Can the BCG vaccine protect against Alzheimer's disease?

It looks promising, says a Norwegian researcher. Influencing the immune system may be able to prevent Alzheimer's disease.

The BCG vaccine prevents tuberculosis and consists of live, attenuated bacteria.

Attenuated bacteria are weakened bacteria used in vaccines to safely stimulate the immune system without causing the actual disease.

The vaccine is no longer offered to all children in Norway, but only to children with parents from countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis.

BCG stands for Bacillus Calmette–Guérin, named after the French researchers who developed the bacterial strain used in the vaccine in 1910.

BCG is also used to treat bladder cancer. The weakened bacteria are delivered to the bladder, where they stimulate the immune system to attack the cancer cells.

In recent years, researchers have seen signs that BCG may also prevent Alzheimer's disease, according to The Guardian.

Developed Alzheimer's disease less frequently

The newspaper highlights an Israeli study from 2019. The researchers looked at data from around 1,300 patients, some of whom had received BCG as treatment for bladder cancer, while others had not.

2.4 per cent of the patients who received BCG later developed Alzheimer's disease, compared to 8.9 per cent in the other group.

In an American study with around 6,500 patients with bladder cancer, the researchers observed the same trend. Patients who had received BCG treatment had a lower risk of developing dementia afterwards.

A meta-analysis from last year, which reviewed several studies, found that the reduction in risk appears to be 45 per cent.

But it is too early to determine whether the vaccine really makes a difference – or if something else is at play.

Needs to be confirmed by other types of studies

“This is promising, but this is data based on associations,” says Tormod Fladby.

He leads the Clinical Neuroscience Group at Akershus University Hospital and researches Alzheimer's disease.

The fact that the data is based on associations means that researchers see that those who received BCG had a lower risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. But it is uncertain if BCG is the cause.

It could be something else the group had in common.

To find out if there is indeed a causal relationship, researchers need to do randomised controlled trials where one group receives BCG and the other does not. The groups must be as similar as possible from the start and followed up over several years.

“That’s the somewhat arduous path you have to take. The data indicates that this may be useful to do. Then, likely, more experimental studies will also be conducted on animal models and look at mechanisms that might underlie the finding,” says Fladby.

Have seen the same with other vaccines

The BCG vaccine boosts the immune system.

Håvard Kjesbu Skjellegrind says that it is encouraging to see evidence suggesting that targeting the immune system could help in preventing Alzheimer's disease.

“BCG vaccination is an example of how the immune system can be stimulated,” says Skjellegrind.

He is an associate professor at NTNU’s Department of Public Health and Nursing.

Skjellegrind points out research efforts aimed at exploring the link between dementia and the use of various medications.

“Some research indicates that nearly all medications might increase the risk of dementia, except for vaccines. Vaccines, on the whole, appear to be associated with a lower risk of developing dementia,” he says.

Supports the importance of the immune system

The explanation could involve other factors.

Those who use a lot of medication are generally more ill to begin with. This might make them more susceptible to Alzheimer's disease.

Those who get vaccinated might be more conscientious about their health in general, says Skjellegrind.

“This could partly explain the connection between vaccinations and a reduced risk of dementia,” he says.

Alternatively, it could be that vaccines in general strengthen the immune system beyond the protection they offer against specific infections – and that this has a positive effect on the risk of dementia as well.

In the studies of BCG and Alzheimer's disease, BCG was administered as a treatment for bladder cancer. It is difficult to dismiss the findings by suggesting that one group made healthier choices, says Skjellegrind. He finds the discovery intriguing.

“It supports a hypothesis that the immune system plays a significant role in the development of Alzheimer's disease and neurodegenerative disease in general,” he says.

Neurodegenerative diseases are conditions that affect the nervous system and brain, leading to breakdown of nerve tissue.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is another example of such a disease. In 2022, a study strongly suggested that the Epstein-Barr virus is necessary for developing MS.

A blank spot on the map

The disease process leading to Alzheimer's disease occurs over many years before dementia develops. It seems to take several decades, according to Skjellegrind.

“What specifically initiates the disease process is still unknown. It’s a blank spot on the map,” he says.

Alzheimer's disease was first described by the German physician Alois Alzheimer in 1907.

He performed an autopsy on his patient Auguste Deter, who died at the age of 55. In the years prior, she had poor memory, language problems, and behaved differently than before.

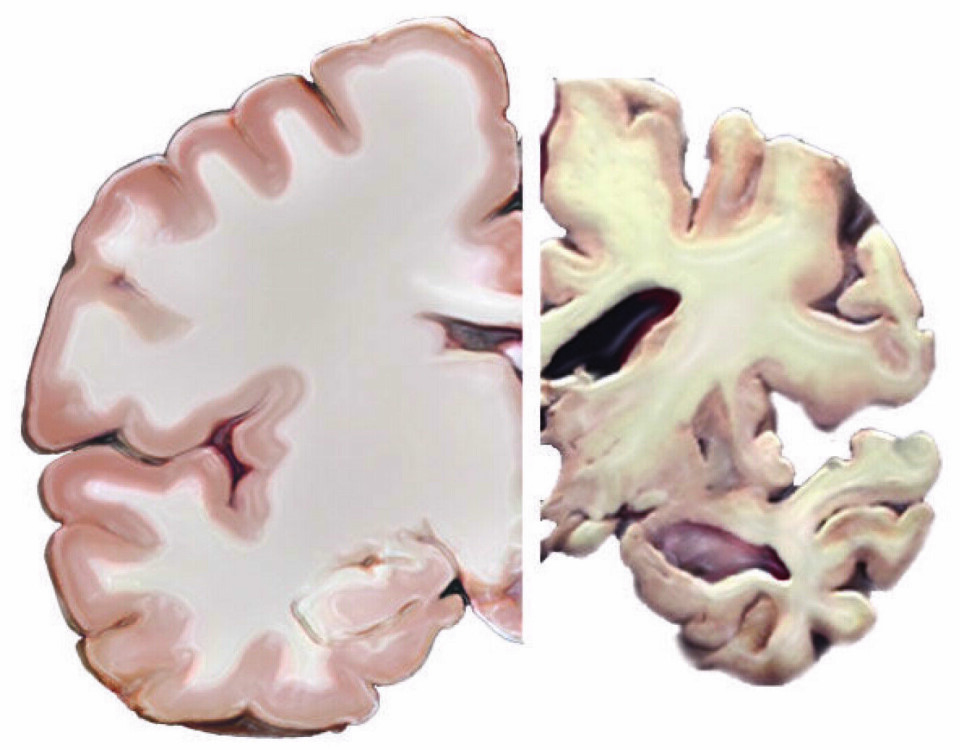

The doctor discovered that her brain had shrivelled and that parts of the brain tissue were gone.

He found deposits of proteins, both inside and between nerve cells.

These proteins are called beta-amyloid and tau. To this day, these remain hallmark characteristics of Alzheimer's disease.

Changes in the brain

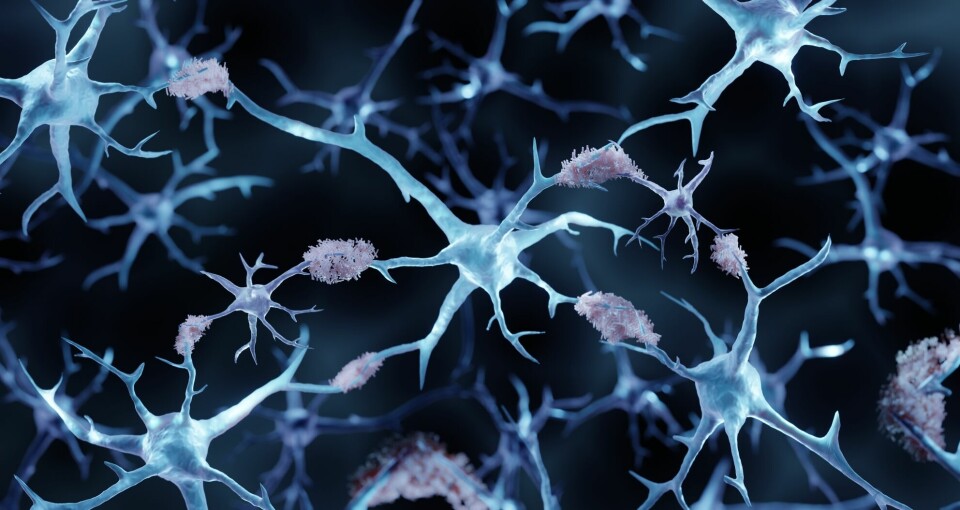

Beta-amyloid accumulates as plaque between nerve cells.

Tau normally helps stabilise the structure inside the cell. In Alzheimer's disease, it starts to detach and tangle.

This seems to lead to nerve cells becoming damaged, ceasing to communicate, and dying.

Researchers have also observed that glial cells, which support nerve cells in the brain, do not function properly in Alzheimer's disease and this can cause inflammation.

There are often also issues with blood supply. This is explained in an article from the National Institute on Aging.

Captures microorganisms?

Why might BCG potentially protect against Alzheimer's disease? A hypothesis is described in The Guardian.

A weakened immune system may allow viruses, bacteria, and fungi to enter the brain.

It is possible that beta-amyloid is produced to eliminate these invading microorganisms.

Supporting this, microbes have been found trapped in beta-amyloid deposits, according to the newspaper.

A 2008 report showed, for example, that the herpes virus, which causes cold sores, was present in 90 per cent of all brain plaque in individuals affected by Alzheimer's.

A type of glial cell, microglia, are the brain's immune cells. They do not function properly in people with Alzheimer's and are unable to clear away the beta-amyloid proteins afterward. This leads to inflammation in the brain.

If this is correct, vaccines or medicines that enhance the body's ability to fight off microorganisms, or that can alter how the immune system works, might help.

A primitive immune system

Tormod Fladby mentions that it is well-known that beta-amyloid has been described as a defence against microorganisms.

“It’s definitely an interesting and relevant connection. There’s a plausible biological mechanism that could be the reason for a potential protective effect of the BCG vaccine,” he says.

Skjellegrind also believes there could be something to this explanation.

“Beta-amyloid has been considered something undesirable that interferes with normal brain activity, a kind of waste that can’t be eliminated. But from an evolutionary perspective, this substance is found as far back as 350 million years ago,” he says.

This suggests it has quite a useful function, says Skjellegrind.

“Experiments show that nerve cells produce more of it when exposed to infections, and it has antimicrobial properties. You can imagine that beta-amyloid acts as a sort of primitive immune defence in the brain. It hasn't had any major negative consequences until we began living as long as we do today,” he says.

Is the herpes virus involved?

Håvard Kjesbu Skjellegrind and his colleagues are now working on a study based on data from the HUNT Study. They aim to explore whether infections play a role in the development of Alzheimer's disease or other brain diseases.

“One of the hypotheses in this area is that the herpes virus family is involved. These are viruses that cause cold sores, chickenpox, mononucleosis, and other relatively common infections. What’s special about the herpes viruses is that they result in a lifelong infection. Even though you get sick from it only once, the virus is still in the body,” says Skjellegrind.

The concern is that these viruses might reactivate in later life, impacting brain health.

Yet, the prevalence of these viruses exceeds the incidence of Alzheimer's, indicating additional factors at play.

“We need to figure this out, as these are infections against which it’s possible to develop vaccines, and for some of them, vaccines already exist. We also have medications that can suppress the infections,” says Skjellegrind.

“If infections play a significant role, then it’s possible to develop both preventative measures and treatments,” he says.

The study is in its early stages and will last for several years, says Skjellegrind. The first results could be ready in a couple of years.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no