Researchers have discovered that there’s something not quite right with Norway's finest Baroque art from the 17th century

For a long time, the wrong person has been given the credit for much of the art.

In the Norwegian city Stavanger, people are proud of the medieval cathedral in the middle of the city centre. Not to mention the beautiful 17th century art the church can offer inside – perhaps the finest Baroque art in Norway.

The Stavanger Cathedral is currently under renovation, so all the art has been taken down.

The inventory was carefully examined by painting conservators and other experts.

They have discovered that something is not quite right.

Was Anders Lauritsen Smith the artist?

In Stavanger, people have long been told that it is the local artist Andrew Smith who is behind both the pulpit and the epitaphs in the Cathedral. Smith was a Scotsman who took the Norwegian name Anders Lauritsen Smith.

The pulpit in Stavanger is perhaps the finest example of Baroque art from the second half of the 17th century in Norway.

The epitaphs with the paintings of people from Stavanger from many hundreds of years ago usually hang high up on the church wall. They are impressive when you get to see them up close, just like sciencenorway.no had the opportunity to do in the studio of the Archaeological Museum at the University of Stavanger.

The artist has been honoured with his own ‘Andrew Smiths gate’ (Andrew Smith’s street) in Stavanger.

However, the research group that are examining the church art warn both the people of Stavanger and art historians that they should prepare for a surprise.

A bit scary

“It almost feels a little scary. What if we can now prove that it is an artist other than Anders Smith who was behind much of the most famous art in Stavanger Cathedral,” painting conservator Anne Ytterdal says.

The research project Stavanger's baroque inventory under the microscope - who carved and who painted? is a collaboration between Stavanger Museum and the city's Archaeological Museum.

It came about in connection with the city of Stavanger and the Cathedral’s upcoming 900th anniversary in 2025. To prepare for this, all the interior is being thoroughly restored. In the museum's atelier, Anne Ytterdal collaborates with her colleagues Hilde Smedstad Moore and Lise Chantrier Aasen – all painting conservators.

Joining the team is furniture maker Michael Heng from Stavanger Museum. He has been working on the history of the wood carvings in Stavanger Cathedral since 2004. The retired state archivist and historian Hans Eyvind Næss is also involved. He is looking through documents from the 17th century.

The oldest Norwegian Cathedral

Stavanger Cathedral was built in the first part of the 12th century and is the oldest of Norwegian cathedrals still standing. The building is also the one that has retained most of its original medieval appearance.

Following the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, Stavanger Cathedral fell into disrepair, according to the city's bishop at the time. He complained of his distress in a letter to the king in Copenhagen.

But the 17th century brought economic prosperity to Stavanger. Wealthy locals who could contribute to not only the restoration of the church, but also beautiful decorations emerged.

Most important for the new Baroque art in the Cathedral was the artist Anders Smith.

At least that's how it's been told for a long time.

In the 1920s, there were several Norwegian art historians who wrote a lot about Baroque. Anders Smith is central to all of them.

The author Kjartan Fløgstad has also been fascinated by this. He has written the chapter on Anders Smith in the Norwegian biographical encyclopedia (link in Norwegian) and uses Smith’s 17th century setting in his prizewinning novel Kron og mynt from 1998.

Changing the story of Anders Smith

Both in Stavanger’s history and Norwegian art history, Anders Lauritsen Smith is described as influential.

A wonderful artist and a man of high social status in his time. He must have lived on a large estate in Sola.

Hans Eyvind Næss and Michael Heng's investigations now indicate that this is completely wrong.

“He first lived in a small house in Stavanger, a place where few or none of the bourgeoisie lived. Later, he married and moved to Sola,” Næss tells Stavanger Aftenblad (link in Norwegian). “When he died, he lived on a small, simple farm which was not worth much. We also know from the certificate of probate following his death that he did not own much. There were some simple farm implements, a spinning wheel and various other things. Of livestock, there was an old cow, a heifer, an old horse and three sheep.”

A certificate of probate gives inheritors control over the estate of someone who has died.

A completely different person

Influential? Not at all, the historian concludes after his search in the city's old archives.

Much now indicates that it was a completely different painter than Anders Smith who was very active in Stavanger at the time.

“We also believe that it may have been someone completely different from Anders Smith who carved the pulpit in the cathedral,” Hilde Smedstad Moore tells sciencenorway.no.

Something wasn't quite right

Michael Heng, Eyvind Næss and the three painting conservators have suspected that something wasn’t quite right with the story Stavanger people have been told year after year for a while.

“That Anders Smith is supposed to have been both a sculptor and a painter, among other things, does not agree with the guild standards and practices we see that creaftsmen adhered to in the 17th century," Næss says.

There were strict boundaries between the various guilds. Hardly any of the craftsmen of the time crossed these borders.

Smith is mentioned as a painter in a letter from 1682. But Eyvind Næss finds no trace of him as a sculptor in the city's archives from the 17th century.

That makes it unlikely that he is the one behind the pulpit in Stavanger – which is considered to be Norway’s finest example of Baroque art.

The guild boundaries were followed

“ We know that people could be chased from Stavanger in the 17th century if they engaged in craft activities that they did not have permission to carry out. The guild standards were followed,” Moore says. “So the people of Stavanger have been told that Anders Smith has both carved and painted the pulpit and the framework of the epitaphs, and is also the artist behind the family portraits in the Cathedral. But we simply cannot see how that could be possible.”

The epitaphs in the Cathedral

An epitaph is a commemorative image of deceased people.

Five of these hang on the walls of Stavanger Cathedral.

There are several epitaphs in Norwegian churches, but those in Stavanger are perhaps the most famous.

Most epitaphs in Norwegian churches are from the 17th and 18th centuries. They are often in memory of bishops and priests or more worldly nobles, civil servants, and merchants. The wife and children are often included in the epitaphs. A skull or Jesus on the cross may also be included.

The epitaphs were made by the most skilled painters and craftsmen of the time.

They maintain a high artistic quality, as the Baroque furnishings from Stavanger Cathedral testify.

X-ray, UV light and pigment analysis

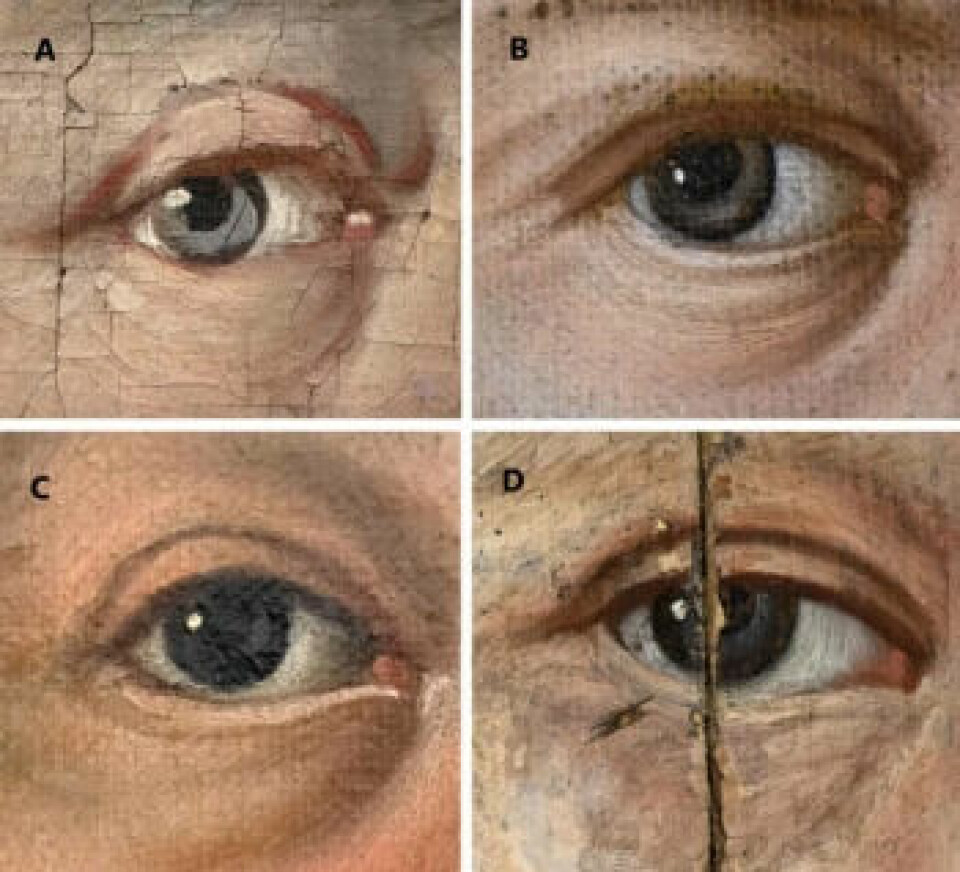

“With today's analysis tools, we have a completely different opportunity than before to research paintings like this. We can go all the way down to the microscopic level,” Moore tells sciencenorway.no.

Analyses of the pigments that have been used and how each individual artist constructed their painting can tell us a lot.

“We are also investigating how details such as hands and eyes are painted differently. It can put us on the trail of an artist's distinctive features,” Moore says.

The Kielland family and the artistic genius

In the 1920s there was a lot of interest in art in Stavanger Cathedral.

A hundred years ago, the Norwegian art historians of the time with surnames such as Grevenor, Platou and Schnitler established a lot of information that has later been considered to be correct. We have, quite frankly, accepted it at face value.

Few have followed the old Norwegian art historians more closely.

In Anders Smith's case, it was perhaps also important that he was related to a branch of the well-known Kielland family in Stavanger.

The Kielland family has played a significant role in Stavanger's history. Writing an artistic genius into the story of the family may have suited some.

Or maybe it just happened without any conscious thought behind it.

A man named Peiter

Now that the researchers in Stavanger have found no trace of Anders Smith being a wood carver and can therefore most likely rule out that he is the one who made the pulpit in the Cathedral, and that he may not be the artist behind the wonderful epitaphs either – who was the one who actually painted and carved the Baroque art in the Cathedral?

In Stavanger's old archives, the furniture maker and the retired state archivist have found clues.

They point to a man called Peiter Billedhugger (Sculptor).

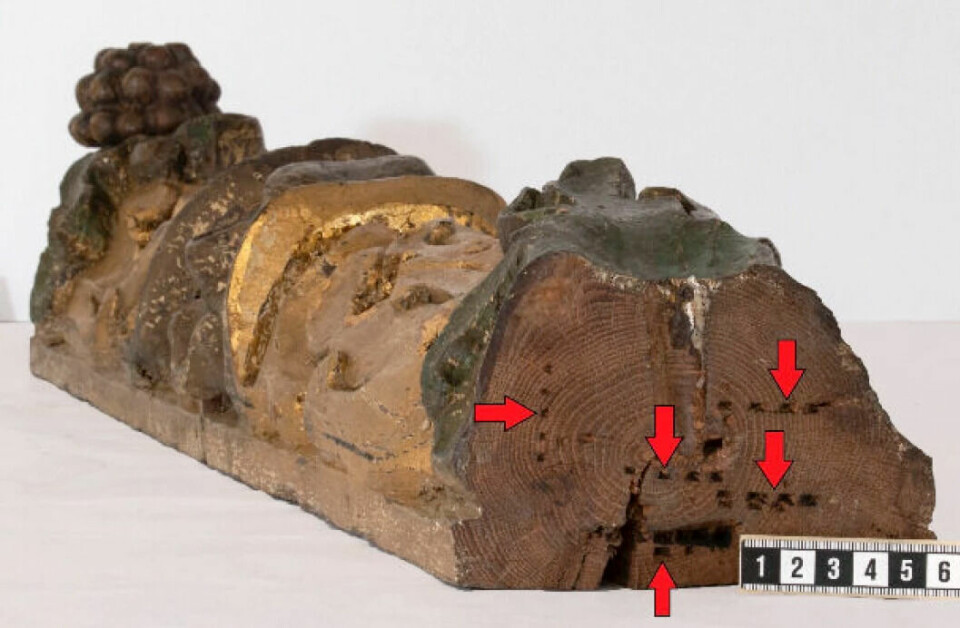

They can follow Peiter from the time he was a qualified journeyman in 1627 until he received citizenship in Stavanger in 1657. There are also sources pointing to Peiter being a sculptor in Kinn, Førde, Bergen and several other places in Western Norway. Tool marks have also been found which link the clues to the Baroque inventory in Stavanger Cathedral.

The years Peiter worked in Stavanger match. The researchers also find striking similarities in the art he may be behind, including the pulpit in the Cathedral.

“Everything indicates that he is our man,” Michael Heng tells Stavanger Aftenblad.

New investigations into old archives also tell of a Daniel Maler (Painter) who became a citizen of Stavanger in 1657. The researchers believe they can already demonstrate that more than one person painted the family portraits in the Cathedral.

Daniel Maler is a name that has come up. He may be one of the painters.

How can the artists be mistaken?

In the National Museum in Oslo and also several museums and churches in Western Norway, there is art for which Anders Smith has received credit.

“We now probably have to rewrite this part of Norwegian art history,” Anne Ytterdal tells sciencenorway.no.

Her colleagues Hilde Smedstad Moore and Lise Chantrier Aasen have so far written an article in the journal Norske Konserves (link in Norwegian), where they write a little about the detective work in Stavanger.

Here, the two researchers point out that when a work of art lacks a signature, ‘truths’ relating to some of the better-known artists of the time easily arise.

Often, art historians give the credit for works of art of unknown origin to artists that are already well known. Certain distinctive features and details are highlighted as ‘evidence’ for the well-known artist in question.

Later, writers continue to tell the exact same story. They simply follow in the footsteps of the person or people who first ‘discovered’ something.

Older literature is used again and again as a source. This is how researchers and others maintain the misinterpretations.

“Our work with this material from Stavanger Cathedral shows how important it is to seek new information that can either substantiate or refute established truths,” the conservators in Stavanger tell sciencenorway.no.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

L.C. Aasen and H.S. Moore. ‘Stavanger domkirkes barokke inventar under lupen: Hvem har skåret og hvem har malt?’ (Stavanger Cathedral's Baroque inventory under the microscope: Who has carved and who has painted?), Norske Konserves, 2001/2.