Tomorrow's technology will lead to sweeping changes in society – it must, for all our sakes

OPINION: The shift to tomorrow's society will not take place over hundreds of years, but within a generation, argue two researchers.

Throughout history, whenever new technologies have emerged that change our means of production and ability to communicate they have tended to transform society. The rapid technological development of the past century – in biotechnology, information technology, nanotechnology and artificial intelligence – holds the promise to do the same for our current, post-industrial world.

Our political institutions, the rule of law, human rights, the banking system, our education system – and even capitalism itself – are products of the industrial age. We have learnt to navigate the industrial economy as individuals, and as societies we can exert some control to define its shape and limits.

But what comes next, in a post-industrial world? Even in the past decade, digital products and services, the internet and mobile technology have changed our lives. This is the result of accumulated advances over the past 50 years; there is much more to come. For example, recent studies indicate that digitisation is likely to replace about half of known jobs within 20 years.

Tomorrow’s technology

In the industrial economy, more was better – but now this is not always the case. The developed world is sick from overeating, while greater productivity leads to cheaper goods and greater consumption, which squanders Earth’s resources ever faster and fosters a wasteful, consumption-based economy. Instead, a future economy would strive to provide a world of plenty, with virtually no waste.

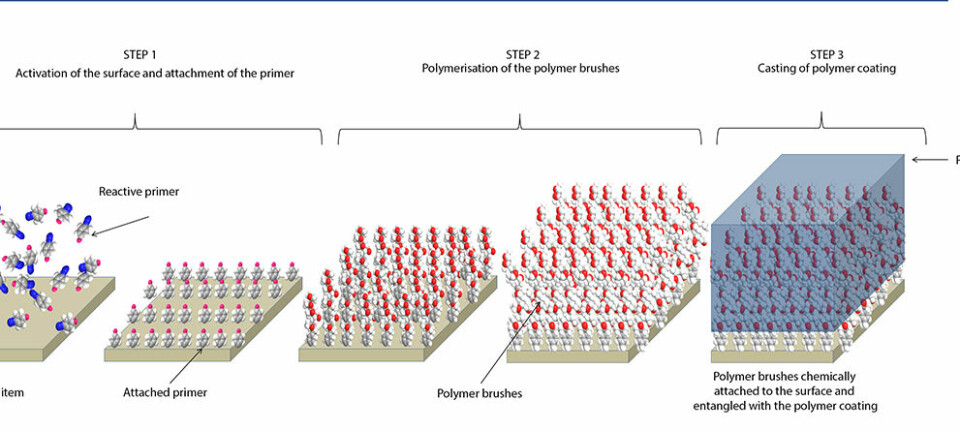

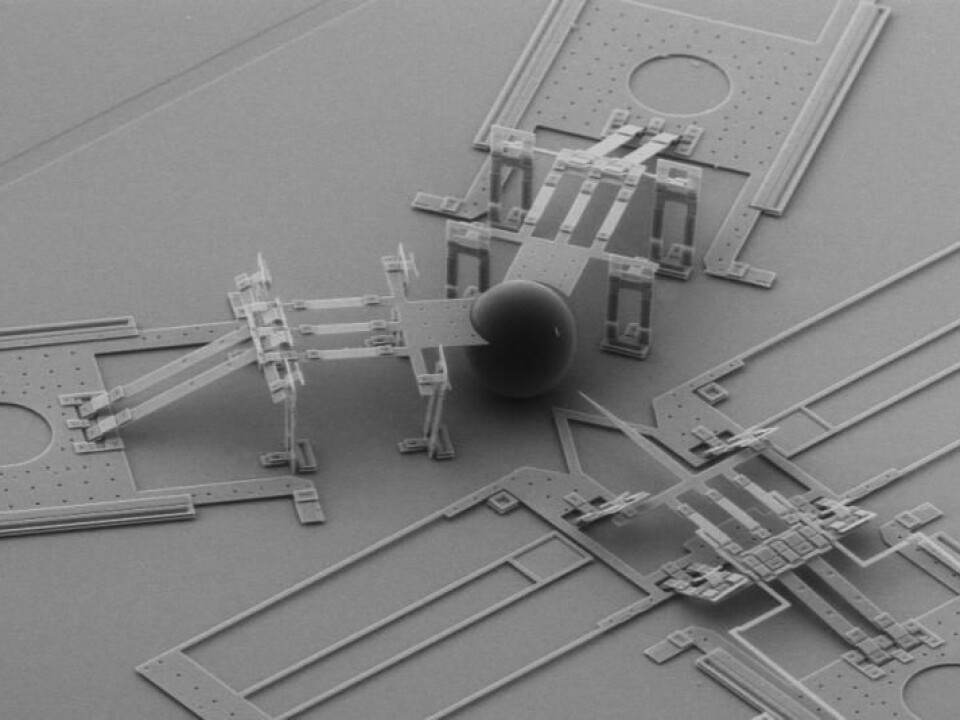

It is the convergence of cutting-edge biotech, infotech, nanotech, and cognitive sciences (BINC) that will be at the heart of the living and intelligent technologies of tomorrow

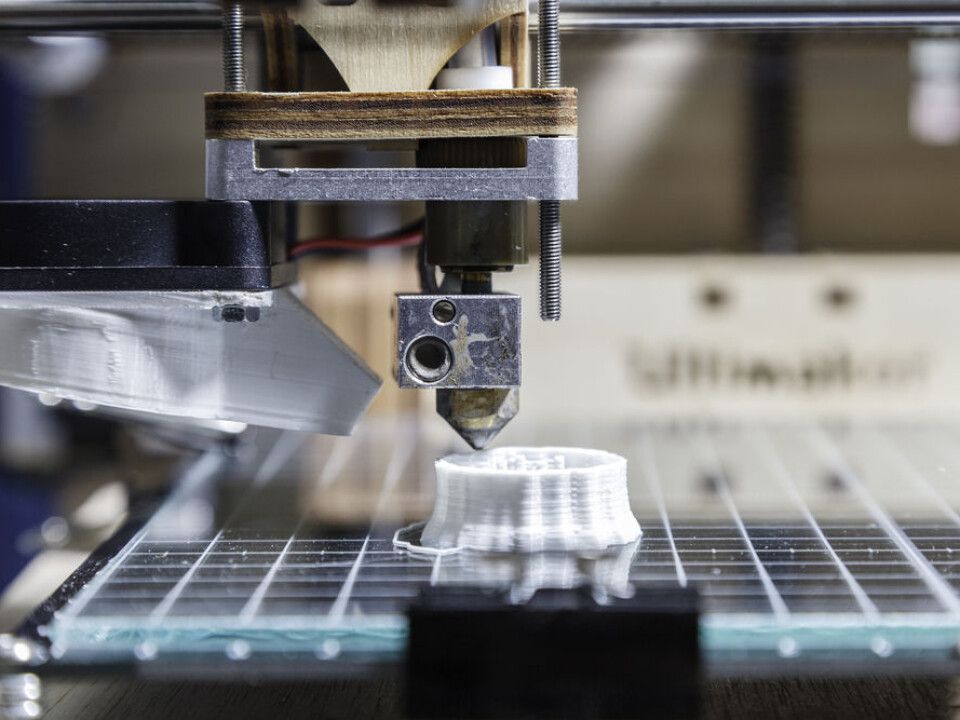

As technology becomes more lifelike more components can be recycled, in the same way that materials are within biological systems. Thanks to automation, only a small percentage of the population will be needed to produce and distribute what everybody needs. For example, today only about 2% of the Danish population is engaged in agriculture and fishery, down from almost everybody some 150 years ago – and these 2% can feed several countries the size of Denmark. With the development of personal fabricators – super-advanced 3D-printers – it’s likely citizens will be able to design, manufacture and recycle pretty much everything they need at home.

The BINC technologies are likely to lead to big changes in society, just as computerisation has been the driving force for the past 50 years. This could be as drastic as the differences between the Stone Age and the Bronze Age, or from agricultural society to the scientific age of industry. Inevitably, such a shift leads to changes in economic and political systems, national sovereignty, balances of power, the environment, the human condition, even religion. But this time the changes will not take place over hundreds of years, but within a generation or so.

Four steps to change

What is bringing about this change now? We believe four interacting patterns indicate what is underway.

1. A digital economy

The digital economy is fundamentally different. Digital products and services account for an increasing part of the economy, yet only the first unit requires capital and labour – subsequent digital copies are practically free of cost. Such digitisation and automation removes more jobs than it creates, driving demand for highly skilled individuals and competition for scarcer middle and low-grade jobs. With virtually none of the transportation costs you would get with physical products, on the internet such products are immediately global, and the best product takes all – look at the dominance of Facebook, Google, and Microsoft over their rivals.

2. An eroding middle-class and democracy

As recently documented by Thomas Piketty, the erosion of the middle-class in all developed economies. The gap between the middle-class and the super-rich widens, concentrating wealth and political power among the elites. In today’s financial economy there is greater return on investment in speculation than in production; being rich is a surer path to wealth than working.

With about half of middle-class jobs disappearing, nation states will lose much of their tax revenue. Unless we radically rethink taxation, this will fundamentally change the economic foundation upon which democratic states are governed.

As economic and political elites converge, political power is concentrated in progressively fewer hands. This power grab is supported by the information infrastructure, through which citizens' personal data can be monitored and accessed, eroding privacy, civil and democratic rights.

3. One world

Global challenges are beyond the powers of individual nations. For example, the CO2 generated in one country affects the entire planet; there is only one environment – and the transition to a sustainable energy system must be a global one.

As information, people and capital travel with increasing freedom around the world, the planet is gradually redefined from some 200 national economies to one global economy, for which there is no common law. Businesses can re-home themselves in low or no-tax states – this leads to a race to the bottom with competing nations cutting corporate tax rates even as income tax revenues dwindle. Single states will no longer be able to take care of their citizens alone.

As nations become more interconnected, this will also lead to difficulties in how to align their often radically different economic, cultural and governmental structures – for example between traditional Arabic, industrial Russian and modern, digitised Scandinavian.

4. The need for new narratives

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the struggle between capital and workers play out across the left-right political spectrum, but today this distinction is weak. In the West there is some broad agreement based around a vision of the open society, a liberal democracy, market economy and public welfare. But in other regions of the world, any such broad agreement is around different, even contradictory concepts.

Technological change is so rapid that it has out-stripped political and legal frameworks, changing the way the economy or even society works before the law can catch up. The converging BINC technologies will accelerate this process into something we have difficulty imagining. And as yet there are no global institutions that can handle this transformation.

The grand narratives which used to keep societies together – religion, nation and class – are losing their power to guide and explain the world, and are sometimes used for the support of totalitarian regimes. In fact the only grand narrative that has survived is “the free market”: it can provide consumer goods efficiently, but it is incapable of solving any of our current problems. If anything, it fuels them.

The new BINC age

So to create sustainable economies, preserve human dignity and avoid social conflict, these issues must be at the forefront of our national and international politics. In a world in which knowledge is viewed as an indisputable asset, we must put it to work to understand this global transformation and develop sustainable paths for the future. Continuing to cling to the belief that only free markets and nation states will resolve our current dilemmas is naïve. We need to recognise reality as it is – not as it once was.

With the right political, legal and economic structures and institutions in place, the convergence of BINC technologies can promise meaningful work, leisure time, prosperity and freedom for all. Conversely, apathy and avarice could see this transition bring our world into a new dark age, a dystopia controlled by a tiny elite.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article here.

![]() Lene Rachel Andersen receives funding from University of Southern Denmark and Next Scandinavia.

Lene Rachel Andersen receives funding from University of Southern Denmark and Next Scandinavia.

Steen Rasmussen receives or has received funding from the European Commission, the Danish National Science Foundation and the University of Southern Denmark.