Fungi and rust can stifle smell of slurry

New study shows how fungal spores and rust can help reduce the stench of slurry in biofilters, which help prevent harmful substances from being released into the atmosphere.

Few things can ruin a beautiful spring day in the countryside like the horrid smell of slurry. Imagine living on a farm where the slurry is stored inside a barn and the smell of rotten eggs and other foul substances is flowing past your house every time the ventilation is put on. Probably not a very attractive thought.

To combat such scenarios, some farmers have set up biofilters to prevent the release of harmful substances such as ammonia and sulphur compounds, both of which contribute to the characteristic rotten-egg smell of slurry. Here, the air from the ventilation is led through the biofilter, where bacteria that grow on the filter make contact with the foul-smelling substances and absorb them.

“But not all biofilters are equally good at removing the smelly sulphur compounds from the air. This variation in quality was the starting point of our project. We wanted to find out what it is that makes the filters work, and what does not,” says Claus Lunde Pedersen, who recently defended his PhD thesis ‘Function and structure of biofilters removing sulfur gasses’ at Aarhus University’s Department of Bioscience.

Fungi stifle smell

A Biofilter consists of a material which creates a breeding ground for bacteria. The live bacteria that grow on the filter intercept the harmful substances in the air and convert them. Hence the name biofilter.

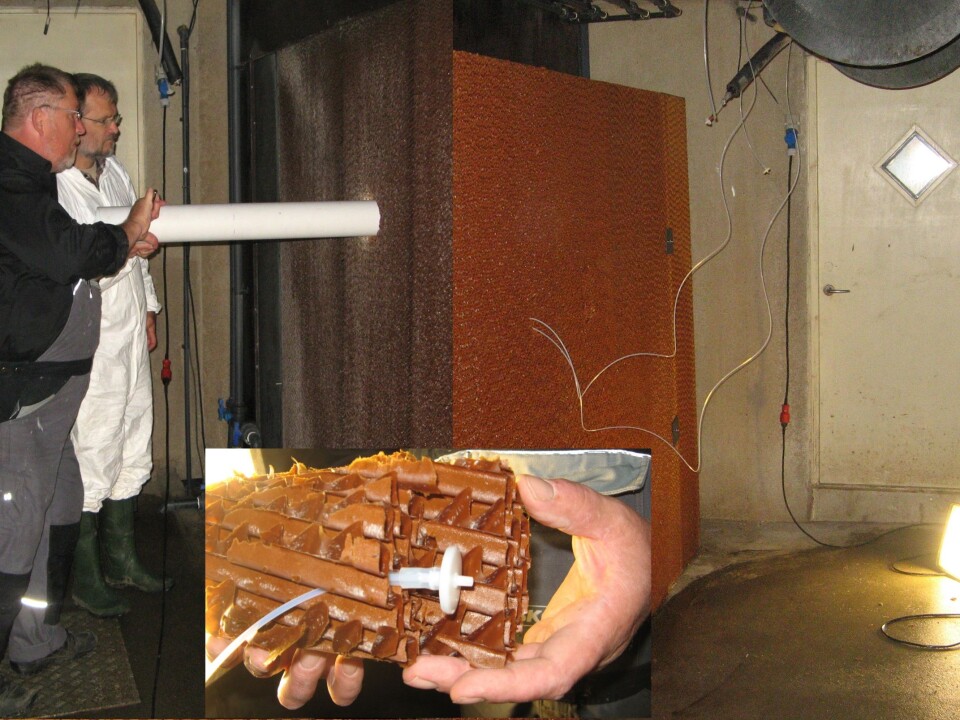

Pedersen has looked at two types of biofilters:

- One in which cellulose is used to create an environment where the bacteria can grow (see picture 1)

- One in which small clay pellets, the so-called LECA nuts, make up the framework for bacterial growth (see picture 2).

The primary task of a biofilter consists of removing the harmful ammonia that is produced in pigs’ faeces when they are in the barn. The filters are good at removing ammonia, but other, less harmful, sulphur compounds are also formed in the slurry. These are the real culprits when it comes to smelly slurry, and they are not as easily removed by the biofilters.

“We carried out chemical analyses of filters in various stables,” says Pedersen. “We noticed that in some cases the filters worked very well and in addition to removing the ammonia, they removed 80 percent of the sulphur compounds, but in other cases they passed through the filters. The source of the differences in the case of the cellulose filters turned out to be the fungi that grow on the surface of the filters.”

Hairy mould removes the stench

This film of bacteria on the surface of the cellulose filters causes mould. Mould is composed of fungi and looks like a white, hairy coating. And it is actually in this furry appearance that the key to how the biofilters work can be found.

The furry appearance is a result of the fungal hyphae ‘standing up’ on the surface. These hyphae function as a launch pad for the fungal spores that the fungi spread around them, and therefore can only be traced periodically.

“We demonstrated with experiments and observations that there is a correlation between the fungal hyphae being visible and the filters absorbing the sulphur compounds and clearing the air of odours in the most effective way,” says Pedersen.

This new finding may be useful in further research and in practice if it helps scientists create an environment in which the fungi remain in a phase where they spread spores and their hyphae are erect.

The iron in clay pellets remove smell

We demonstrated with experiments and observations that there is a correlation between the fungal hyphae being visible and the filters absorbing the sulphur compounds and clearing the air of odours in the most effective way.

The other biofilter that Pederson studied is made up of LECA nuts. These are small clay pellets, probably best known from their use in flower pots. These nuts are used because they have a rough surface that bacteria can easily stick to and grow on.

The red clay colour of the LECA nuts is due to oxidised iron, i.e. iron that has been in contact with oxygen – a process similar to the one that produces rust. It has previously been shown that oxidised iron can react with some of the sulphur compounds and that the iron can thus help remove the smell of slurry.

”We asked ourselves whether the effect of the iron oxides is preserved in the biofilters, or whether the bacteria that grow in the biofilters block the effect,” he says.

"We took some material from a biofilter that had been in use for about a year and had bacteria on its surface, and then we compared it with LECA nuts that had not been used. We observed that the used filter was better at removing sulphur compounds than the unused one.”

This indicates that half of the removal of hydrogen sulphide can be attributed to the LECA nuts and the iron inside them. The bacteria do not limit the function of the iron, but both parts have an effect, It would therefore be a good idea to ensure that there is iron in the materials that we use in our biofilters if we want to get rid of hydrogen sulphide.

This means that the bacteria remove sulphur compounds. To determine whether iron also plays a part, the researcher heated up the material from the used biofilter, thus inactivating the bacteria.

The experiment revealed that the used material without active bacteria removed the smell just as well as the unused filter.

”This indicates that half of the removal of hydrogen sulphide can be attributed to the LECA nuts and the iron inside them. The bacteria do not limit the function of the iron, but both parts have an effect,” he says.

“It would therefore be a good idea to ensure that there is iron in the materials that we use in our biofilters if we want to get rid of hydrogen sulphide.”

Pedersen’s PhD study has identified some of the crucial factors that affect a biofilter’s ability to remove the stench caused by sulphur compounds in slurry, and he hopes his findings will help improve biofilters in the future.

---------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk