Earth set for large-scale wildlife reshuffle

Totally new climate regimes have already emerged this century and further changes are likely to cause new species assemblages to appear throughout the world, shows new study.

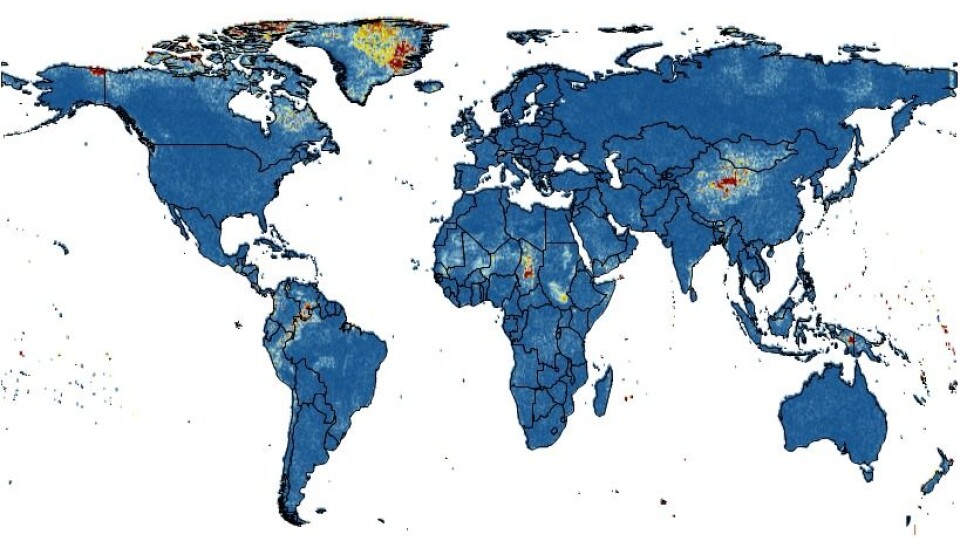

Totally new climate regimes--new combinations of average rainfall and temperature--have emerged in 3.4 per cent of the Earth’s land surface during the past 100 years, shows a new study published in Nature Climate Change.

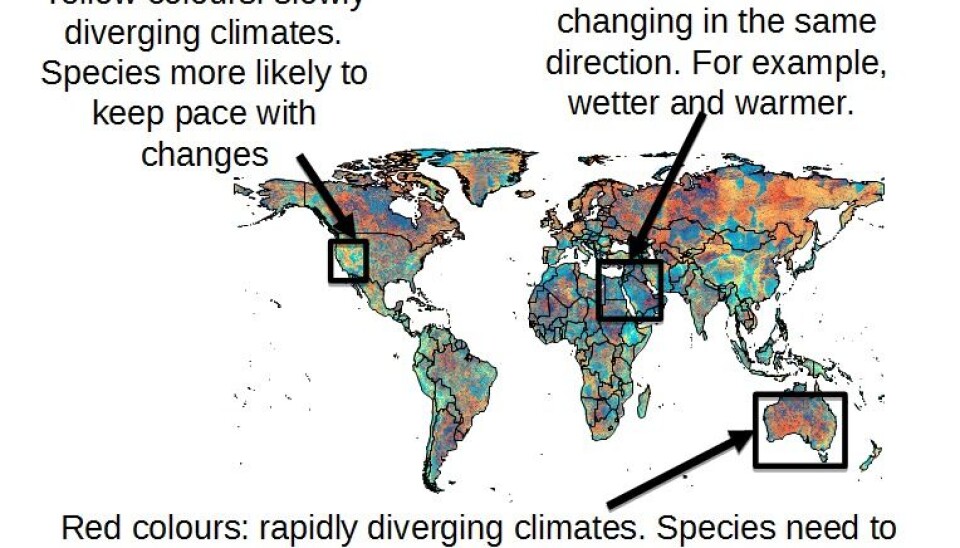

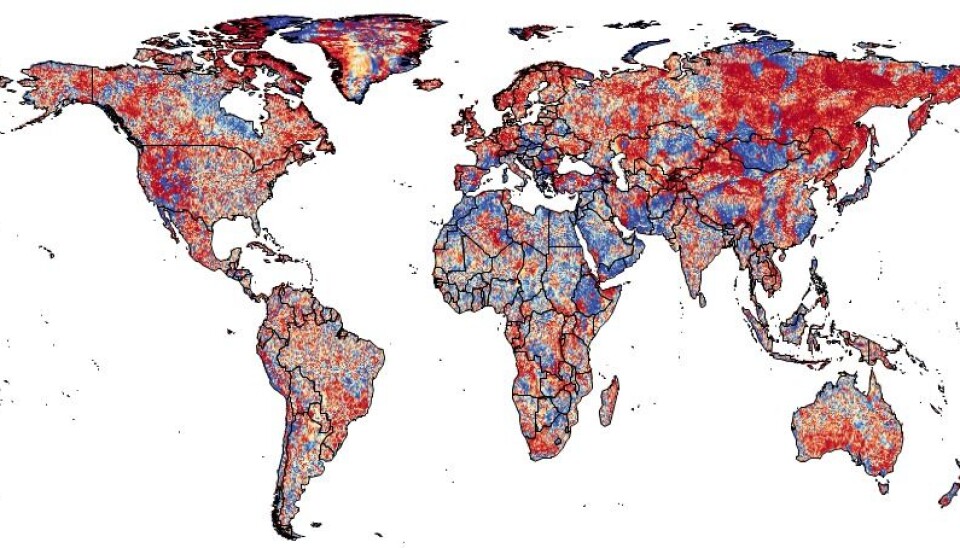

Meanwhile, 67 per cent of land on Earth is experiencing rapid and divergent changes. For example where temperatures are increasing, but rainfall is decreasing. This puts wildlife under increasing pressure to either adapt to these divergent conditions or move to somewhere more suitable.

“We see in parts of California, northern Europe, and southern Australia, temperature and precipitation regimes are moving very fast and in some cases, in completely different directions,” says lead-author Alejandro Ordonez from the Department of Bioscience at Aarhus University, Denmark.

“Species are having to make a decision as to what is more important to them. They either track temperature or precipitation,” says Ordonez.

Climate change is just getting going, and yet the impacts are already piling up.

The study concludes that new species assemblages could already be emerging across the Great Plains and temperate forests of North America, the Amazon, South American grasslands, Australia, Asia and tropical Africa as a result.

Set for wide-spread environmental reshuffle

These new results confirm that we have now started down a path towards wide-spread reshuffling of climate conditions and ecosystems that was predicted in a study published in 2007.

This previous study predicted that up to 39 per cent of the Earth’s surface could experience novel climates by the year 2100, based on projected future scenarios of climate from the fourth IPCC report. The new study now provides evidence that this process is already under way.

“If this continues, and is coupled with the high local displacement and divergence of climate regimes shown in our paper, then it could lead to the emergence of novel species assemblages around the world and other unexpected ecological responses,” says Ordonez.

Professor Jonathan Overpeck is a climate modeller and the co-director of the Institute of the Environment. University of Arizona, USA. He was not involved in the new research but is impressed with their approach and findings.

“It's very cool how the authors reduced climate change down to such innovative metrics of change that can drive the emergence of species assemblages unlike anything now in existence. We’ve known this can happen, and indeed has happened in Earth history, but now we have new ways to anticipate where, when and what kind of novel climate drivers are taking place,” writes Overpeck in an email to ScienceNordic.

Read More: Ecosystems driven out of sync by climate change

Climate combinations never seen before

To reach their conclusions, Ordonez and his colleagues compared maps of average annual temperature and total rainfall from around the world to see where new combinations of temperature and rainfall have emerged since the early 20th century.

“There are two bullseye locations, one in the tropics and one over Greenland,” says Ordonez. But he does not place much emphasis on changes highlighted in Greenland. Here the emergence of new climate regimes is difficult to relate to species, as these changes occur over the largely uninhabited Greenland ice sheet.

“But when we look at areas like the border between Columbia, Brazil and Venezuela, central Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and parts of the Himalayas, this is where based on our assessment, we’re already seeing novel climates emerging,” says Ordonez.

Read More: Grizzly-polar bear hybrids spotted in Canadian Arctic

Future hotspots of change across northern Europe, Russia, and the US

The scientists then mapped the speed at which rainfall and temperature regimes were changing from one location to another and in what direction, so-called divergence, to see how and where wildlife may become unceasingly hard-pressed.

For example, temperature and rainfall can diverge in mountainous regions where climate change allows warmer temperatures to spread up-slope towards the summit while rainfall regimes move down-slope in the opposite direction. Or as temperature regimes shift towards the poles, rainfall patterns could shift towards the equator. These diverging conditions place species under increasingly difficult and unpredictable conditions.

“This would be where ecosystems and the species in them are under the most pressure to respond. And if on top of that you have very high rates of change, then this is a recipe for the emergence of novel species assemblages,” says Ordonez.

Such hotspots are likely to appear across Australia, northern Europe, north America and vast tracks of Russia and East Asia, he says, and conservation managers in these regions should plan for rapid and divergent climate change.

Read More: Take a tour of an Arctic monitoring site

Difficult choices ahead for wildlife: water vs. temperature

At some point in these hotspots, species will have to choose how to respond to new, diverging environmental conditions, says Ordonez.

Birds living on a mountain slope may have to choose to move up-slope following warmer temperatures even though there is less water available. Or they could move down slope to follow local rainfall, even though it is becoming too warm for them.

“There are a couple of studies that have already shown this,” says Ordonez.

A study of more than 400 different bird species in Australia discovered that they are relocating in many different directions, while the tree-line (the altitude limit of where trees can grow) in the Californian Sierra is shifting in all sorts of directions in response to recent climate change, he says.

Read More: Extreme weather in the Arctic causes problems for people and wildlife

Colleague: important assessment of 20th century climate

Assistant Professor Gregoire Mariethoz from the Faculty of Geosciences and the Environment at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, was not involved in the new research but has read the paper.

Mariethoz is the head of a research group studying geostatistics and hydrology and is familiar with some of the methods used in the study. He speaks positively of the results.

“The conclusions are clear and supported, and this paper brings an important quantitative assessment of the climate evolution during the instrumental period,” says Mariethoz.

“One very interesting aspect is that this research is purely data-driven: the findings are based on observational evidence, which is generally more solid than studies only based on [climate] models,” he adds.

Overpeck believes that the results may give a sense of what is to come and provide hypotheses for other scientists to test.

“It's excellent work. Climate change is just getting going, and yet the impacts are already piling up. The recent changes captured by this team provide a sense of where the climate is going, with bigger changes ahead,” says Overpeck.