See inside three Egyptian mummies

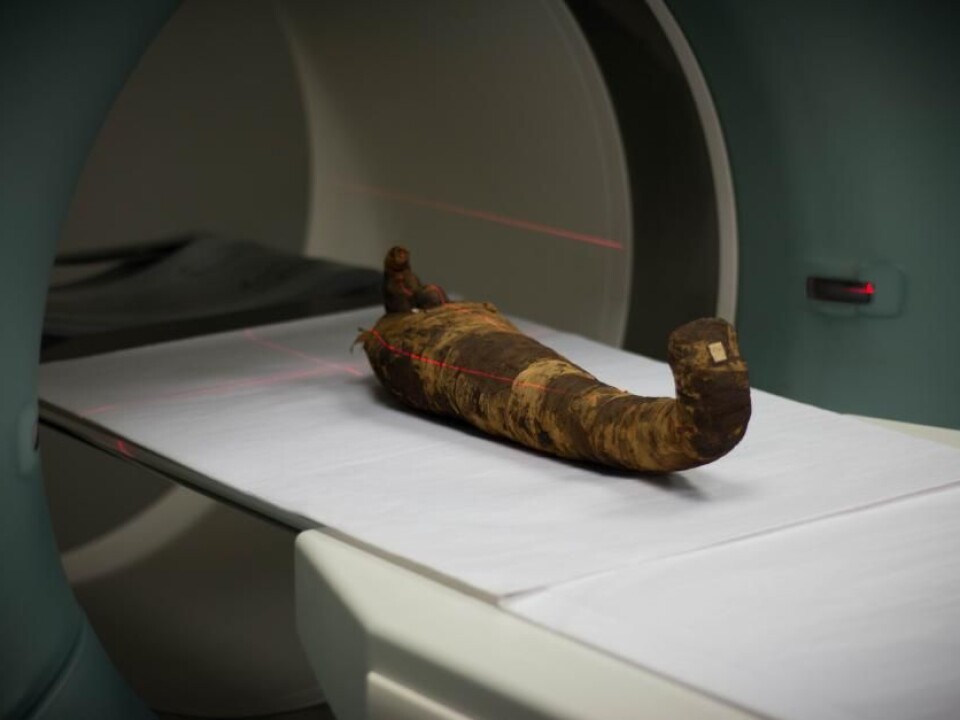

Scientists have scanned three mummies from the National Museum of Denmark for the first time. ScienceNordic was there to see the first results come in.

For the first time ever, the National Museum of Denmark has had the opportunity to scan three Egyptian mummies from their collection.

The mummies were scanned last week at the Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

CT-scanning can reveal details that are impossible to see from the outside. Such as the sex, age, or signs of disease on the mummified body. The scans provide the first glimpses inside two of the three mummies. One of the mummies had previously been x-rayed, but the CT-scans reveal the mummy’s contents in much more detail.

You can see the mummies being scanned in the video above, and see the mummies in more detail in the photos throughout this article.

A child mummy

Scientists already knew that one of the mummies contained a child’s skeleton, as indicated by x-rays. But a CT-scan of the 88 centimetre-long mummy has revealed new details.

The child lay with its arms crossed, the upper part of the body had been crushed, and the brain had been removed during the embalming process, which was a normal thing to do.

“Maybe this practice is related to the amount of time that passes between the time of death and when the embalming is completed. During the embalming process, you remove all the internal organs, liquid and anything that can decay, so depending on how much time has passed… The Greek historian Herodotus tells us that it took the Egyptians about 70 days,” says Egyptologist and museum curator, Anne Haslund Hansen from the National Museum of Denmark.

Previously studied, but by who?

The scans also indicate that someone has tried to open up the back of the mummy to examine it. The scientists believe that this could have been when the upper body was crushed.

The mummy was also patched up at some point, with beige fabric strips held in place with string and glue visible on the outside. These are not typical of Egyptian fabric says Haslund Hansen.

“The question that arises now is how much of this mummy and its outer decoration is in fact a reconstruction. Earlier studies of mummies were rather rough,” says Hansen.

Child’s forehead exposed

During the scan, post-doc Marie Louise Jørkov from the Anthropological Laboratory noticed that the child’s adult teeth had not yet come through. Further analysis will reveal the precise age for the child, she explains.

In general, the teeth are a reliable way of estimating an individual’s age, especially if you compare it with bone development, says Jørkov.

At this point in the scan, the scientists also noticed that a part of the child’s cranium was in fact exposed, and allowed them to see the child’s eye socket.

Not painted by a great artist

Jørkov tried to get a closer look inside the eye socket with the help of a dental mirror and the light from her mobile phone. She was looking for signs of, for example, vitamin deficiency, which was a common cause of death of children at this time.

Unfortunately, she could not see anything as it looked as though the liquid resin-like substance that the mummy had been covered in had dripped down into the hole, obscuring the contents from view.

Meanwhile, Hansen explains the decorations on the outside of the mummy. It is clear that they were not painted by a highly skilled artist, she says.

“I can see these two falcon heads look a little funny,” she says and points at the upper part of the mummy’s decoration. “But in general, I can see that the decorations look fairly Egyptian, even though some parts have been re-patched and re-drawn.”

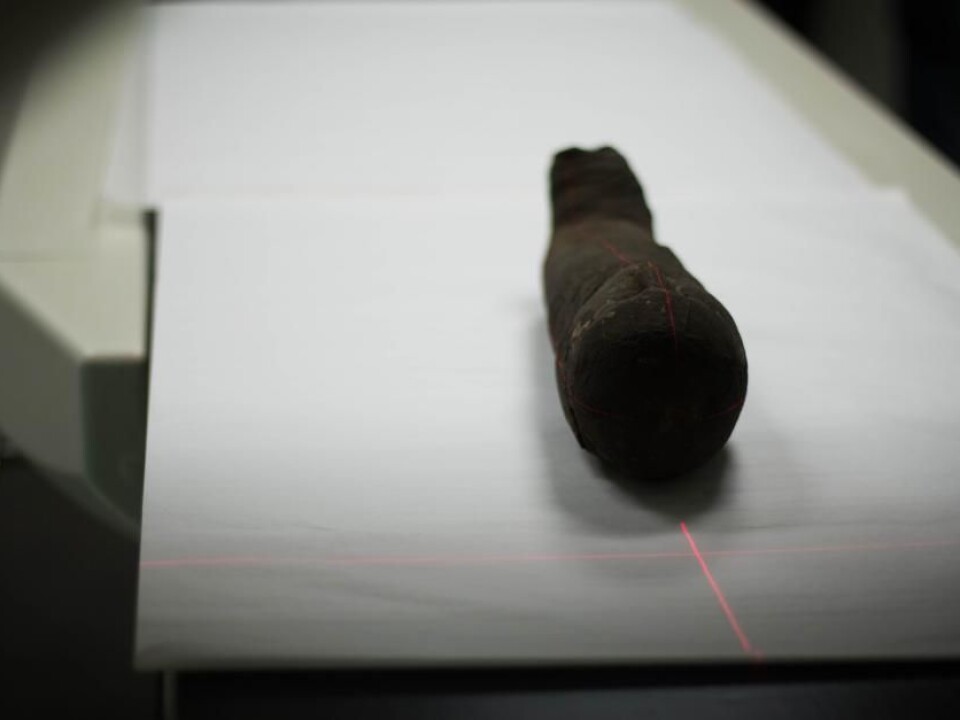

An Ibis Bird mummy that is not all there

Next to go through the scanner is an Ibis bird, about 47 centimetres long. The scans revealed that the top was a complete fabrication and that the lower part was in fact empty. But in between, they saw two bones in the middle part of the mummy and what looked like bone fragments.

With the help of Google, Jørkov identified the bones as a wing belonging to a large bird. It is likely that they come from an Ibis bird.

Bird mummies often contained parts of birds, rather than a whole bird, says Haslund Hansen.

“You should probably view it as a symbolic gesture. We used to think that it was cheating, but perhaps we should re-evaluate that view as we’ve since discovered that it was very common,” she says.

The new-born mummy was empty

From the outside, the last child mummy resembles a new-born baby, which would be sensational says Hansen. Even though child mortality was high at that time, child mummies are less common and mummies of new-born babies are very rare in collections.

So when the mummy went through the scanner, Hansen was not overly surprised to see that it was in fact empty. But it can still be of interest for scientists, she says.

“The Vatican are currently running a project, studying empty mummies to find out what they’re really all about. Are they all “modern” souvenirs, or are some actually from ancient times? Were they constructed in a systematic way? If they’re not old, which I don’t think this one is, it’s still very interesting in relation to the tourist market at the time,” she says, adding that this particular “mummy” may have arrived in Denmark in the 18th century.

Giving old mummies new life

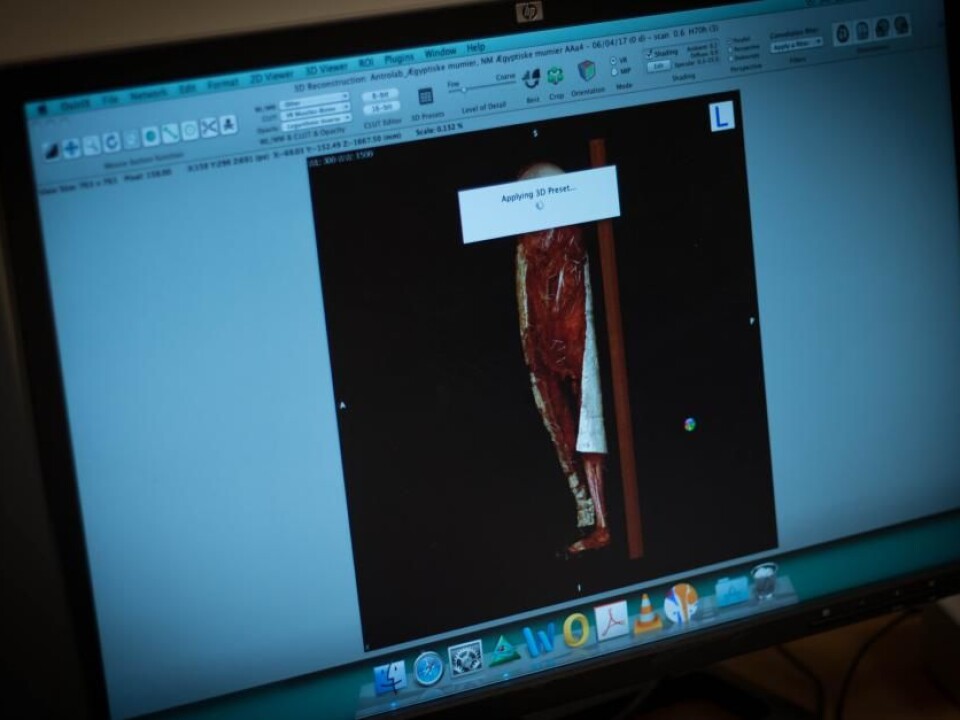

While the scientists scan the three mummies, the first 3D images begin to emerge on the computer screen next to us. Later, they will be converted into 3D models.

The scientists hope to be granted access to scan more of the museum’s mummy collection.

For Haslund Hansen, the day was a big success.

“It’s been a really good day. I can now go home with entirely new knowledge about these artefacts. I’m really pleased that we’ve learnt a lot, especially about the child mummy, because that has been a curiosity for so many people for so many years,” says Hansen.

The child mummy has been on display for many years--it was exhibited in the so-called Royal Kunstkammer in Copenhagen in the 17th century--and the new information gained through the CT-scan can breathe new life into this old museum exhibit, says Hansen.

“We might now be able to make the case that it shouldn’t be seen as it was in the past—a curiosity, something mysterious and strange. Hopefully, we can now give this child a biography, which is somewhat closer to the life that it lived in Ancient Egypt, so it’s not just a “mysterious mummy.” I think that’s really great: to give it new life.”

---------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex