruptions on other stars. These so-called 'superflares' can be up to 10,000 times bigger than the largest solar flares from our own sun.

Now new research suggests that our sun might be capable of forming similarly large superflares every 1000 years, and this could have devastating consequences, says lead-author Christoffer Karoff, from the Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Denmark.

"We know that these electrical particles from the Sun destroy the ozone layer. It’s suggested that the major flares that we know of led to a reduction in the ozone layer of five per cent. But no one really knows what will happen at this [superflare] level,” says Karoff.

The study is published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

Sun can create 'superflares'

British astronomer Richard Carrington, witnessed the largest solar flare ever recorded on Earth in 1859. It damaged telegraph wires and ice cores even suggest that it damaged the ozone layer.

The event was later named the Carrington Storm, and it is an example of how damaging these severe storms can be.

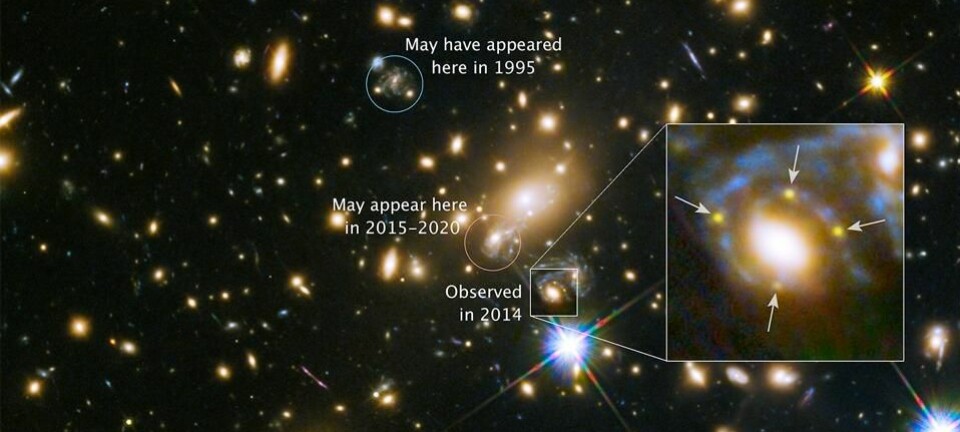

But a study in 2015 suggested that even bigger solar flares have reached Earth in the past. The scientists behind this study found evidence of two massive solar storms in tree rings dating back 1,000 years-at least five times more powerful than any other solar storm on record.

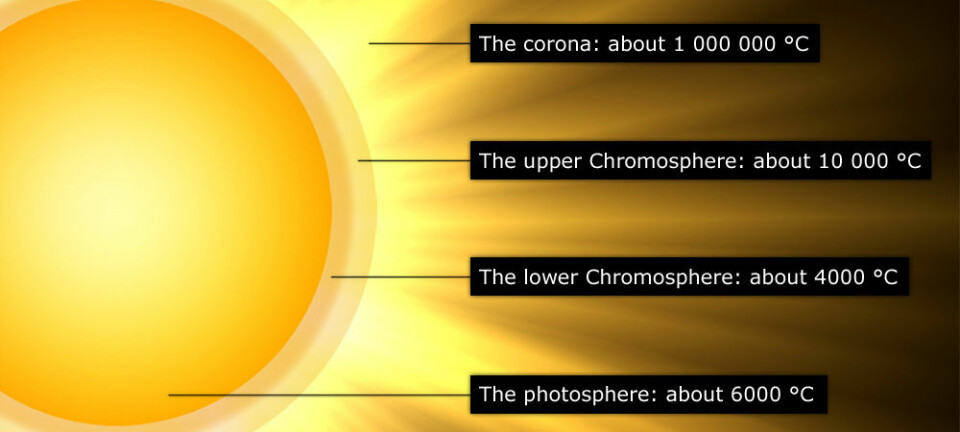

The new study measured the magnetic field of superflare stars out in space. They calculated that the Sun’s magnetic field is indeed capable of producing ‘small’ superflares--100 times the size of a Carrington Storm.

"We definitely hadn’t expected to find superflare stars with equally weak magnetic fields as our own. This means that the Sun could create a superflare and it's a very scary thought," says Karoff.

No one is safe from a large coronal mass ejection

Peter Stauning from the Danish Meteorological Institute is impressed with the new results.

"I think it is a beautiful and very insightful article," says Stauning, who studies space weather but was not involved in the new study. It has implications for understanding solar behavior and the impacts here on Earth.

But what can we expect if such a massive solar flare struck the Earth?

First there would be a blackout of all radio signals, says Stauning. Then satellites would be paralyzed and followed by failure in communications, GPS, and power.

Ozone layer damaged with serious consequences

We have never observed a superflare here on Earth, so scientists do not know exactly what to expect, should one occur. One major consequence could be damage to the ozone layer, says Karoff.

"The ozone layer protects us from ultraviolet radiation from the sun, and we would receive dramatically more radiation and see more cases of skin cancer if it is reduced. But it’s actually a huge unanswered question--what will an increase in radiation mean, here on Earth."

Scientists could examine the two large solar storms identified in the 1,000-year-old tree ring record for more answers, says Karoff.

Greater threat from asteroids and nuclear bombs

Stars with weak magnetic fields, just like our Sun, do not usually create such major superflares. And this suggests that there is likely to be an upper limit to the size of these flares, says Karoff. Statistically, superflares from the Sun occur approximately every 1,000 years, he says. But he emphasises that this estimate cannot be used to predict them.

It’s unlikely that a superflare could strike the Earth anytime soon, says Stauning.

"I don’t think that the probability in this context is very big. Solar flares [are emitted] in all directions, and perhaps only a tenth of the outbreak would hit the Earth,” he says.

But there is a serious risk of another Carrington Storm, say Stauning and Faroff.

"There is a real possibility of another Carrington event and that’s something that power stations for example, must consider."

----------------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex