Singing bowhead whales give new insight into behaviour

Of the estimated 12 species of baleen whale, only the song of the humpback and bowhead whale covers both low and high frequency areas. A researcher has looked into this mystery.

Over the past seven years, biologist Outi Tervo has made innumerable trips to Greenland’s Disko Bay to study the sound of the ocean.

It is not so much the grinding noises of the icebergs that make the researcher brave the cold; rather, it’s the song of the bowhead whale.

”The bowhead whale is interesting because it has been close to extinction, and because we know so little about it. By analysing its sounds maybe I can learn more about its behaviour, and this includes finding out why it sings. My greatest challenge has been the lack of information about the whale,” says Outi Tervo, project coordinator at the Arctic Station in Disko Bay, Western Greenland.

”No sound recordings were available of the bowhead whale’s song in winter, so it was a challenge at first simply to find the bowhead whale among all the other sounds, seeing as I didn’t really have a frame of reference.”

Increase the pitch and find your mate

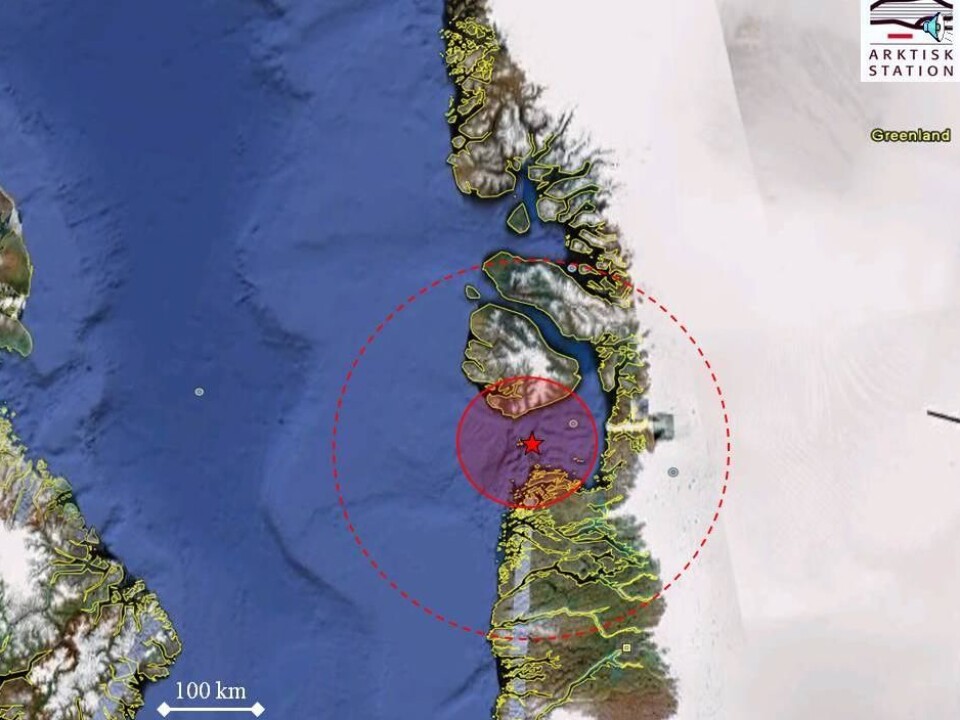

The Arctic Station in Qaqertarsuaq in Disko Bay is an ideal location for observing bowhead whales.

”Here we can record sounds over longer periods than elsewhere. We start when the whales arrive from the other side of the Davis Strait at the end of January and keep going until they disappear again around May,” she says.

”We have observed that their song is very seasonal, both in terms of how it sounds and how much they sing. From being very active in winter, they become virtually silent in May.”

Scientists know from other species of baleen whale and from birds that a complex and high song intensity is often associated with mating. So although the researchers cannot see the whales because of the ice, they assume that something quite social is going on below the ice when the singing activity is high.

In Alaska the whales have their mating season in winter. The great difference in singing activity may be related to the trend in which a declining desire for singing in late spring is replaced by an increased desire for food at this time of year – and this gorging usually occurs in silence. At this time of year, copepods are plentiful, making it easy for the whales to hoard food.

Unprecedented high incidence of females

To determine whether it is the females or the males that do the singing, the researchers needed a sound recording and a biopsy of the whale they believe was singing at that particular time and place.

The researchers managed to obtain 22 biopsies of bowhead whales. But unfortunately only one of these biopsies could be linked with certainty to a singing whale. This biopsy revealed that the whale in question was a female.

Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen, a senior researcher at the Greenland Institute of Natural resources, has data sets that are not linked to individual singing whales. But they show that some 80 percent of the bowhead whales in Disko Bay are female. Some of Tervo’s data points in the same direction.

We know of no other Arctic areas that have meeting places predominantly for females.

“This is unheard of. We know of no other Arctic areas that have meeting places predominantly for females,” she says.

Males hide away in Disko Bay

One explanation of the high incidence of females could be that the male population has been largely wiped out. But this theory has been rejected by Mikkel Sinding, a master's student at the Centre of GeoGenetics, Natural History Museum of Denmark, whose DNA analyses revealed that the high incidence of females goes a long way back into history.

In a recent article, Tervo suggested that the acoustic signals co-evolved with the whales’ collective behaviour.

The bowhead whale has the special ability to emit sounds covering a very broad spectrum between approx. 20 and 4,000 Hz. Tervo believes that these two extremes have separate evolutionary purposes:

My theory is that the low-frequency sounds are used as a ‘here I am’ signal to cover great distances. The high-frequency sounds, on the other hand, are used locally to say something about the whale’s identity and position, and can help the recipient to zoom in on the sender.

”With such a broad frequency range, the bowhead whale can pack a lot of information into its song,” she says.”My theory is that the low-frequency sounds are used as a ‘here I am’ signal to cover great distances. The high-frequency sounds, on the other hand, are used locally to say something about the whale’s identity and position, and can help the recipient to zoom in on the sender.”

In other words, the females’ accumulation in Disko Bay is a form of supplement or compensation for the limited reach of the bowhead whale’s high-frequency song. The fact that precisely Disko Bay has become the place for females to accumulate is probably not a coincidence either.

The bay is very rich in food – and that is much appreciated by the female whales after all the physical strain of mating.

------------------------

(This article is reproduced on this site by kind permission of Polarfronten, a Danish online magazine with news about polar research.)

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther