Cave paintings and bones reveal origins of European bison

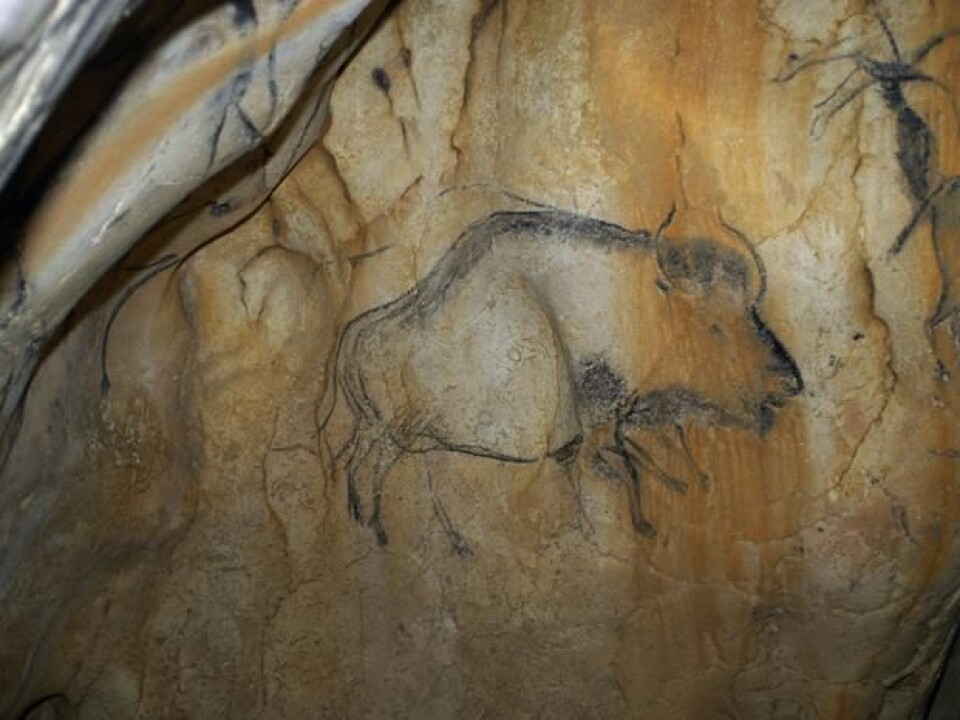

Fossil DNA from bison bones reveals that the European bison was a cross between aurochs and bison. Cave painters depicted the species in detail, 15,000 years ago.

A unique combination of fossil DNA and ancient cave paintings has solved the mystery of the origins of European bison.

A team of scientists from the Australia, Russia, UK, and Denmark have discovered that the European bison originated as a cross between aurochs and steppe bison, 120,000 years ago.

“It’s truly surprising that cross breeding between two mammals has lead to the formation of a new species. ve been able to cross bred. It shouldn’t be possible. It was there the whole time, we joust couldn’t see it,” says co-author Alan Cooper, from the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at the University of Adelaide.

“It’s a fascinating article and it helps explain why it’s so difficult to distinguish between aurochs and bison bones,” says postdoc Jennifer Crees, who studies ice age animal remains at the Zoological Society of London, UK.

The study is published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

Mysterious DNA among thousands of bison bones

Bison were once widespread around the world and The Natural History Museum houses many thousands of bison bones that cover a wide range of dates and habitats.

Their ancestors, steppe bison, roamed throughout America and Europe during the ice age.

But a study of these bones contained some surprising traces of DNA in their bones.

Read More: Scientists: Rewilding is a Pandora’s box

The mysterious bison is a “Higgs Bison”

The strange DNA is similar to that of the present-day European bison in Poland, although there are a few differences.

“We began to call the mysterious species “bison-x” and the “Higgs-bison,” because we couldn’t find out if it was real or not,” says Cooper.

Cooper and colleagues believed that they had stumbled upon an ancestor to today’s European bison, which appears in the fossil record shortly after European steppe bison went extinct.

One hypothesis was that Bison-X was a hybrid between aurochs and steppe bison.

Cooper and colleagues have until now produced species maps based on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)--a part of the DNA that is handed down from mother to daughter. While it draws connections between generations, it does not give the complete picture.

To check whether Bison-X was indeed a hybrid, they studied the rest of the nuclear DNA.

“We discovered that the nuclear DNA is bison, and the mitochondrial DNA is auroch. So it's a hybrid,” says Cooper.

Read More: Fossil DNA reveals new theory on colonisation of America

Rescued from the brink of extinction

The fossilised mtDNA closely resembles that of contemporary bison, but with some differences.

The last European bison died out during the First World War, and the species was only brought back from the brink of extinction by conservation in zoos.

“All living bison are descended from 12 individuals. This greatly changes the genetic profile,” says Cooper.

Today there are approximately 4,000 bison, but they represent only a small sample of the original genetic variation of the species. So it is likely that Bison-X represents an ancestor of these modern day bison.

The next step was to compare the fossils of Bison-X with modern day animals.

The appearance of European bison is quite distinctive from steppe bison. The latter have long horns and a large frontal structure like the American bison. European bison have a smaller hump and short double-curved horns.

Unfortunately, they only had bones from the femur and ribs to analyse, which do not reveal the animal’s distinctive body shape.

But cave art in France and Spain, could.

Read More: Mysterious bear figurines baffle archaeologists

Cave paintings show bison’s origins

It turned out that French experts had long pondered over two distinctive types of bison depicted in the cave paintings by Stone Age artists.

Cave painting depictions of bison suddenly changed during the transition to Magdalenian culture. Until 25,000 years ago, cave art depicted long-horned bison. But this changed around 18,000 to 20,000 years ago, when they started to draw short horns.

Together, evidence from DNA and the cave art had confirmed the origins of a new species of bison.

Read More: Earth set for large-scale wildlife reshuffle

Hybridisation is an important mechanism

The fossil DNA suggests that the bison hybrid first appeared at least 120,000 years ago from an aurochs mother and steppe bison father.

The nuclear DNA is stabilised at a ratio of 90 per cent steppe bison and just 10 per cent aurochs, indicating that the hybrid went on to breed with a herd of steppe bison.

Eventually the hybrid became a new species in its own right.

“What we found was quite bizarre, and doesn’t usually happen in mammals. But it shows that hybridisation is an important adaptation and speciation mechanism,” says Cooper.

He says the hybrid population must have developed in isolation from both parent populations, and within a new environment--possibly due to sudden changes in climate.

Read More: Grizzly-polar bear hybrids spotted in Canadian Arctic

We have so much yet to learn

“In light of this research, it’s crucial to examine the fossils from the ice age and see if we can reconcile them with these genetic discoveries of a form of hybrid,” says Crees.

Cooper is certain that the museum’s vast collection of bones will contain a sample of Bison-X skull, and he hopes that the museum will now look for it.

“I’m certain that there’s been far more diversity and much more dynamic changes in response to climate change,” says Cooper.

“We know that the most common fossils are from this species, and at the same time we have cave paintings that have helpfully captured these animals. And yet we still can’t figure out exactly what happened,” he says. “So you have to ask, how much are we really missing?”

-------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex