Cosmic dust change our understanding of the birth of the universe

A new study opens up for entirely new understanding of what the early universe looked like.

Physicists have found cosmic dust in a galaxy that was formed 13.1 billion years ago -- which is only seven million years after Big Bang and the birth of the universe.

The discovery comes as a surprise to the scientists, who had thought that the solid particles which make up the cosmic dust did not come into existence until much later in the history of the universe.

"Dust plays an incredibly important role in the history of the universe because it helped to make planets. But not everyone believed that there would have been time for the early galaxies to have produced dust, since according to certain theories this takes many billions of years. For this reason they were rather surprised to see dust as early as 700 million years after Big Bang," says project leader Darach Watson, and astrophysicist from the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

The discovery, which has been published in Nature, was the result of an international collaboration led by physicists from the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

The discovery has also caused interest among other scientists who see it as an opportunity to better understand the interactions in the early universe.

"This discovery is extremely exciting because it tells us a whole lot about the early phases of the universe," says Professor Jørgen Christensen-Dalsgaard from the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Aarhus University. “All that existed after the Big Bang was gases of hydrogen and helium, so the dust stems from nuclear reactions in stars very early in the history of the universe. We need to take a closer look to see whether the galaxy is typical of its time.”

According to the scientists involved in the project, the discovery shows, among other things, that galaxies as we know them today formed far earlier than previously thought because cosmic dust is a prerequisite for the formation of normal stars, solid planets, and complex molecules -- all of which are vital ingredients for the development of life.

Mystery surrounding cosmic dust

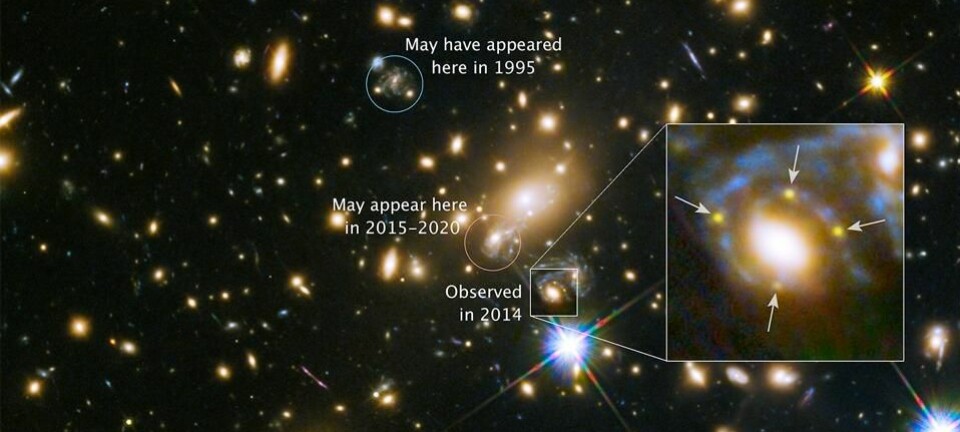

According to assistant professor Watson, the galaxy, which has been given the name A1689-zD1, had previously been discovered by the Hubble telescope and ALMA (the Atacama Large Millimeter Array). At that time, the scientists assumed the galaxy was placed very far away, but were otherwise not able to say anything more about it.

Scientists therefore began to observe the galaxy more closely using instruments located in the Atacama Desert in Chile.

The VLT (Very Large Telescope) was used to measure radiation from the stars in the galaxy and thus to give a more precise distance between the galaxy and Earth. This helped the scientists to date the galaxy: 13.1 billion years.

ALMA was used to observe the infrared light emitted by dust in the galaxy. Information from both the new and previous ALMA observations show, according to the scientists, that the galaxy is full of stars and metals.

Although the discovery is surprising, according to Watson it does not give a definitive answer as to where the dust comes from.

According to Watson a "great mystery still surrounds the origins of cosmic dust" which means that there is still a lot of work to be done if they are to get to the bottom of what the early universe looked like.

Supernovas may hold the answer

The team of scientists at the Niels Bohr Institute are now trying to get closer to understanding what could have created the cosmic dust such a short time after Big Bang.

"Astronomers have always believed that dust had its origins in old stars after a process that took billions of years -- but as it turns out this theory is mistaken. We simply need a theory that describe how dust is made in such a short period of time," says Watson.

A process which in theory could produce dust quickly enough could, according to Watson, would be that in the heart of a very big supernova. But that theory also comes with some complications.

"For supernovas to form all the cosmic dust we are measuring would demand an efficiency of between 50 to 100 per cent. The problem is just that supernovas also help to destroy the dust immediately after it’s emitted," says Watson.

According to the scientist, the answer may well lie in that supernovas in the early universe behaved very differently than the supernovas we observe today.

--------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews