Raw fish gave the Vikings tapeworms

“I’ve never thought about how they prepared their food – or didn’t,” says archaeologist.

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, stomach pains, and weight loss.

Tapeworms were a common complaint among the Vikings and people across Europe up until as recently as the middle of the 20th century.

A new study shows that in many cases, these parasites came from eating raw fish and pork.

Most people would have had mild symptoms, but in the worst cases the fish tapeworm would have led to blood loss, while the pork tapeworm could lead to seizures.

“If you cook or fry the meat properly then you won’t be infected by the parasite, so it indicates that these people were eating raw or poorly cooked meat,” says Martin Søe, who conducted the work while employed at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Read More: How to decorate like a Viking

New method reveals ancient diet

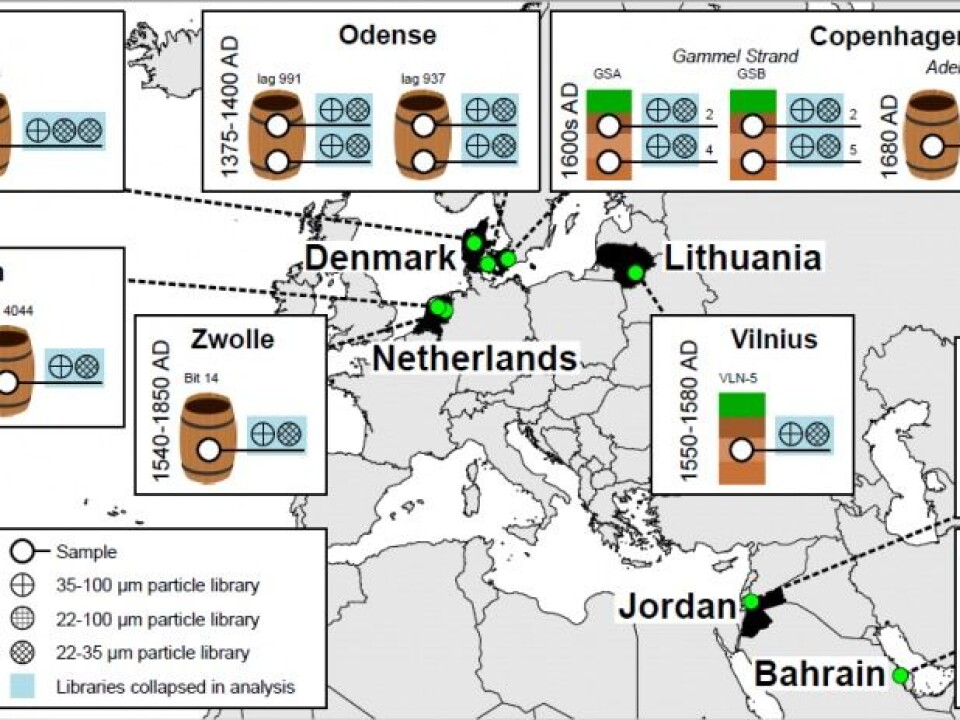

Søe is the lead-author on the new study in which he and his colleagues analysed excrement from ancient latrines around Europe and the Middle East.

He was also part of the research team who in 2014 showed that Vikings were plagued by parasites. In the new study, they used more advanced methods to analyse the DNA of latrine samples and identify the parasites.

The study began at the Viking site at Viborg, Denmark, and expanded to a number of other sites in Denmark and beyond. The samples cover a period from 500 BCE up to the 18th century.

Read More: Vikings versus Iron Age: Who made the best swords?

DNA extracted from ancient human excrement

The scientists studied parasitic eggs extracted from excrement preserved in ancient latrines. These latrines would have been used by numerous peoples and hygiene would have been very poor by today’s standards.

They sequenced the genomes of each sample using a method known as ‘shotgun sequencing,’ which is adapted to analyse old, often broken, samples of DNA.

“We applied the newest DNA techniques. At the normal microscopic level, you can’t see which species the parasite comes from, but we can with DNA. This means that we can see more details than we could previously,” says Søe.

Read More: Did Vikings really fight behind a shield wall?

New source of information

Using the shotgun method, Søe and colleagues could differentiate between the parasites that infect humans and those that infect animals.

They discovered that samples from all time periods contained the giant roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides) and the human whipworm (Trichuris trichiura). These worms infect humans, and were found in samples from 500 BCE Bahrain to 19th century Holland (Zwolle, 1540 to 1850 CE).

The scientists identified parasites that must have originated from sheep, horses, dogs, pigs, and rodents. This indicates that humans must have lived in close quarters with animals.

At the Viking site at Viborg, they found DNA from fin whales and deer, indicating that Vikings had hunted these animals for food.

Many of them were plagued by tapeworms, which were found at sites from the Viking Age and right up to the 19th century.

The analyses show that people in 17th century Denmark must have eaten a lot of saltwater fish, including cod. Pork was also a source of tapeworms at the Danish sites.

This level of detail in the study would not have been possible with standard microscopy, says archaeologist Peter Hambro Mikkelsen, head of the Department of Archaeological Science and Conservation at Moesgaard Museum, Denmark.

“It gives us a new source of information. It’s interesting in cases where we, for example, lack animal bones and the only witness we have as to their condition are parasites,” says Mikkelsen.

Read More: DNA study: Vikings were plagued by intestinal parasites

New DNA analyses indicate how meals were prepared

Some of the sites samples are new excavations, such as the site in Copenhagen, Denmark, which was uncovered and investigated during the expansion of the Copenhagen metro.

Other samples came from older archaeological sites, like the Viking settlement at Viborg.

Archaeologists knew from these samples that the Vikings had eaten a diet of fish and pork. But the new DNA analyses go a step further and indicate how the food might have been prepared.

“We found bones from both pigs, fish, and smelt, which is a small salmon that spawns each spring around 21st April. They do this today and they did so 1,000 years ago. So, we knew that they ate fish and pork, but I never thought about how they prepared their food – or didn’t prepare it,” says museum curator Jesper Hjermind from Viborg Museum who led the Viborg excavation in 2000.

Read More: 1,000-year-old Viking toilet uncovered in Denmark

Large potential of parasites

Environmental archaeologist Marcello Mannino from the department of Archaeology and Cultural Studies at Aarhus University, Denmark, describes the new results as a useful contribution to the archaeology.

“People should do more of this type of work, because it can tell us a lot about the dietary habits and living conditions of city dwellers,” says Mannino.

According to Mannino, studying parasites and eggs in combination with traditional archaeological techniques, has huge potential. Especially in Denmark and Scandinavia, where they are so well preserved.

“In combination with other archaeological sources, the genetic identification of parasite remains can provide us with much useful information,” he says.

The new study is published in the scientific journal PLOS One.

----------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article at Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex