Archaeologists are hunting for Greece’s underwater past

There is so much to uncover that we most likely won’t be done during my lifetime, says the archaeologist leading the excavation.

“Not everyone can go to Corinth.” So says a Greek proverb from antiquity, hinting at the fact that you would have needed a heavy wallet to visit the prosperous city-state.

The city-state was positioned on the small strait linking the Greek mainland and the Peloponnese peninsula. It controlled all shipping between the eastern and western Mediterranean.

Ships could moor at Corinth and be dragged safely across to the other side, thus avoiding the perilous trip around the treacherous waters of the Greek peninsula.

“But when you sail around Cape Malea, forget your home,” wrote the Greek geographer Strabo about the peninsula in the first century BCE—meaning that you were unlikely to make it home.

Corinthians were well paid for their troubles, and the port of Lechaion thrived. Today, archaeologist Bjørn Lovén from the University of Copenhagen is once again benefiting from the Corinthian trade, as he leads an excavation of the ancient port.

Read More: A 2,500-year-old city found in Greece

A throng of life

“It was once a throng of life bustling with sailors, wares, and cattle being dragged to and from the ships. Lechaion was a vast enterprise and one of the world’s most important trading places of ancient times,” says Lovén.

After three years of excavating, Lovén and his team have now reached the inner harbour. So far, their meticulous excavations have uncovered channels, piers, and wharfs.

But their dream would be to discover a trireme—a type of ancient Greek ship that according to ancient sources was invented in Corinth.

“It’s not very realistic. But then again, people told Edison that his filament would never light up. The trireme is my holy grail. We only know the rough dimensions, not how it was built, or what type of tree it was built with. They’re probably out there. And Lechaion is a good place to search,” says Lovén.

The sea around Lechaion is a mixture of fresh and salty water, which means that woodworm do not survive there. So archaeologists have discovered numerous examples of well-preserved ancient wood in the harbour.

Read More: Archaeologists discover Athens’ oldest navy base

Lifetime of discoveries yet to make

The 46 year-old archaeologist has plenty of time to make his dream discovery.

“The area is enormous and complex and still holds many secrets. It’s possible to excavate in Lechaion for the rest of my life. And that’s my plan,” says Lovén.

“The most beautiful thing about Lechaion is that there is so much to excavate that it will be up to the next generation or the generation after to finish the work.”

Read More: Bull fat, bats blood, and lizard poop were the drugs of choice in ancient Egypt

Dreams come true

Just being allowed to excavate at Lechaion is a dream come true for the Danish archaeologist.

“When I stand of the beach at Lechaion, I think about how the seeds of Europe were laid here, when colonists went west and founded Corcyra on Corfu and Syracuse on Siciliy, which also became powerful city-states. I see traders and warships passing by and I can’t stop thinking about what else lies at the bottom of that sea,” says Lovén.

“I feel very privileged at being able to excavate one of antiquity’s most important trade ports. It’s not just about Greek history or European history. It’s the whole world’s history,” he says.

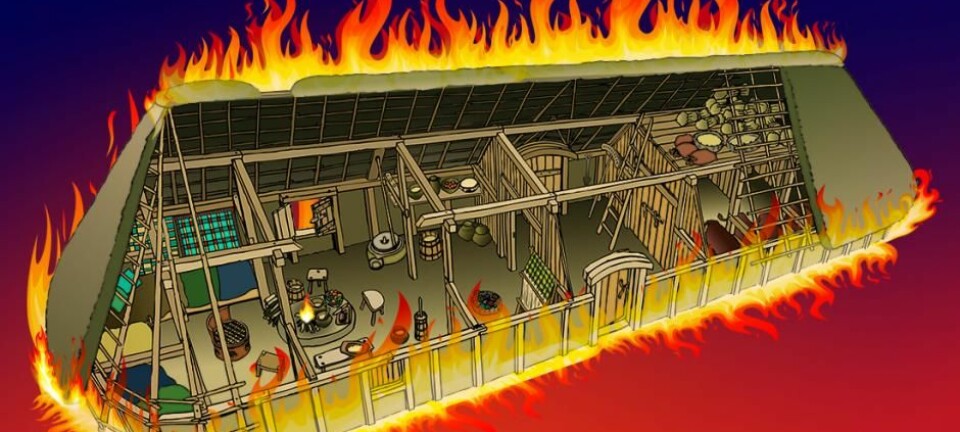

See how Lechaion may once have looked, according to archaeologists’ impressions, at the top of this article.

---------------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex