This article was produced and financed by University of Bergen

How the potato was brought to Norway

Famine, prohibition and war contributed to the potato’s popularity in the Norwegian kitchen. It all started with the priests.

The potato originated in the Andes in Latin America. They had been growing potatoes for 10,000 years when the first Europeans arrived. These early explorers brought the potato to Europe.

First to Portugal, from where it spread. This was in 1567.

“But it took a while before the potato arrived in Norway, around 1750,” says Kirsti Lothe Jacobsen. She is the Senior Academic Librarian at the Law Library of the University of Bergen (UiB) in Norway. In 2008, when the United Nations declared the International Year of the Potato, she curated an exhibition about the potato’s history in Norway.

The potato priests

Mainly priests and the military, who travelled around Europe and picked up that the potato was both delicious and nutritious, brought the potato to Norway

“The priests grew potatoes in their parsonage, which was the norm in Western Norway in the early days of the potato in Norway. This is how the expression potato priests arose, because they spread the message of the potato from the pulpit,” Lothe Jacobsen says.

This was often their most important message, as there was plenty of scurvy and vitamin C deficiency in Norway at the time. Potato is a great cure for this. In addition, the potato is easily cultivated in Norwegian climate and soil.

“The potato priests knew how important the potato was for the survival of their congregation,” says Lothe Jacobsen.

However, most people at the time did not see it this way.

At risk of leprosy

In the beginning, there was fierce resistance against the potato. Rumour had it that potato eaters were at risk of leprosy.

“The priests gradually convinced people about the merits of the potato,” Lothe Jacobsen says.

But it was only during the Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th century that the potato got fully integrated in the Norwegian diet.

The British navy blocked the seas around Norway, which led to reduced grain imports from Denmark – and a subsequent famine. The people learned that they could grow potatoes instead.

“The Norwegians love affair with the potato was born,” says Lothe Jacobsen.

Alcohol and war

Not the least when it turned out potato was excellent for producing alcohol.

In 1816, the Norwegian parliament, The Storting, passed a law prohibiting the production of liquors – except for grain-based variants. This lead to a flourishing of potato cultivation.

Then, during World War II, the potato once again saved many people,

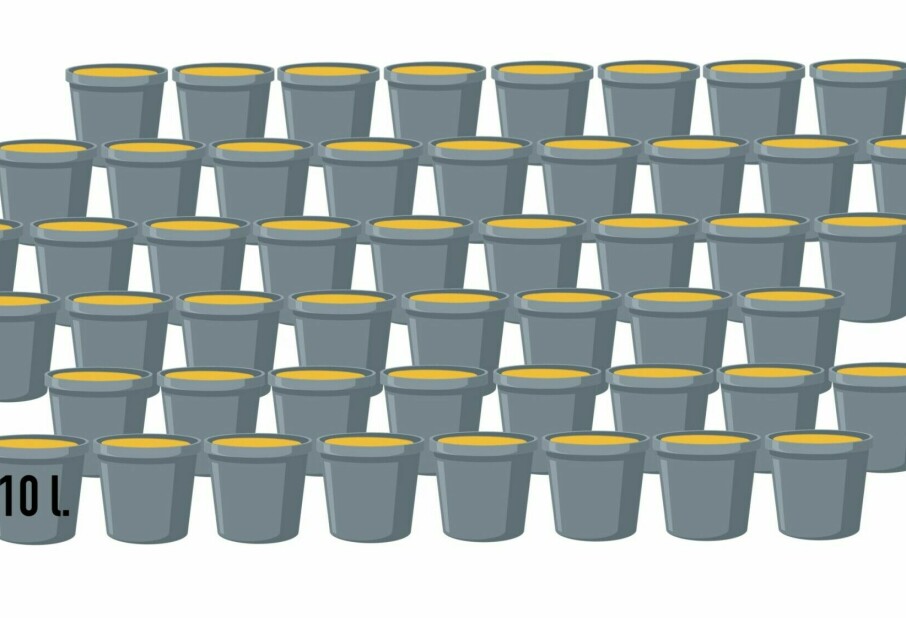

“During the war, most people used their gardens for potato cultivation. Those who didn’t have a garden cultivated potatoes indoors, using pots and pans,” Lothe Jacobsen says.

The potato in the future

Today, the potato fights it out with modern imports, such as rice or pasta, in the shopping aisles. Some nutrition experts have also made the potato the villain in the fight against obesity.

Norwegians do eat far less potatoes now than in the past. In 1959, the average Norwegian consumed about 88 kilos of potatoes a year. By 2007, this number had fallen to 22 kilo annually per person.

“Personally, I believe that the potato will always remain a staple of the Norwegian diet. If another food crisis occurs in the future, I believe that the potato will always come to the rescue and ensure the health and wellbeing of Norwegians,” concludes Lothe Jacobsen.

Translated by: Sverre Ole Drønen