Genetics confirm: Migrants brought farming to the Mediterranean

Scientists have sequenced the genomes of early farmers from Spain, confirming that they descended from the same group of migrants who brought farming to Northern Europe.

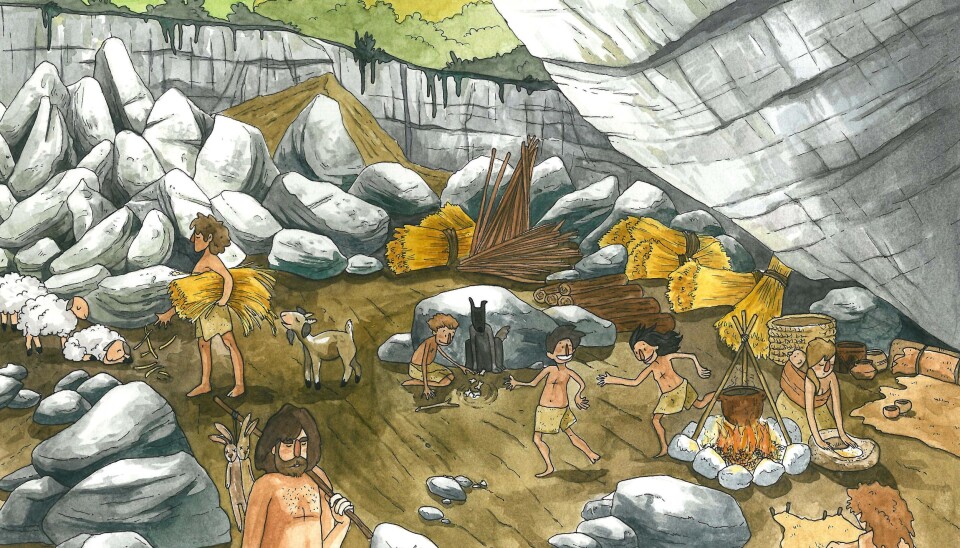

Ten to eight thousand years ago, Europe was facing a cultural revolution.

Migrants from the Near East were moving into Central and Northern Europe, bringing with them knowledge of farming practices and transforming the existing European hunter-gatherer life-style.

Now, scientists have confirmed for the first time, that these newcomers also made it down to Spain.

In two independent studies, scientists present the first complete genome sequences of early farmers from the west Mediterranean.

“We’ve seen in both Scandinavia and throughout central Europe that migration of people from the Fertile Crescent in the Near East brought farming techniques to Europe,” says Mattias Jakobsson, professor of genetics at Uppsala University, Sweden, and co-author of one of the new studies.

“Now we can finally say the same for Iberia,” he says, talking about the new research, which has just been published today in the scientific journal PNAS.

Europe’s earliest farmers came from the east

In the second study, published in the scientific journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, a separate team of scientists have come to the same conclusion: Europe entered a new agricultural age thanks to migrants.

“The main finding from both our study and Jakobsson’s study, is that early European farmers have a common origin,” says co-author Hannes Schroeder, assistant professor at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

Specifically, these migrants came into Europe through the Balkans from an area of the Near East, which today includes East Turkey and parts of Syria.

Peter Ralph, is an Assistant Professor in evolutionary biology and population genetics at the University of Southern California, USA, and has read both of the new studies. He was not involved in the research, but thinks that together the two studies add to the emerging picture of human history as told through our genetics.

“Of particular interest is that these two studies help to confirm the emerging story as to how farming came to Europe, and how people intermixed over time with the existing populations,” says Ralph.

According to him, a coherent picture of the history of human migration and settlement is emerging, and whilst we only have DNA from a handful of individuals so far, these two studies together add another piece to the jigsaw.

DNA tells a 4,000-year story of human migration

Collectively, these two studies shed light on human genetic history in Iberia from roughly 7,400 to 3,500 years ago.

Both studies sequenced the DNA from ancient humans from Spain, and compared this with the DNA sequences of other ancient Europeans.

Jakobsson and his team studied the fragments of human teeth and bone from the Sierra de Atapuerca, in northeast Spain, around 5,500 to 3,500 years ago.

Meanwhile, Schroeder and his team analysed 7,400 year-old human remains from Barcelona, Spain, and the west coast of Portugal.

“Our study is looking at an earlier group of people, which probably represents some of the first farmers to arrive in Spain. So, whilst the two studies are mostly in agreement, there are also some differences, which can probably be explained by the fact there are about two or three thousand years between the samples,” says Schroeder.

“Specifically, in our study we see, that whilst these new comers had not yet mixed with the local hunter-gatherers in Spain, they had been mixing with hunter-gatherer groups they met along the way from the east,” he says.

Jakobsson’s team pick up the story 2000 years later. By this time, the ancient humans that they studied were no longer new comers to the area, and their DNA results showed that they had been mixing with the local hunter-gatherers in Spain.

The Basques: just how unique are they in Europe?

A big topic of discussion in this part of Spain, is just how unique is the Basque culture?

By comparing the ancient DNA to that of modern Europeans, the two studies give us some answers, at least in terms of biology.

The two studies show that the DNA of the newly arrived migrants, 7,400 years ago, is actually more closely related to other modern day Europeans, like the Sardinians. However, by 5,500 years ago, things had changed, and the settlers DNA had become much more similar to that of the modern day Basques.

So what does this mean for Basque history?

“It’s interesting that 10 to 15 years ago, people claimed the Basque can trace their roots back to local stone age hunter gathers, who pre-dated European agriculture, making them rather unique in Europe. We now see that this isn’t true, but the modern day Basque people can still claim to be unique to a certain degree,” says Jakobsson.

“Even though they clearly share common ancestry with early European farmers, we can see now that they have been rather isolated, genetically speaking, for at least the last 5,000 years,” says Jakobsson.

Jakobsson and Schroeder agree that the Basques are still unique compared to all other modern day Iberian groups.

“Over the past few thousand years this region has a history of invasion and migration from North Africa, and yet in terms of the genetics, the Basque population have remained rather isolated,” says Schroeder.

Professor Morten Erik Allentoft from the University of Copenhagen also studies ancient genetics. He was not involved in either of the studies but says they shed new light on Basque history.

“I think the really novel aspect here is the link to the Basques that is recognised by both teams, despite using samples from different periods and sites,” says Allentoft.

“The genetic origin of the Basques has long been a mystery and with these new data we are getting closer to understanding the population history of these people,” he says.

Genetics can also tell us about linguistics

Schroeder suggests that this isolation is also reflected in the linguistic history of the region.

“The Basque isolation is also reflected in their language, which doesn’t share a common root with other Indo-European languages,” he says.

According to him, given what they now know about the common genetic ancestry of the ancient humans in both studies, it is likely that none of them spoke an Indo-European language.

This probably came later, with the large human migrations during the Bronze Age, around 3,000 years ago, and had little influence on the Basque people who retained their local language from these early European farmers, says Schroeder.

Scientific links

- PNAS study: “Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques.” DOI 10.1073/pnas.1509851112

- MBE study: “A common genetic origin for early farmers from Mediterranean Cardial and Central European LBK cultures.” Doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv181