Newly discovered planetary system alters our view of planet formation

New data from NASA’s Kepler mission has revealed what was thought to be difficult: a planetary system that orbits around two stars. We need to modify our theories, says Danish astronomer.

Almost a year ago, scientists discovered a planet which totally changed our view of planet formation.

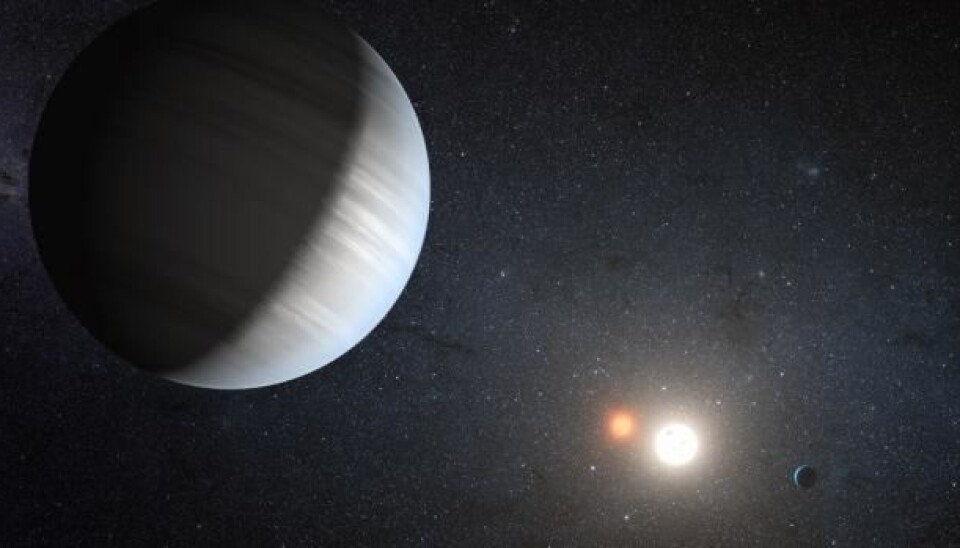

The planet orbited not just one but two stars.

And now they have done it again: data from the Kepler space observatory has revealed two planets – which can be classified as a planetary system – that also orbit two stars.

“This is an important discovery because it shows that close binary stars can host complete planetary systems,” says post doc Lars A. Buchhave, of the Niels Bohr Institute and the Centre for Star and Planet Formation at Copenhagen University, who is part of the international research team behind the discovery.

“Up to a year ago it was believed that it was difficult to form planets in binary star systems. But our discovery of these planets orbiting binary stars tells us that this is not so.”

The discovery of the new planetary system, which has been named ‘Kepler-47’, has been published in the journal Science.

Existing theories are incomplete

Formation theories have long been based on the notion that planets always orbit a single star. It’s been assumed that planetary systems with multiple stars give rise to unstable planetary orbits, which could result in the formation of the planets being disrupted.

It was also believed that two or more stars moving around each other would cause such chaos in the surrounding gases – which according to existing formation theories need to merge into a disk in order to form a planet – that planet formation would be difficult.

Discoveries like this are important to science because without them we couldn’t come up with theories that have a basis in reality. This is how we spot the shortcomings of existing theories.

But this turned out not to be the case. The scientists found that it’s perfectly possible for a single small planet to be formed around a pair of stars. But that was as far as it could go – they thought.

Until now. the Kepler team has discovered not just one, but two planets orbiting not just one, but two stars.

”Discoveries like this are important to science because without them we couldn’t come up with theories that have a basis in reality,” says Buchhave. “This is how we spot the shortcomings of existing theories.”

Similar to Earth’s orbit

The planets in the newly discovered planetary system have radii 3.0 and 4.6 times that of Earth, respectively. Their orbital periods are 49.5 and 303.2 days, respectively.

The 303.2-day orbital period is interesting in itself as it comes close to our own orbital period of 365 days.

This basically means that the outer planet is about as far away from its host stars as Earth is from the Sun. And this, in turn, means that it resides within what scientists call ‘the habitable zone’.

And had it not been for the fact that the outer planet is a gas planet, this would be pretty big news. It would mean that, technically, the planet could contain liquid water – one of the main prerequisites for life.

“It’s not all that interesting in relation to this particular planet since it’s a gas planet, and so we won’t find any life there – or at least not life as we know it” says the Danish astronomer.

“But it nevertheless shows us that a planet in such a system can reside in the habitable zone.”

Tiny changes in brightness led to the jackpot

The newly discovered planetary system is part of the constellation Cygnus, which is located some 5,000 light years from Earth.

So how do scientists manage to find something as distant as that? The answer lies in the brightness of the stars.

When one of the planets passes in front of the host star – when viewed from Earth – it results in a miniscule dip in the star’s brightness. The change in brightness is too tiny to be detected with the naked eyes, or by most other satellites for that matter.

But this just happens to be one of Kepler’s strongest features. The satellite constantly measures miniscule dips in the brightness of 155,000 stars. These changes can for instance reveal when a planet passes in front of or ‘transits’ its host star.

Plenty of new discoveries

Since the Kepler mission started three-and-a-half years ago, there has been a seemingly endless stream of new discoveries. Some have been substantial, while others have drowned a bit in the crowd.

With the constant stream of discoveries from the satellite, it can be a bit difficult to relate to them all, he says:

“All this data has overwhelmed us a bit. This certainly is an exciting step, but it’s not as big as when we last year discovered a planet that orbited around two stars.”

Kepler 16b, which is what they called the planet they found a year ago, was a big discovery because it was the first ever example of a planet forming around two stars. With this discovery it became clear that there may be several planetary systems different from our own just waiting to be discovered.

“The discovery of Kepler-16b showed that planets can be formed around binary star systems. Since then we have discovered more systems like this, which indicates that such systems may actually be quite common,” says Buchhave.

“The discovery of Kepler-16b also showed that binary stars can not only house single planets, but planetary systems too.”

----------------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther