Plastic waste from Europe and USA ends up in the Arctic

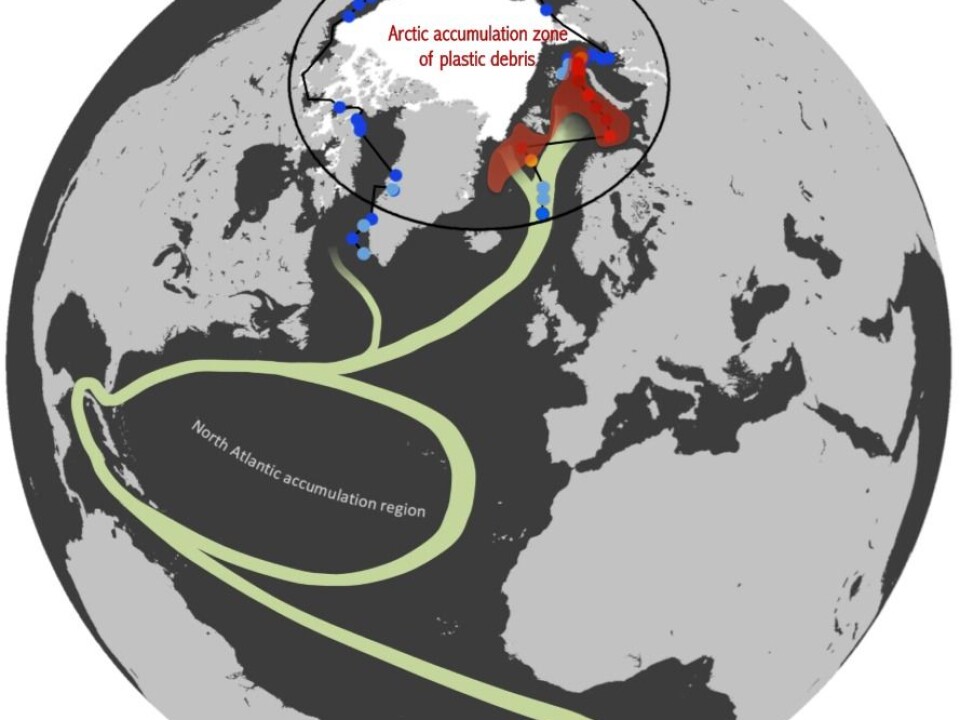

In just a few decades, the Arctic Ocean has become a dumping ground for plastic waste from the USA and Northwest Europe, shows a new study. Over time, plastics from as far away as China could also reach the Arctic.

The seas north of Norway and to the east of Greenland are a dead end, a one-way street, for the plastic waste created by communities along the east coast USA, UK, Scandinavia, and the rest of Northwest Europe.

Our plastic waste in transported by ocean currents up to the Arctic Ocean, where it can affect the sensitive Arctic ecosystem, with knock on effects for us humans as the area is home to large fisheries.

These are the findings of a large research collaboration between twelve institutions from eight countries.

“We found that the Barents Sea is the terminal site for ocean plastic pollution, with high loads also encountered in the Greenland Sea,” says co-author Carlos Duarte, a professor in marine biology at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, and the Arctic Research Center at Aarhus University, Denmark.

“It happens to be also the site of one of the most productive cod fisheries in the world. So the concern is that plastic accumulated there could enter the food web, to which humans are linked via fisheries. Other animals can also ingest the plastic, particularly sea birds, which are very abundant in the Arctic,” he says.

The new results are published in the journal Science Advances and are the last piece in the puzzle that now completes the global map of plastic pollution in the ocean.

Read More: Microplastics in the earth: A reason to worry?

Plastics come from ships and coastal cities

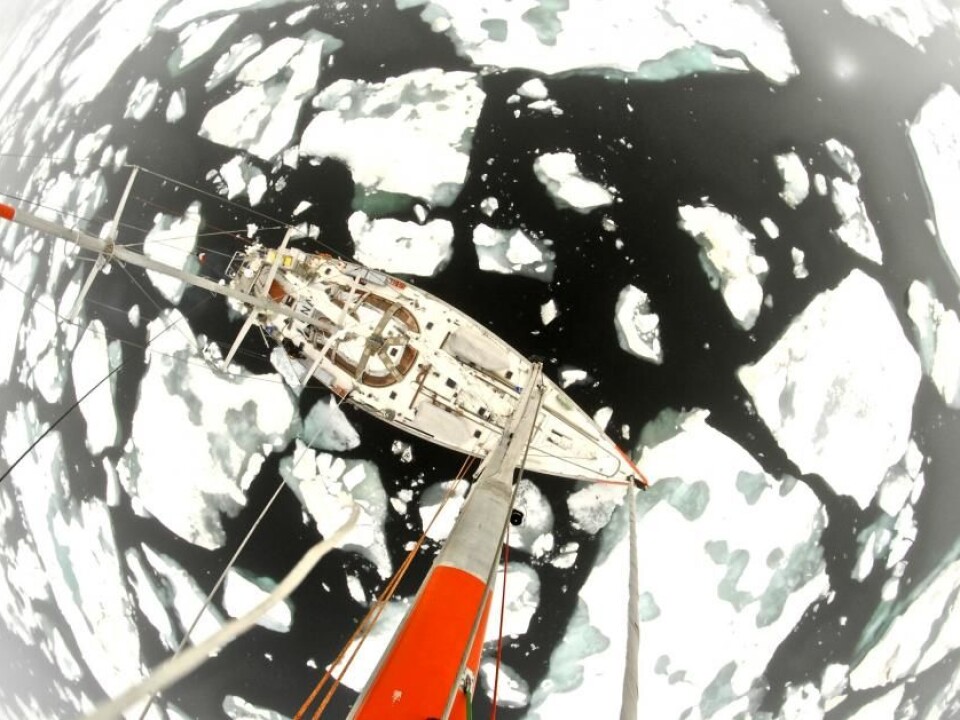

Scientists collected and analysed some of this plastic waste during a five-month-long cruise of the Arctic Ocean and compared this with plastics collected during similar studies in oceans and seas around the world.

They discovered that most of the plastic waste that had collected in the Arctic Ocean was not local and must have come from far away.

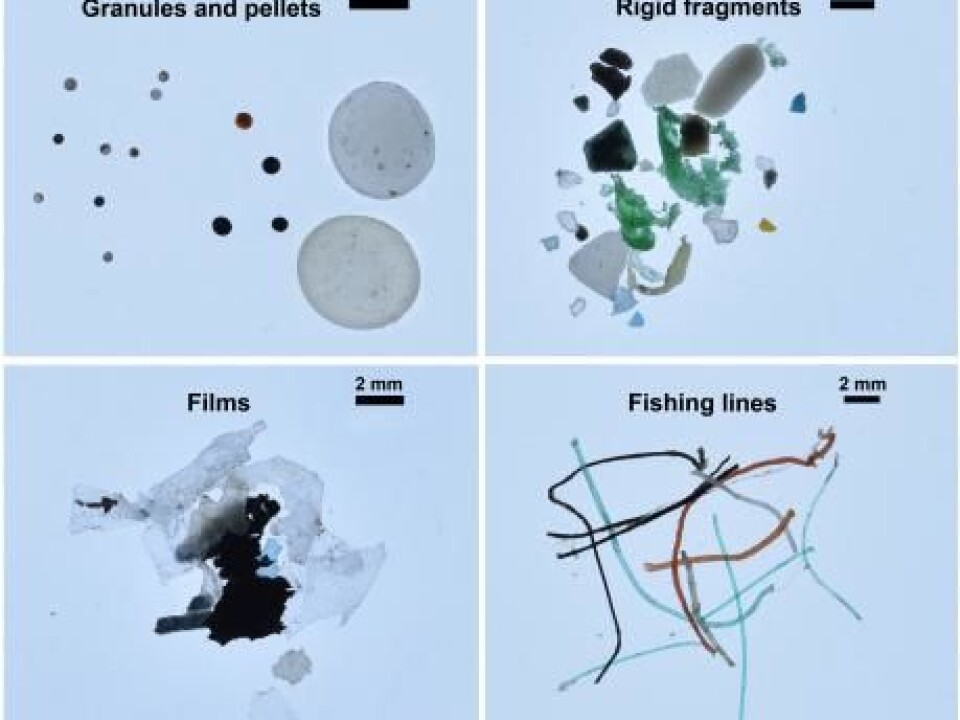

The Arctic Ocean is surround by a sparsely populated coastline and the biggest local source of plastic is fishing nets from commercial fisheries. If the plastic had come from local sources in the Arctic then the scientist’s samples would be dominated by this type of plastic. Instead, they were dominated by plastic waste from towns and cities.

The scientists compared their data with models of ocean circulation and 17,000 satellite-tracked buoys in the Atlantic Ocean to trace the source of the plastic to eastern USA, UK, Scandinavia, and the rest of Northwest Europe.

“Our first idea was that the high plastic areas corresponded to the area supporting the highest fishing activity, suggesting fishing activity was responsible for much of the release. However, if that had been the case, this plastic would have been dominated by fishing line, which was a minor item in the Arctic pool of microplastic,” says Duarte.

“Hence, the plastic accumulated there may have been transported after entering the ocean along the main shipping lines across the Atlantic, or in major cities along the Atlantic coasts of Europe and North America,” he says.

It is likely that plastics from even further away are already making their way to the Atlantic, and from there, the Arctic Ocean, says Duarte.

“Plastic released from cities even further away, all the way to India and China, may eventually reach the Arctic. But this involves very long transport times,” he says.

Read More: Nine of ten fulmars have plastic in their stomachs

An “incredibly interesting study”

Oceanographer and sea ice expert Laura de Steur from the Norwegian Polar Institute is impressed with the new results. She was not involved in the study.

“It’s an incredibly interesting study that combines many different methods and looks at ocean currents across the world’s oceans, which is very important. It clearly shows that the plastic discarded into the oceans around the world do not stay in the local area, but show up in the Arctic and harm the environment there,” she says.

We have long known how pollution in the atmosphere can be transported away from its source, and now we have clear evidence that the same also happens with plastic pollution in the ocean, she says.

Read More: Rubbish found in the deepest ocean depths

Plastic probably ends up at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean

The scientists behind the new study assume that much of the plastic that accumulates in the Greenland and Barents Seas is likely to sink to the sea floor, as it is here that the global conveyor belt of ocean currents sink to the deep ocean, carrying the plastic waste with them.

This may at first sound like a good thing, as the plastic is buried in the deep ocean, away from the rest of the world. But it is not quite that simple, says de Steur.

“The Arctic is an incredibly sensitive environment. Earlier studies have shown lots of plastics in animals and birds in the Arctic, and the plastic affects the ecosystem much more here than at lower latitudes. Also, sea ice makes it logistically more difficult and expensive to clean up than elsewhere on the planet,” she says.

Once at the sea floor, plastic takes a much longer time to degrade due to the cold temperatures and lack of sunlight.

Read More: Top four ocean threats according to marine scientists

Up to 1,200 tons of plastic in the Arctic

Professor Torkel Gissel Nielsen, an oceanographer from the Section for Oceans and Arctic at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), describes the new study as thorough and well-documented. He was not involved in the new study.

“It’s an area of research characterised by emotions and few facts, so there’s a need for a study like this that has actually measured how much plastic there is, and where it’s found. Now we know that there’s quite a significant amount of plastic in areas where no or few people live,” says Nielsen.

The new study estimates that between 100 and 1,200 tons of plastic has accumulated in the ice-free part of the Greenland Sea and Barents Sea, which is approximately equal to 300 billion pieces of microplastic.

Read More: Scientists spread dubious number on debris in seas

Plastic is toxic to some animals

Nielsen emphasises that we need more studies to know what happens to this plastic pollution at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, and precisely how dangerous it is for animals as well as humans.

“We don’t know what happens at the sea floor. Plastic can build-up at the bottom of the ocean and be buried or eaten by bottom-dwelling animals, and in that way it can be brought back up to the surface through the ecosystem,” he says.

The damage caused by plastics to larger animals like sea turtles is very well-documented. But we now much less about how microplastics can impact on the ocean’s smaller lifeforms, such as zooplankton, larvae, and bivalves, he says.

“On its own, plastic is probably not so dangerous—it’s equivalent to me swallowing a handful of beads that pass through the digestive tract and come out of the body again. But some plastic can have a toxic effect in the sea, so that’s dangerous,” says Nielsen.

Read More: Why are banned chemicals still killing killer whales?

Plastic can end up in our stomachs too

Much of the fish consumed in Europe comes from fisheries in the Arctic Ocean, so we only have ourselves to blame if we end up eating the plastic waste that we helped to create and is consumed by fish in the area, says Duarte.

“We, humans, are to blame, as plastic is not a naturally existing material, but began to be mass-produced from oil in the 50s to support the “disposable life style” that has done so much harm to the environment,” he says.

Apart from supporting projects to clean up this plastic waste and supporting research into alternative materials that could replace plastics and do less harm to the environment, there is still a lot that individuals can do to reduce the amount of plastic waste entering the oceans, says Duarte.

For example, we can reduce our own use of plastic, especially single-use disposable plastic bags and water bottles.

Nielsen agrees. Better recycling schemes the world over could make a big difference, he says.

“We could start by replacing plastic bags with paper bags,” he says.

----------------

Read more in the Danish article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

External links

- Carlos Duartes profil (King Abdullah University of Science and Technology)

- Laura de Steurs profil (Norwegian Polar Institute)

- Torkel Gissel Nielsens profil (DTU)