Denmark’s first Viking king printed in 3D

Full reconstruction of Gorm the Old reveals a strange growth on his neck.

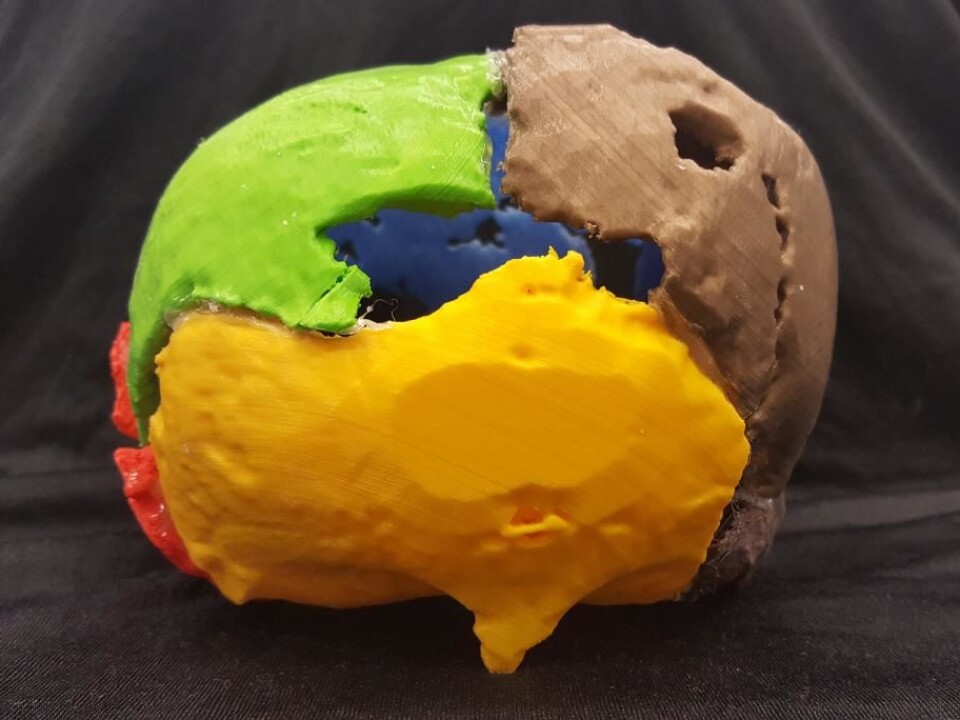

For the first time ever, bones from the famous Danish Viking king, Gorm the Old, have been reconstructed and printed in 3D.

Gorm the Old was the first to call himself king of Denmark. He was also the first to use the name ‘Denmark’ for the country he reigned over for decades until his death in 958 CE.

Even though the bones are damaged and parts of the skeleton are missing, being able to hold pieces of one of Denmark’s greatest kings is a unique experience, says archaeologist Adam Bak, curator at Kongernes Jelling, National Museum of Denmark, who facilitated the reconstruction.

“It’s a great feeling to stand with them in your hand, turning them over, and looking at them. From a pure science communication perspective, it’s so much better to have a ‘real’ bone in your hand than to read a dry text about a, historical person. I can’t deny that I’ve also played Hamlet with his skull,” says Bak.

Read More: Archaeologists finally know how old Denmark’s fifth Viking fortress is

Gorm had a ‘bird’s beak’ on his neck

Scientists used a CT-scan of the bones, which have since been reburied under the church in Jelling, to reconstruct them with a 3D printer.

3D scans allowed them to adjust for the pressure damage that occurred after burial, says Marie Louise Jørkov, a postdoc in the Section of Forensic Pathology at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. For example, the skull had been flattened after being buried for so many years.

“Then you can print the bones one to one in 3D, which makes it possible to display the bones. We can then re-analyse the skeleton and study the bones to look for any signs of disease, which can’t be seen at the surface,” says Jørkov.

The reconstructed bones revealed a rather odd lump on the back of Gorm’s head.

“He had a very pronounced growth on his neck just where it meets the back of the head. It looks like a bird’s beak and it’s really pronounced. It’s not totally unheard of, but we don’t see it very often,” says Jørkov.

Read More: This tiny ornament may have belonged to Harold Bluetooth’s shaman

Bones react to pressure

In medical terms it is known as an external occipital protuberance. It occurs when the bone that the neck muscles attach to grows too much.

The bird’s beak would only have been visible if Gorm had short hair or bare scalp, says Jørkov.

According to Carsten Reidies Bjarkam from the Department of Biomedicine at Aarhus University, Denmark, such a growth could be the result of a load on the muscles and ligaments that connect to the protrusion.

“It can be best compared to a bunion, which is also a response to a sustained load. The bone simply grows more at that spot than is normal. It’s a normal reaction, which has gone overboard in his case,” he says.

According to Bjarkam, Gorm most likely suffered no serious symptoms from the growth and neither would it have had any effect on his brain function or movement.

But it was probably painful to sleep on and he most likely slept on his side. “It wouldn’t have been nice,” says Bjarkam.

Read More: Why Danish Vikings moved to England

Limitations with earlier scans

Gorn the Old’s bones were first discovered under the floor of Jelling Church in 1978, though written sources record that he was originally buried in the North Mound in Jelling.

After their initial discovery, archaeologists from the National Museum of Denmark studied them and made a CT-scan before the bones were reburied in 2000. But the resolution of these early scans was not good enough to draw specific conclusions on many aspects of the man himself.

For example, his age could not be narrowed down to anything better that between 35 to 50—a relatively large spread since 50 was a ripe old age for a Viking, while 35 was still a relatively young age to die.

Read More: See where the Vikings travelled

Time for Gorm to rest in peace?

In the original studies it was not possible to extract DNA from the bones. Theoretically, they could not be absolutely certain that it was actually Gorm the Old who had been buried in Jelling Church.

The museum is often asked why they do not just exhume the bones again to study them using all the newly available techniques. The answer is that this is an issue for the church and the royal family.

Partly it is a consideration of what you hope to get out of it, says Bak.

“He’s been in the grave for 800 years, which for much of that time was under water, and his bones are very damaged. I doubt that it’s possible to extract DNA or strontium [a trace element that can say something about where a person was born and lived]. Moreover, he’s been disinterred three times now, so it’s also a question of allowing him to rest in peace,” he says.

----------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex