One of Greenland’s first inhabitants had a hole in their sock

Greenland’s earliest people developed advanced technology that allowed them to survive on the sea ice. A single dress object from that time, a little seal skin sock, reveals unrivalled sewing techniques.

Have you ever had a pair of really good socks that you repaired again and again as you just could not bare to throw them away?

Archaeologists have uncovered such a sock that belonged to one of Greenland’s earliest inhabitants.

The seal skinsock was discovered in a settlement belonging to the Saqqaq Culture, which looks to have been repaired many times to fix a hole, just where a big toe would have poked out.

“It’s perhaps not so pretty after sitting in the ground for 4,000 years. But it’s the only dress object that we’ve found that we can say with certainty came from Saqqaq, and the sewing reveals an unrivalled technique,” says archaeologist Bjarne Grønnow from the Danish National Museum.

The first to master hunting on sea ice

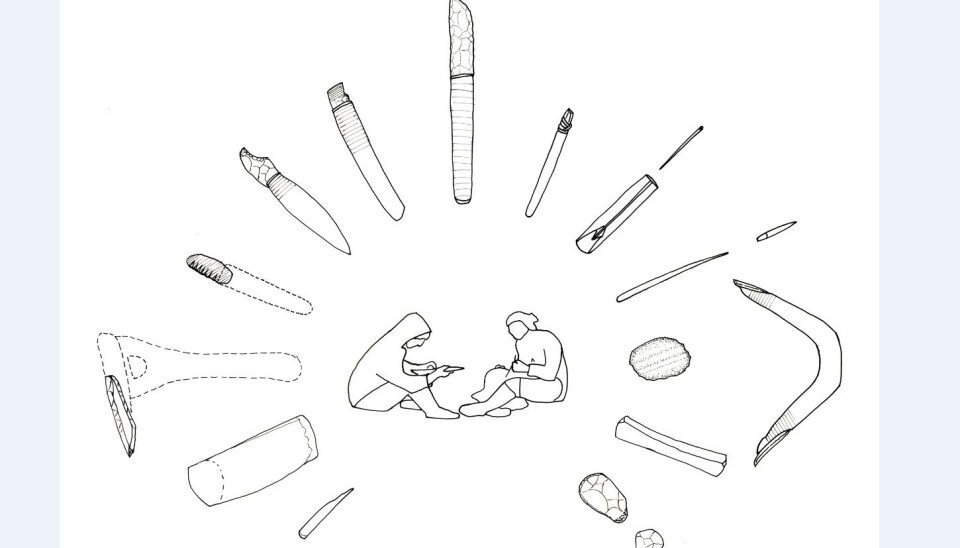

Archaeologists think that Greenland’s earliest people were master tailors. The fine stitching on the sock reveals advanced sewing techniques, with tight stitching using threads spun from thick animal tendons.

“It’s difficult to spin animal tendons and to do it so fine as they have here. We’ve found sewing needles made from bird bone and the eye of the needles are less than one millimetre. The Saqqaq peoples’ clothes must have been very beautiful,” says Grønnow.

The Saqqaq people were among the first to arrive in Greenland from Canada, around 4,500 years ago. While the so-called Independence I culture migrated north, the Saqqaq moved south and settled many areas, including Disko Bay in West Greenland.

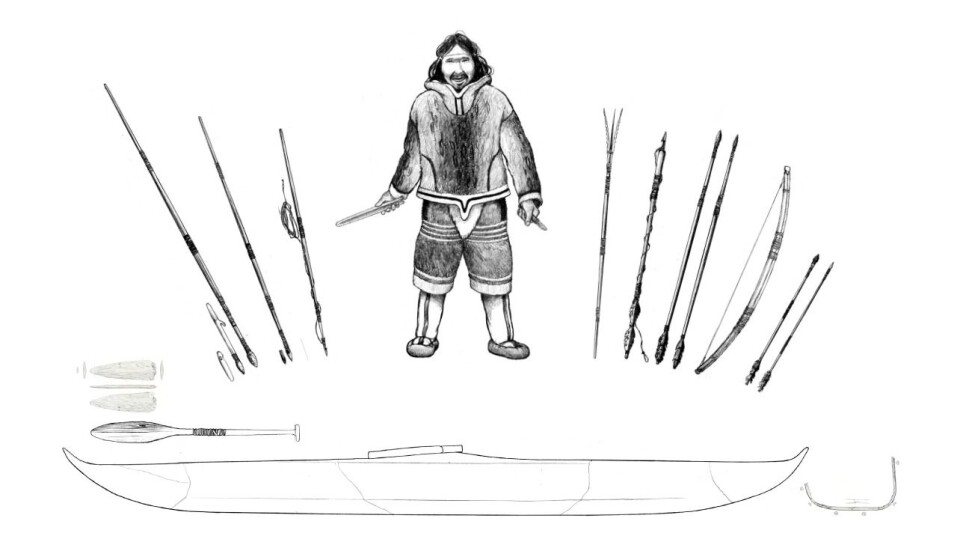

They developed technology, such as sewing techniques, advanced enough to master hunting on sea ice, making them the first to do so.

Read More: Arctic tomb preserves oldest known Inuit dress

Two frozen settlements and one sock

Grønnow has written up his findings as part of his doctoral thesis, studying the frozen permafrost layers from two Saqqaq settlements in West Greenland: Qeqertasussuk and Qajaa.

The Qeqertasussuk settlement was first discovered in 1983, and shortly after Grønnow’s mentor, Jørgen Meldgaard discovered the Qajaa settlement. Archaeologists at the time believed that the two locations were just the first of many, but this turned out not to be the case.

Qeqertasussuk and Qajaa are the only well-preserved settlements from the Saqqaq culture and the sock is the only dress item that has survived.

Read More: Inuit hunted whales 4,000 years ago

An “extraordinary” find

Archaeologists do not know exactly why so few leather objects survive in the Arctic from this period, says Anne Lisbeth Schmidt, a specialist in the preservation of Arctic dress at the Danish National Museum who has analysed the sock.

“I don’t actually know. But it’s certain that there’s a big jump in time where we don’t find dress objects. This is what makes the discovery so extraordinary: we simply don’t have any earlier objects,” says Schmidt.

She explains that the sock is sewn with a so-called overcast stitch, which is a simple but economical technique that does not leave an edge and therefore does not waste any material, or allow the edges to wear.

“It’s the simplest technique, but it’s sewn extremely finely, just as we see on many of the costumes from the Iron Age. There can be up to 50 stitches per centimetre. I’m very impressed by how tight it is. It’s hard to understand how they were able to sew so closely together,” says Schmidt.

Read More: Meet the Greenlandic spirits that gained power by sucking genitals

New knowledge on Saqqaq culture

Clothes in those days would not have lasted very long, says Schmidt. Early Arctic people may have replaced their clothes every year, and they may have had to replace their footwear multiple times during the year.

“Shoes wear a lot, because you always have to wear something on your feet. Otherwise, you cannot survive. You can imagine that this was more exposed to rock and hard surfaces than other items of clothing,” she says.

Still, it is rare for an archaeologist to see such attempts to repair a garment form this time, she says.

“We don’t see many repairs of old objects, but Bjarne may well be right that they did try to patch up the stocking. Perhaps it’s a reflection of the fact that they were forced to use what they had at hand, and to recycle materials,” she says.

Read More: New Greenlandic cuisine is changing cultural identity

Saqqaq people were style-conscious

One aspect of the study that strikes Grønnow is the lack of development in both design and technology throughout the 2,000 years recorded at the two settlements in Disko Bay.

The Saqqaq people taught themselves to hunt on the sea ice and populated an area bigger than Europe, but then little seemed to change over the next 2,000 years.

“From the two settlements we can follow them from when they arrived in Greenland, right up to the time when they inexplicably disappear. Throughout almost all of that time, their design and technology doesn’t change. Most cultures change fashion and style over time, but the Saqqaq people stick to their design all the way through,” says Grønnow.

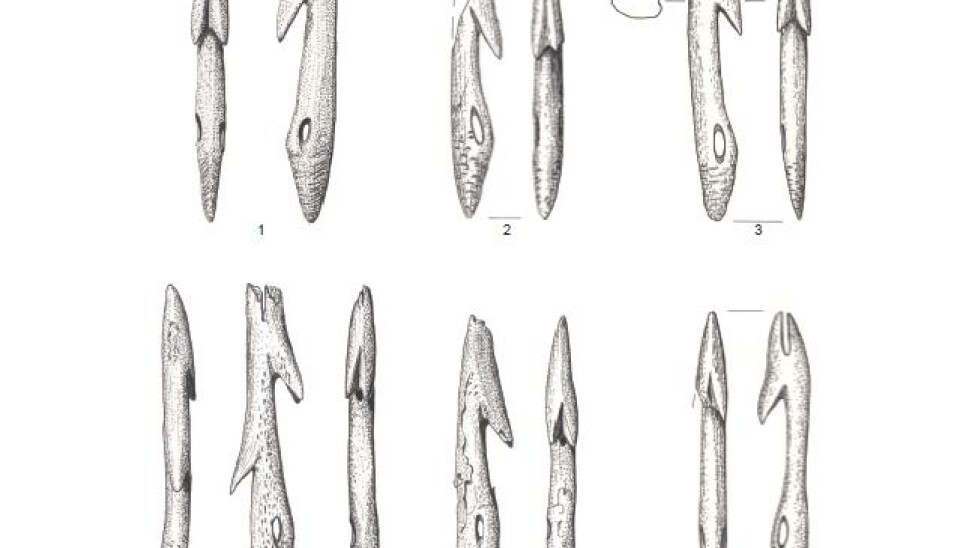

“When I started this work, I thought that I really had to sort out the chronology of their development. But it just couldn’t be done. The arrowhead design is the same. The lance tips are the same. The harpoons are the same. It could have been done differently a billion times and with all sorts of stylistic features, but it’s just all the same. I’ve never experienced anything like it.”

Read More: World’s oldest vertebrate discovered in Greenland

Rapid population expansion created a need for identity

One example of this consistency is in their choice of raw material to create stone tools. Saqqaq people used a rock called killiaq—a type of slate with flint-like properties. Killiaq is only found in Disko Bay, where the Saqqaq first settled.

No matter how far the Saqqaq moved and wherever they settled, they used killiaq stone for their tools.

“Early on they discovered this particular type of slate, and they then based their entire stone technology on it. Even if they lived 500 kilometres away, they used this stone. Apparently you weren’t a real Saqqaq person if you didn’t use tools made of this rock,” says Grønnow.

He suggests that this consistency served as a fixed point of reference for a people who had become so widespread, so quickly.

“How do you hold firm in your identity when your culture is constantly spreading and people are moving to new areas? Probably by creating identity markers, so even if you are separated in time and space, you can still identify that you are part of this community,” says Grønnow.

---------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article

Translated by: Catherine Jex