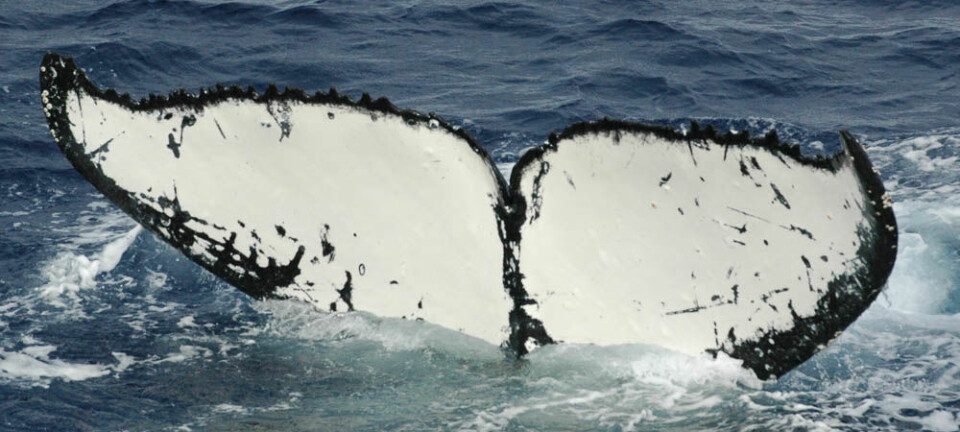

Why are banned chemicals still killing killer whales?

Levels of toxic PCBs in some whale and dolphin species are now so high that it could mark the end for one of Europe’s top predators.

A new study shows that three out of four whale and dolphin species in Europe have extremely high levels of the toxic compound PCB in their blubber.

PCBs are a group of toxic compounds that were used in coolants, paint, and building materials. They were banned across Europe in 1987, as their serious side effects to human health became clear--including links to cancer, and to their ability to attack our immune system and reduce fertility.

Now, a long running European study shows that our past has come back to haunt us as PCB has accumulated in many whale and dolphin species.

"PCBs have a variety of toxic effects and are ingested by animals at the top of the food chain. We see populations of killer whales, which have been studied for 10 to 12 years, that haven’t had a single calf—which means they’re at the risk of becoming extinct," says lead author Paul Jepson, from University of Oxford and head of the Conservation Governance Laboratory research group.

The new study makes for grim reading, according to Professor Rune Dietz, who also studies marine mammals at Aarhus University, Denmark.

"It's scary that substances that were banned 30 to 40 years ago, are still [found] in such high concentrations. The study is well done, and I think it’s a very fine contribution to an really important issue," says Dietz.

Pollutants passed from mother to child through milk

There are several reasons that PCBs are still found in the ocean. First, they accumulate in animals over time. As killer whales can live for as much as a 100 years there is plenty of time to accumulate high levels of PCBs.

Second, PCBs dissolve in fat, which means that they can be passed on to infants via their mother’s milk. A female killer whale can pass on up to 90 per cent of her PCBs to her calf.

This means that females should have fewer PCBs in their blubber than males. But this is not the case, says Dietz.

"Their [new study] figures show that the females can have higher PCB concentrations than males,” says Dietz.

The fact that females often have as high or higher levels of PCBs indicates that they are no longer passing on their PCBs to their calves. This confirms the scientists’ observations that many of these top predators are no longer breeding successfully.

“When the females have higher levels than the males it indicates that they’re not reproducing anymore. That means it [the pollution] has reached a point where it’s harming the animals’ reproduction. That’s scary," says Dietz.

Consumers need not be worried

The study is focused on whales and dolphins, but consumers should not be worried about similar threats to human health, says Professor Jens Peter Bonde from Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen University, Denmark.

"It's nothing, a Danish consumer should worry about, because we’ve known about this [PCBs] for many years,” says Bonde.

“We’ve been especially aware of this issue in the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Iceland for a while, because PCBs accumulate in marine mammals such as whales, dolphins, and seals, which are often consumed," says Bonde.

Bonde explains that scientists do not yet know the full effects of PCBs, but that it is a topic of intense research interest.

"There are indications of [associated] risks for a variety of diseases, ranging from cancer, to fertility, and the immune system. Many also believe that it can affect our metabolism and lead to obesity and abortions,” says Bonde.

“But these are things we fear and it’s still uncertain as to how big the problem is at the concentrations that people are typically exposed to," he says.

----------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex