Toothless in Sweden no more

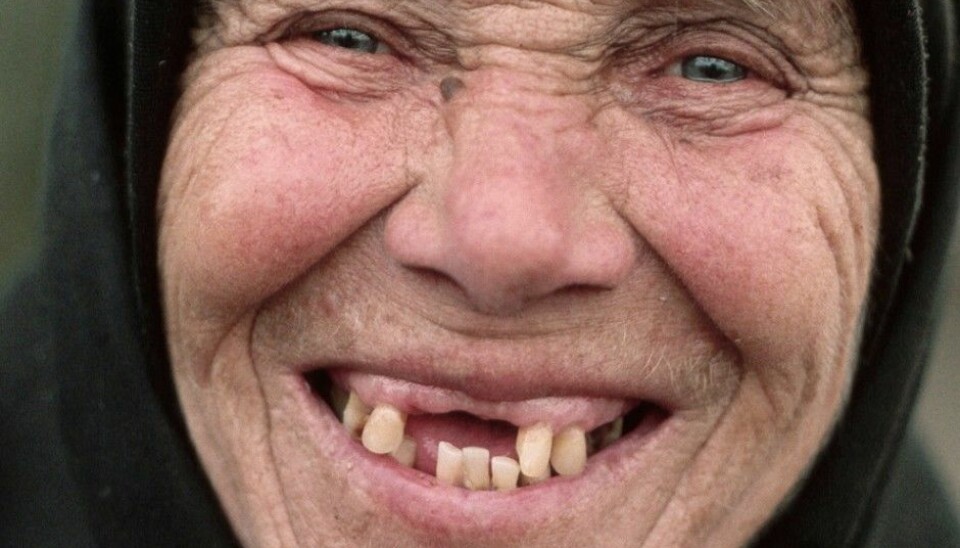

Dental health in Sweden has improved radically over the last four decades, with just a tiny fraction of 50-year-old women toothless in 2004.

In 1968, roughly 20 per cent of all 50-year-old Swedish women were toothless.

Over the ensuing years, however, dental health in Sweden improved dramatically, according to Anette Wennström, a Swedish dentist. By 2004, most middle-aged Swedish women could smile with their own teeth, the beneficiaries of fluoride use and progressive dental health programmes. Just 0.3 per cent of 50-year-old Swedish women in 2004 had no teeth, Wennström found.

Wennström used data from the Population Study of Women in Gothenburg, Sweden, which started tracking dental health among other factors in 1968, to examine these trends. She also looked at the larger issue of how dental health reflects overall quality of life and health for her PhD dissertation at The Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg. Her research showed in part that middle-aged women with more education had much better dental health than less well-educated women.

Lack of studies in European countries

It turns out that the Swedes are nearly alone in Europe in having good solid data on dental health. A 2007 study conducted by Swiss researchers found that many countries in Europe lack sound epidemiological studies on tooth loss.

That matters because of the clear links that have been shown between oral health and other types of diseases, says Kristin Klock, a community odontologist and professor in the Department of Clinical Dentistry at the University of Bergen.

Klock herself looked at tooth loss in Norway for her own dissertation, finding that self-reported tooth loss among Norwegians was on par with other industrialized countries. And much like Sweden, there were socioeconomic differences: Individuals with more education kept their teeth longer than less well-educated individuals, she found.

But that is where the similarity between Sweden and Norway ends, Klock believes.

Who pays for dental care matters

One important distinction between the two Scandinavian countries concerns funding. In Norway, children receive free dental care up to age 18, but afterwards, the patient must pay his or her own dental costs, with some exceptions. In Sweden, there is a ceiling on how much the patient has to pay out of pocket. Once dental expenses surpass this ceiling, the government covers the rest.

This difference might lead to the presumption that dental health in Norway is worse than in Sweden. But Klock says the differences in payment systems might actually encourage better dental health in Norway.

Norwegians “might put more of an emphasis on prevention because of the out-of-pocket costs, compared to the Swedes,” she said. “The more fillings you get, the more likely it is that you eventually have to remove the tooth.”

The problem is, however, that there is little information for researchers to use to draw conclusions on dental health and financing policies, Klock says.

“We know almost nothing about how the different financial mechanisms work,” she said. “This is certainly something we need to know more about.”

Heart disease links

Several studies have shown a link between bacteria in the oral cavity and the risk of atherosclerosis.

A study from Uppsala University published in mid-December 2015 shows that patients with coronary heart disease who do not have teeth have nearly double the risk of death as those who have all their teeth intact. The study was conducted with data from more than 15,000 patients from 39 countries.

“The risk increase was linear, with the highest risk in those with no remaining teeth,” said lead author Dr Ola Vedin, a cardiologist at Uppsala University Hospital and Uppsala Clinical Research Center, in a press release from when the paper was published. “For example, the risks of cardiovascular death and all-cause death were almost double to those with all teeth remaining. Heart disease and gum disease share many risk factors such as smoking and diabetes but we adjusted for these in our analysis and found a seemingly independent relationship between the two conditions.”

Vedin said that they had plenty of data to work with, which makes their findings robust.

“Many patients in the study had lost teeth so we are not talking about a few individuals here,” Vedin said in the press release. “Around 16% of patients had no teeth and roughly 40% were missing half of their teeth.”

Gum disease is one of the commonest causes of tooth loss. Poor dental hygiene is one of the strongest risk factors for gum disease. Inflamed gums can trigger atherosclerosis, the Uppsala researchers believe.

However, the Uppsala study is only an observational study, which means that researchers cannot conclude that gum disease leads directly to heart problems, even if they find a correlation.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no