When will the Arctic be ice free?

Sea ice is declining rapidly and the prospect of an ice-free Arctic is drawing ever closer. But when will it happen? We cut through the headlines to bring you the facts.

The Arctic is now heading into winter after another record-breaking summer. And there has been no shortage of dramatic headlines.

Reports have flooded in of record-breaking warm temperatures in Greenland, both on land and at sea, and near record low summer sea ice. The prospect of an ice free Arctic during the summer now seems inevitable, but when?

Most scientists agree it will happen sometime this century, but have roundly criticised the most recent claims by British scientist, Professor Peter Wadhams in the Guardian newspaper that the Arctic is likely to become ‘ice-free’ as early as next year.

So as we say goodbye to the Arctic summer for another year, it is time to take stock. ScienceNordic cuts straight to point and brings you the facts.

True: Sea ice extent second lowest on record

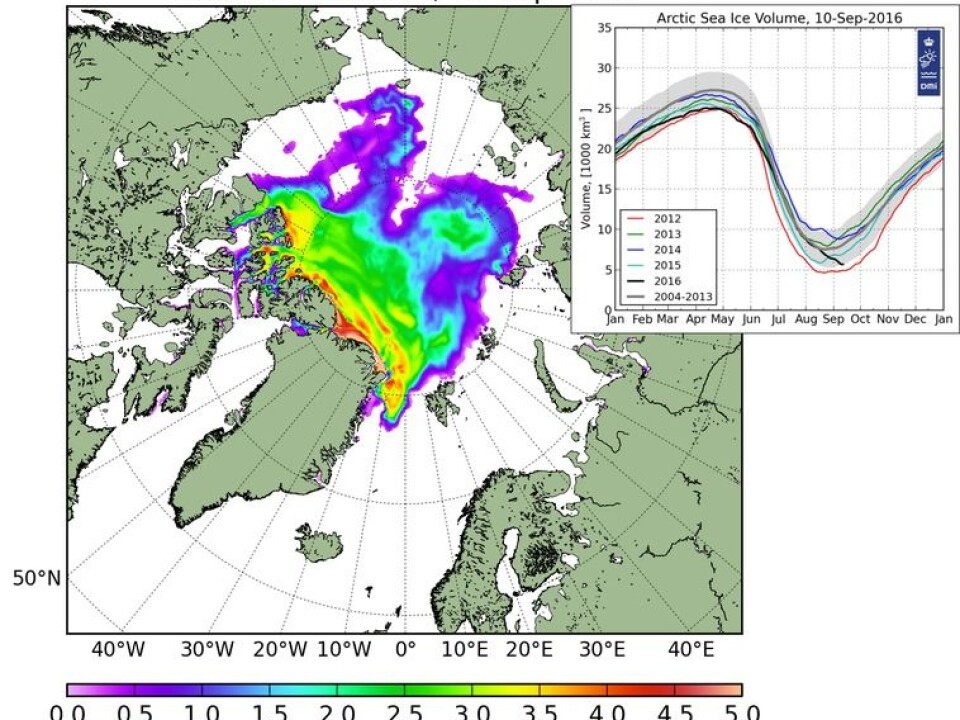

The National Snow and Ice Data Center in the US reported that summer sea ice reached its minimum extent on September 10 this year, clocking in at 4.14 million square kilometres. This places it joint second with 2007 for the lowest summer sea ice minimum on record. The lowest occurred in 2012.

“On September 10, it was 4.14 million square kilometres. That is 0.01 million square kilometres less than 2007 (statistically insignificant) and 0.75 million square kilometres more than 2012,” says Martin Stendel, from the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI), who are currently preparing their annual report on the Arctic.

This compares with the long-term average of 6.70 million square kilometres recorded between 1979 and 2010, and represents yet another year of declining sea ice since satellite records began in 1979.

All ten of the lowest Arctic sea ice extent minima have occurred in the last 11 years.

These data only relate to the summer, when Arctic sea ice is at a minimum. On the other side of the scale is winter maximum extent, which is also in decline.

Daily Arctic sea ice volume animation using data from the 1979 to present day PIOMAS reconstruction. Sea ice loss produces the inward spiral. (Credit: Ed Hawkins, National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS) at the University of Reading, UK)

True: So-called ‘last ice’ also in decline

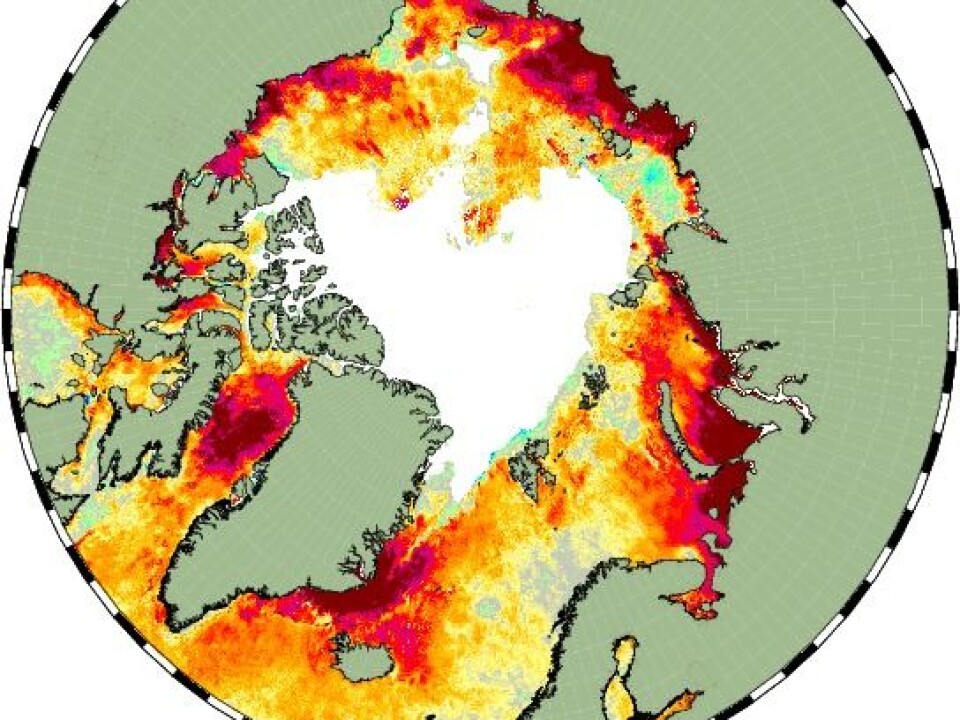

Sea ice thickness is also on a downward spiral.

"Broadly speaking you can look at sea ice thickness to figure out how old the ice is, if the ice is more than a metre thick it has most likey survived at least one year in the Arctic. Sea ice with many metres thickness is known as multi-year sea ice as it has been through several melt and freeze seasons,” says Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist with DMI.

According to DMI’s models of sea ice thickness, only a narrow strip of ice older than three or four years has survived this year’s summer melt season.

“The oldest sea ice is around the North coast of Greenland and Arctic Canada, and that’s four or five years old. This is sometimes called the ‘last ice’, as this is probably the last place where there will be permanent year-round sea ice in the Arctic,” says Mottram.

“What we see, and what some of my colleagues are concerned about, is that it looks like there is a lot of multi-year sea ice that has been piled up and it’s being pushed through the Fram Strait and out of the Arctic. So when the melt season starts again next year, a lot of the multi-year sea ice will have gone,” she says.

The ice left behind is younger, typically less than two years old, and thinner. This makes it more vulnerable to rapid melt during the summer and makes it less likely that sea ice will recover the following year.

Read More: Arctic sea ice at a record low

True: Both man-made climate change and natural variability to blame

It is no secret that the Earth is warming due to man-made climate change, but this warming is most dramatic in the Arctic--a process known as Arctic amplification (see fact box).

On top of this long-term climate trend, local weather also played a role in this years declining sea ice. Greenland experienced exceptionally warm temperatures on land, and more crucially, in the ocean towards the end of the melt season, which accelerated ice melt late in the season.

“The atmosphere has been warm, but the ocean has also been especially warm. Pretty much anything not covered by ice was three or four degrees above what we’d expect for this time of year. And this warm water in the Arctic Ocean is partly what’s been driving this ice loss,” says Mottram.

On top of this, two natural climate patterns were caught in a tug of war. The strong El Nino, which contributed to record breaking global temperatures in 2015 and 2016 has now ended. But in its place another pattern appeared--the so-called Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO).

The PDO entered into what is known as a positive phase, which means that warm water from the Pacific Ocean is pumped into the Arctic.

Read More: Human-induced global warming began 180 years ago

Likely True: Arctic will be ice free this century

To sum up, an ice-free Arctic summer will most likely become a reality sometime this century.

“I would say the loss of nearly all Arctic sea ice in late summer is inevitable provided that atmospheric CO2 (and other greenhouse gasses) continues to rise and CO2 is not somehow brought down below 400 ppm,” says Professor Jason Box, a glaciologist with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS).

But few scientists are willing to venture a guess as to exactly when the Arctic could pass this summer ice threshold.

“The Arctic will be considered “ice free” when sea ice covers less than one million square kilometres. That’s using the 30 percent cut off for sea ice cover,” says Mottram. But this low needs to persist for five years or more in a row, before the Arctic will be considered permanently ice free, she says.

“Based on model projections it might happen by the middle of this century, but it could be the end of the century. It’s very difficult to say. We might pass the threshold accidentally next year, or the year after, but then it could be 10 years or 20 years before it happens again,” says Mottram.

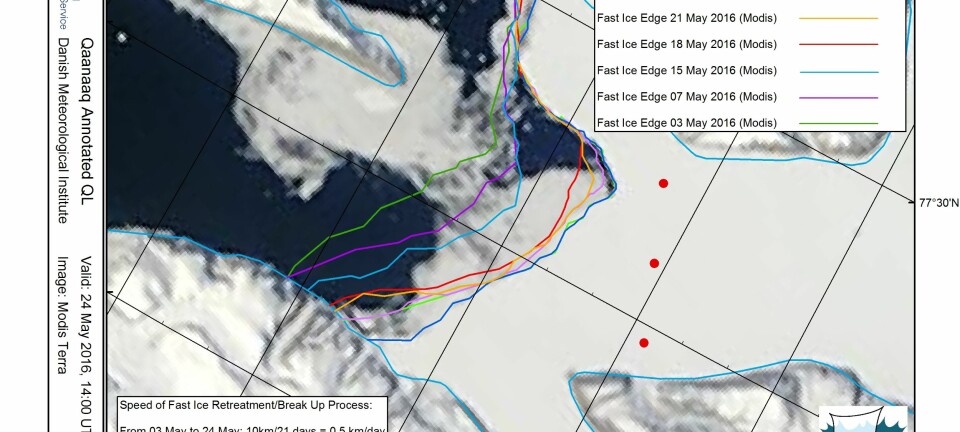

Her colleague, Steffen Olsen agrees. Olsen is an oceanographer with DMI and monitors sea ice thickness in north west Greenland with the help of local hunters.

“Generally speaking, we don’t expect to see an ice free Arctic happening in the next couple of years. But there is uncertainty. Model predictions are wide-spread, but we see that in the middle of the century we may experience ice free conditions in summer. Meaning that you will be able to navigate across the Arctic Ocean,” says Olsen.

Read More: Greenland melt linked to weird weather in Europe and USA

Why do scientists disagree?

The spread in model predictions makes it almost impossible for scientists to narrow down a precise year or even decade for when the Arctic could pass the ice-free threshold.

Even predicting one year in advance is hampered by the unpredictability of local weather and ocean temperatures which drive sea ice melt.

Much of it will depend on future temperature trends, which depend on future greenhouse gas emissions. But there are also a number of unknowns that are difficult to include in climate models, says Olsen.

For example, future cloud cover in the Arctic is difficult to predict as are possible dramatic events such as a slow down in ocean circulation in the Atlantic that brings warm water to the Arctic. These types of dramatic events are not included in climate models and are difficult to assess in a warming world.

“We can’t say what will happen next year, but it’s at a sensitive point right now and we can only hope that the next winter will be severe and calm so that the ice can grow and thicken over a larger part of the ice,” says Olsen.

Read More: Climate models underestimate rapid ice melt events on Greenland

What are the impacts of declining sea ice?

The record low sea ice extent and thickness are already having an effect for the people and animals that depend on the ice and shocking scientists who study it.

A new study in the scientific journal Crysphere reported last week that in all 19 known polar bear habitats, the sea ice season is now seven weeks shorter, causing problems for the bears who depend on the ice to hunt their food.

Olsen has experienced first hand the increasing difficulty that local Inuit experience when trying to travel across thin ice in summer, and the increased danger of doing it during the long dark Polar winter where spotting soft, thin ice is particularly difficult.

“They are nervous. They have a way of living, but it’s changing, and it’s hard to see how this will go,” says Olsen.

“They do see some positive aspects, where they can sail for longer periods of the year. But we don’t know how fishing or hunting will develop as we can’t be sure that the ecosystem will respond positively,” he says.

Scientific links

- The National Snow and Ice Data Center report on summer sea ice, 2016

- The Sea Ice Outlook report

- Polar Portal (Sea Ice Data)

- Sea-ice indicators of polar bear habitat. DOI 10.5194/tc-10-2027-2016