Why Danish Vikings moved to England

As many as 35,000 Vikings migrated from Denmark to England, reveals a new study. But what made them embark on such a drastic step to move west to a new land?

Despite the dangers, between 20,000 and 35,000 Danish Vikings chose to uproot and migrate to England between the 9th and 10th century. So says a new study published in the archaeological journal Antiquity.

Initially the trips were raiding expeditions, but later on, more and more Vikings decided to stay in the new land to the west, cultivate land, and “proceeded to plough and to support themselves,” according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 876.

But why did so many Vikings say farewell to the security of their homeland, friends, and relatives to move to a new country?

If you ask Viking researcher Søren Sindbæk, a professor with special responsibilities in the School of Culture and Society from Aarhus University, Denmark, the reasons behind the wave of migration in the 9th and 10th centuries were driven by the same factors that drive migration to Europe today: the chance of a better life.

“It’s the same thing that made people travel to America or Australia a couple of hundred years ago. New transport options developed in the 9th century, and people began to use sailing ships on a large scale. At the same time, the Vikings who went to England to plunder, realised that they could also use their military power to acquire land,” says Sindbæk.

Read More: New study reignites debate over Viking settlements in England

Vikings first hunted after portable treasures

The Viking’s initial trips to England were more or less unsystematic raids. But by the latter half of the 9th century, the Scandinavian Vikings had organised themselves into a large army, often referred to as the Great Heathen Army or micel here in Old English.

“The initial raids were about the need for portable wealth (‘treasure’) that could be taken back to Scandinavia (mainly Norway) to help in building allegiances between lords, their followers, and other families and communities, and perhaps also in marriage relations,” writes Viking scientist and archaeologist Steven Ashby from the University of York in an email to ScienceNordic.

“These raids were then followed by more concerted attacks by the Great Army, who soon come to appreciate the value of land. Many settled down as rural landowners, and became part of a new ‘English’ elite,” writes Ashby.

Read More: Old DNA reveals Viking impacts on flora and fauna

New farming opportunities in England

These initial raids revealed that The British Isles had more to offer than mere treasure to be stolen. They also offered lands that could be cultivated.

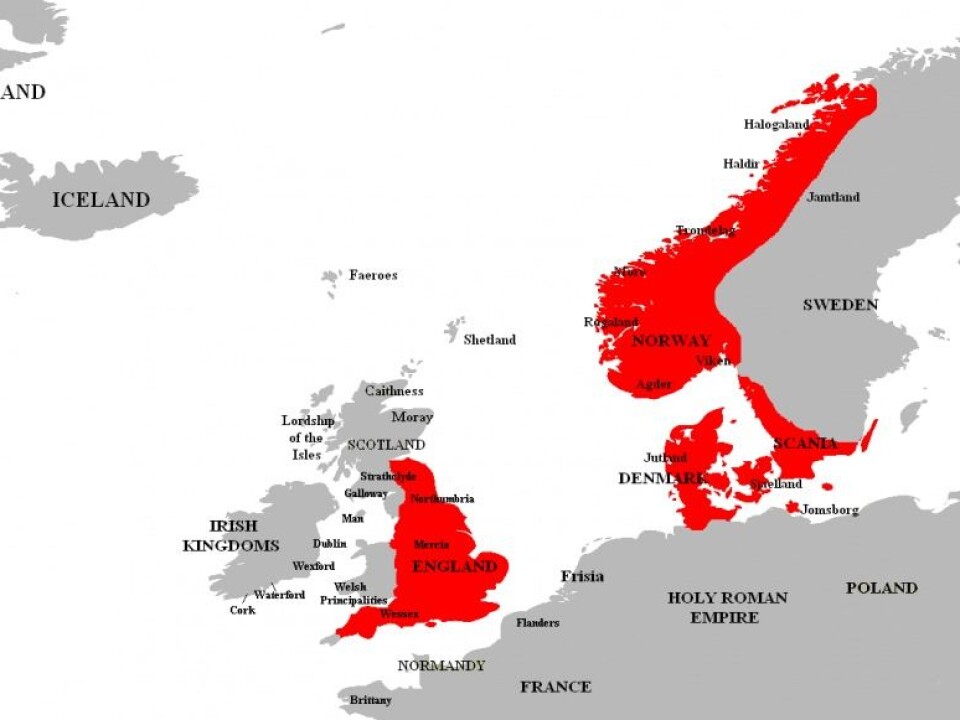

Explore the time-line above to follow the Danish Viking travels to England (Graphic: Mette Friis-Mikkelsen / ScienceNordic)

“The warriors of the Great Heathen Army managed to achieve a position of power, so they could expropriate large tracts of land and say, “Now we should own land here.” The English countryside was far from fully cultivated at this time, which probably played a role. So peasants from Jutland (Denmark) or Norway could thus find a relatively fertile land, where you could easily achieve a lucrative life,” says Sindbæk.

Archaeologist and Viking researcher Jane Kershaw, a postdoc at University College London agrees.

“In eastern England the Vikings discovered a milder climate and a rich agricultural landscape, similar to the one they knew back home. Faced with a lack of good farming land in Denmark, many families decided to try their luck on the other side of the North Sea,” says Kershaw.

Read More: DNA study: Vikings were plagued by intestinal parasites

Vikings settled England as they did Iceland

The same pattern of exploration and then, later, settling down to farm, also occurred in Iceland, says Sindbæk.

“It fits well with the story in England: there was a first phase where warriors plunder and come home with the spoils. The warriors also discover the opportunities of England and some Vikings travel back to settle down and cultivate the earth,” he says.

“Back then, if you were a young warrior that wasn’t set to inherit the family farm back home, you suddenly had the chance to be your own man by heading to England and becoming a farmer. Later, you could send a message home to say that you’d won wealth and honour and ask relatives to send suitable women to England to marry,” says Sindbæk.

Read More: Viking invaders struck deep into the west of England and may have stuck around

Did Vikings take their wives with them?

Kershaw has long argued that it was not only men that travelled from Scandinavia to England. She thinks that high numbers of Scandinavian women travelled to England too.

“If you took family and friends to England, you had a network in the new land. In that way, Vikings could continue to speak their own language, dress in their own style of clothes, use their own currency system and even retain aspects of their legal system. Migrating as part of an extended network likely made the prospect of moving to England less daunting”, says Kershaw.

Kershaw thinks that many women travelled to England due to a series of new discoveries of metal jewellery from Viking Age England.

Increased use of metal detectors has led to the discovery of more and more female jewellery and costume items. Kershaw believes that the jewellery has a Scandinavian origin and was brought to England by Viking women.

“Scandinavian women typically used brooches to fasten and adorn their clothing. In recent years, these finds have started to emerge from the ground in England in large numbers. The jewellery is clearly Scandinavian in style and doesn’t resemble the jewellery traditionally used in England at this time. Also, the distribution of the jewellery is rural and dispersed: this doesn’t fit with a scenario in which it arrived via trade, but does make sense if women are wearing, and losing, these dress items on their farms. I’ve long argued that this indicates that there were a lot of Viking women in England,” says Kershaw.

The fact that the Scandinavian language survived in England for several generations also suggests that Scandinavian-speaking women passed on their language to their children, she says.

Read More: Genetics confirm: Migrants brought farming to the Mediterranean

Big debate on the number of Vikings in England

Ashby points out that while this may be true, there are many other finds that point in the other direction.

“This argued against earlier work, which showed that cloth made in England was still made in a very 'Anglo-Saxon' way, rather than a Scandinavian way. As weaving was a woman's job in the Viking Age, this might suggest that there weren't very many Scandinavian women in England at the time,” he says.

“The key problem is that different forms of evidence will often give different answers, as they are telling us different things,” says Ashby.

Historians and archaeologists are locked in a fierce debate over how many Vikings actually travelled to England. Some put the figure at a few hundred, while others think tens of thousands settled.

Read More: Viking sailors took their cats with them

Sweyn Forkbeard conquered England

Regardless of how many it was, the Vikings certainly had an effect on the British Isles.

Danish laws formed the basis of the Dane Law, and gave the name “The Danelaw” to an area in north and east England that came under Danish control in the latter half of the 9th century.

The Viking raids culminated in 1013 CE when the Viking King Sweyn Forkbeard conquered the whole of England. And if you believe the results of the new study, tens of thousands of Danish Vikings also moved to England at this time.

“If it’s correct, then the study shows that there was quite a large and well established Danish population in England during Sweyn Forkbeard’s time. It also makes it easier to understand why the Danish King was accepted. There was a large group of Scandinavians in England who had already integrated into the population for 100 years,” says Sindbæk.

Read More: Scientists embark on the world’s largest genome project

Massacre of Danes in England

According to the new study, the main wave of Viking migration took place between 800 and 900 CE. The Danish King seized power over the British Isles in the 11th century, which is also when the wave of Viking migration ended—perhaps because the new Scandinavian arrivals were not overly popular in their new home.

“They were definitely tired of immigrants in England around the 11th century. There was an episode in 1002 CE, where the English King commanded that all the Danes in England should be killed. We don’t know how many were actually killed, but there’s no doubt that a mass murder took place,” Sindbæk.

This mass murder became known as the St. Brice’s Day massacre.

“This episode underlines that the Vikings were such a large population group that the Danes were seen as a political force—and in some contexts, a problem,” he says.

Even though it is more than 1,000 years ago, the Viking travels to England continue to be an event worth studying because we can learn about our past, says Kershaw.

“Today, we live in a time with large scale migration. We see many migrants and refugees coming to Britain, just like the rest of Europe. Migration is a part of our culture. We should open our eyes to the fact that the same happened 1,000 years ago, instead of thinking about our ancestors as people who were settled and never left their farm,” says Kershaw.

----------------------

Read the original version of this story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

- "The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population", Nature 2015, doi:10.1038/nature14230

- "The ‘People of the British Isles’ project and Viking settlement in England", Antiquity, 2016, DOI: https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.193