Fish migrate to avoid predators

Tagged fish reveal that animals migrate to avoid being eaten by predators.

Many fish migrate from lakes out into the neighbouring streams in winter. Here they wait until the weather conditions improve, so they can swim back into the lake.

Up to now, scientists have only had theoretic explanations of this behaviour.

A new study now shows that fish that migrate out into the streams are less likely to be eaten by predators than fish that remain in the lake. This suggests that winter migration has been developed as an adaption against predation.

This behaviour is not limited to fish and could very well apply universally to animals.

”Roach and other cyprinids migrate into the lakes’ adjacent streams in winter, where they are packed together very densely. In combination with other studies, this one shows that roach that migrate out into the streams avoid being eaten by cormorants,” says the lead author of the study, Christian Skov, a senior researcher at DTU Aqua at the Technical University of Denmark.

”This survival mechanism – migrating to avoid predators – could very well explain why many animals, from tiny plankton to large mammals migrate.”

The study, published in the journal Biology Letters, is the result of a Danish-Swedish research partnership.

Thousands of fish with PIT tags

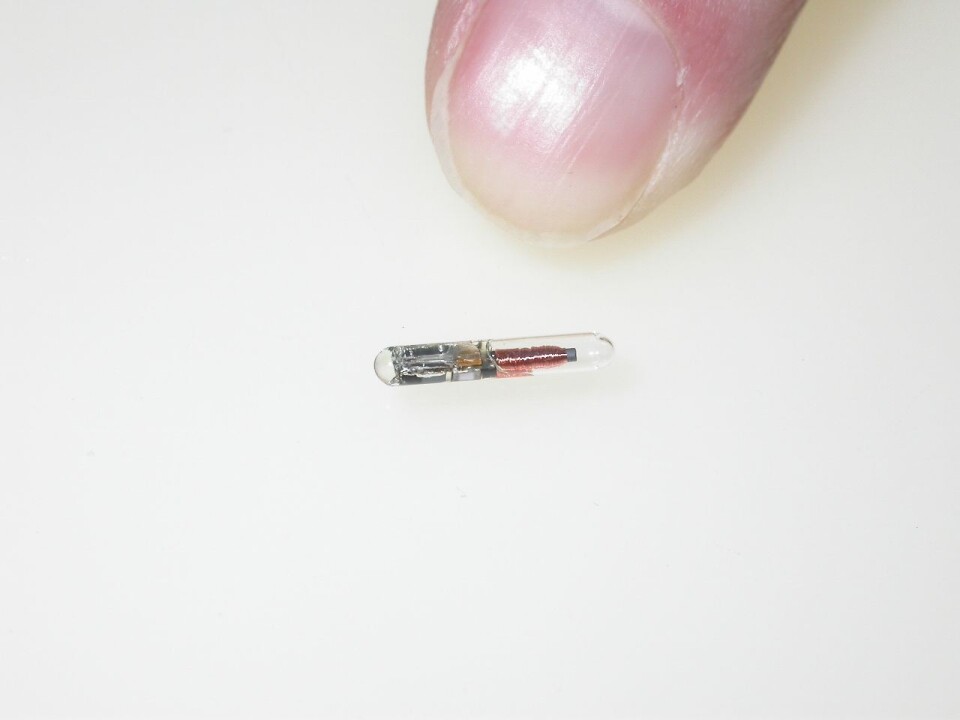

In the study, the researchers fitted small PIT tags (Passive Integrated Transponders) into the abdominal cavity of thousands of roach caught and released in two Danish lakes.

Recorders by the streams running to and from the lakes enabled Skov to monitor how many of the tagged fish stayed in the lake and how many migrated out into the streams.

“With the PIT tags we could create a history for each individual fish,” he says.

“We could see whether it was in the lake or in the stream and how long it stayed in each place. At certain points during the winter, 60 percent of the fish were swimming in the streams, and at some points a full 70 percent were in the streams.”

Birds snatched the fish

However, not all the fish survived the research process. Some of the roach were eaten by cormorants from a nearby cormorant colony.

When a PIT-tagged roach had been eaten by a cormorant, the PIT tag eventually re-emerged either through the bird’s cast or through its stool. Using a special scanner designed as a mine detector, the researchers could retrieve the tags in the areas where the cormorants could typically be found, e.g. in breeding colonies.

“It was actually a coincidence that some of my colleagues scanned for our PIT tags near a cormorant colony. Here we found several of our PIT tags. We then set out to examine whether there was a correlation between which fish had been eaten and how long they had stayed in the streams,” says Skov.

Streams boost chances of surviving

Their analysis showed that the cormorants had mostly eaten fish that had not migrated out to the streams.

This suggests that migrating to the streams in winter greatly improved the odds of surviving.

This survival mechanism – migrating to avoid predators – could very well explain why many animals, from tiny plankton to large mammals migrate.

“Our analysis of the individual history of the eaten fish showed that the less time they spent in the lakes, the lower their risk of being eaten. This is consistent with the idea that the cormorants only catch fish in the lake and not in the adjacent streams, which in these water systems are probably too small for the cormorants to hunt effectively.”

Why don’t all the fish migrate?

It may seem a bit odd that not all the fish migrate to the streams in winter. Some of them remain in the lakes, even though this presents a greater risk of being eaten.

According to Skov, this is related to the cost of swimming in the streams.

In summer, when the water is warm, the fish grow and need a lot of food, and this food is only available in the lakes.

In winter, when the water is cold, the fish do not grow anywhere near as much, and their food requirements are lower. This is why they can migrate into the streams – but here the food is scarce.

“The roach can survive the winter in the streams thanks to the fat deposits they have accumulated over the summer. This is how they avoid being eaten in the summer months by staying out of the lakes. But not all the fish are fat enough to survive an entire winter without food, which is why they need to go back to the lake in search of food. Here there is a risk that they will be eaten. But this is probably something they have to do to survive,” says the researcher.

”Our study is the first of its kind to directly quantify a predator avoidance benefit to migrants in the field. It also substantiates a link between migration and the threat from predators. Numerous existing theories point in this direction, but they have so far not been proven in ‘the field’.”

------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther