Archaeologists reveal new finds from legendary Swedish warship

The Mars warship was carrying hundreds of soldiers when it exploded in the Baltic Sea in 1564 during the Northern Seven Years’ War.

Cannons, hand grenades, and up to a thousand soldiers were on board the large Swedish warship when it exploded in the Baltic Sea, 454 years ago.

The ship, known as Mars, belonged to the Swedish navy and was one of Northern Europe’s largest and most feared naval vessels used in the Northern Seven Years’ War.

The remains were discovered at the bottom of the Baltic Sea in 2011, near to the Swedish island of Öland.

The latest discoveries from the wreckage were revealed during a press conference in Öland.

“This year, we have come closer to the people aboard. We found more skeletal parts, including a femur with trauma around the knee which we believe to stem from a sharp-edged weapon,” says maritime archaeologist Rolf Fabricius Warming, who is one of the researchers involved in the investigation.

“We also found large guns and a hand grenade. We can see from the wreckage that it was a very intense and tough battle. Between 800 and 1,000 men were on board. That is comparable to the population of an entire medium-sized town at the time. Most of them died in the explosion or when the ship sank into the watery depths,” he says.

Read More: Researchers discover remains of sunken Swedish warship

The ship contained silver treasure

Researchers had previously discovered silver treasure among the Mars wreckage. This time, one of the most spectacular finds was a large grapnel (grappling hook) an anchor-like hook, which hung from the bowsprits of warships and was used to cling onto another ships in order to board it.

Grapnels are illustrated in historical sources from the 16th century, but no actual surviving examples are known apart from this particular one, says Warming.

“It’s totally unique. Together with other exciting finds, it can shed new light on Medieval and Early Modern naval warfare. ,” he says, and adds that the divers also found remains of possible arms and armour, including helmets and swords.

Read More: The Viking’s grave and the sunken ship

Danish and Lübeckian soldiers were on board

Mars sunk due to a gunpowder explosion at the front of the ship. But shortly before, it had been under attack by Danish and Lübeckian warships according to written sources.

“Soldiers fought with hand grenades, lances, and spears, which they threw down from the masts. The fighting was structured and carefully calculated but an absolute ruckus” says Warming.

Danish soldiers, allied with soldiers from Lübeck, managed to defeat the Swedish crew and capture the warship. When the ship exploded and sank, it had three to four hundred Dano-Lübeckian soldiers aboard.

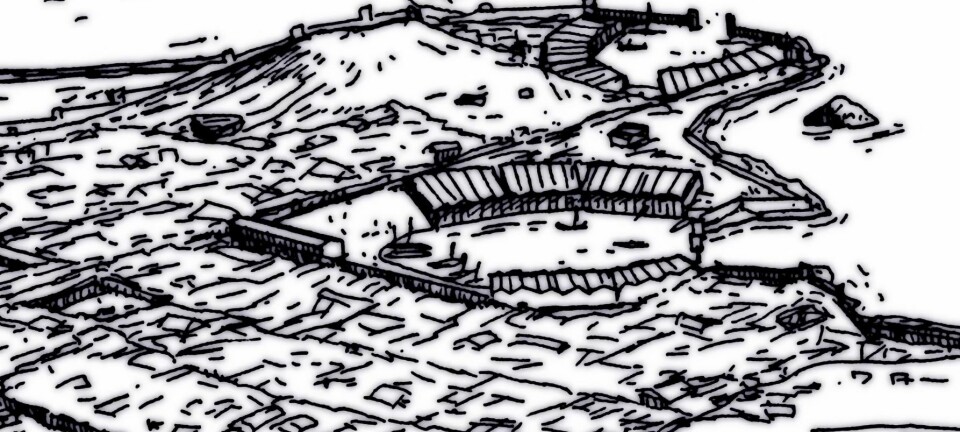

A 3D- model of the shipwreck. (Video: Ocean Discovery / Ingemar Lundgren)

A Swedish change of tactics

The new examination of the Mars shipwreck provides new insights into the events that took place between Denmark and Sweden during the Northern Seven Years’ War between 1563 and 1570.

They have documented a change in Swedish tactics from a focus on close quarter combat to long distance fighting, as indicated by large cannons up to 4.8 metres long.

Despite the large cannons, the Swedish crew did not manage to avoid engaging in close quarter combat with their enemies. The soldiers aboard were positioned underneath a net that covered the deck and was designed to prevent the enemy from jumping on board – a so-called anti-boarding net.

“We know about the use of anti-boarding nets in this battle from richly detailed written sources. The Swedish Admiral, Jacob Bagge, describes in his own account of the battle how he was injured in the shoulder by a javelin thrown from one of the fighting tops of the enemy ships. t. We are told he became furious and began shooting at those who had injured him with arquebuses so that they fell into the net below,” says Warming.

Read More: Medieval shipwreck hints at psychological warfare

A snapshot of a moment in time

Until 2011, historians relied on written sources for information about what happened to Mars, including letters from the Danish admiral Herluf Trolle and the Swedish admiral Jacob Bagge, and official royal documents.

But the shipwreck provides an entirely different type of documentation.

“There’s some ‘fake news’ in the written sources. Many people wanted to claim the honour of defeating the Mars for various political reasons. But when we study the wreckage itself we see a large congruency between the wreck site and the historical sources. One of the most striking observations was that it really was sunk by a large explosion. It was so violent that the front of the ship lies 40 metres away from the other remains,” says Warming.

For maritime archaeologist Mikkel Thomsen from the Viking Ship Museum, Denmark, looking at the well preserved, and complete remains captures a snapshot of a moment in time.

“You really feel that you’re in the killing fields,” says Thomsen, who was not involved in the study.

“The wreckage gives a snapshot of a piece of military and political history. It’s also an international history as the Seven Years’ War was fought across national boundaries,” he says.

Read More: Historic shipwrecks could be preserved in the Antarctic

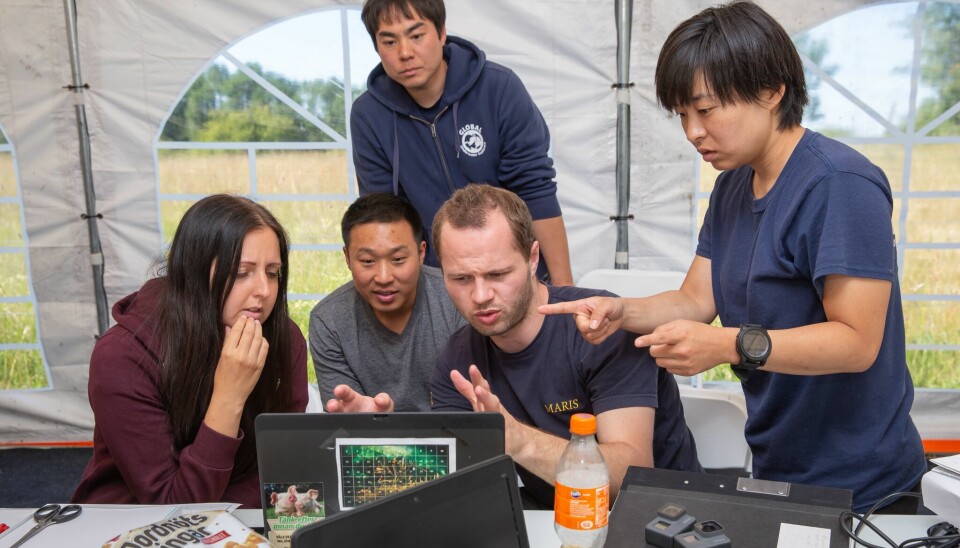

Divers filmed the shipwreck

The Mars remains lay 70 metres beneath the surface of the Baltic Sea—so deep that researchers could not go down themselves to investigate. Instead, professional divers and ROVs were deployed to film the wreck.

The footage and recordings were used to create 3D-models of the wreck and the artefacts found on the site.

Scientists and divers have not been granted permission to touch or remove anything from the wreck or nearby, which might be for the best, according to Thomsen.

“The Baltic Sea has extremely good preservation conditions. The water is low in oxygen, cold, and fresh. So boring worms that are usually the greatest threat to wood cannot live there,” says Thomsen.

Lifting the remains out of the water would lead to breakdown and damage of the materials, he says.

“Moreover, it would be very difficult and extremely expensive to retrieve it from such deep water,” says Thomsen.

The exploration of Mars was carried out by researchers from the Marine Research Institute MARIS at Södertörn University in Sweden, and divers from the diving organization GUE, Västervik Museum, Ocean Discovery, and MMT.

Fifteen divers and ten researchers have participated in the latest exploration of the ship.

---------------

Read the original article in Danish at Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex