Meet the spin doctors of the fifteenth century

Medieval political spin doctors and lobbyists may have used different methods to their modern day counterparts, but their goals were very much the same.

This article is part of our Basic Research theme

Lobbyists and spin doctors are by no means a modern phenomenon.

They were already active players in medieval politics, seeking influence on those in power. Some of their methods were similar to what their modern counterparts still use, others were somewhat different to what we recognise in today’s political landscape.

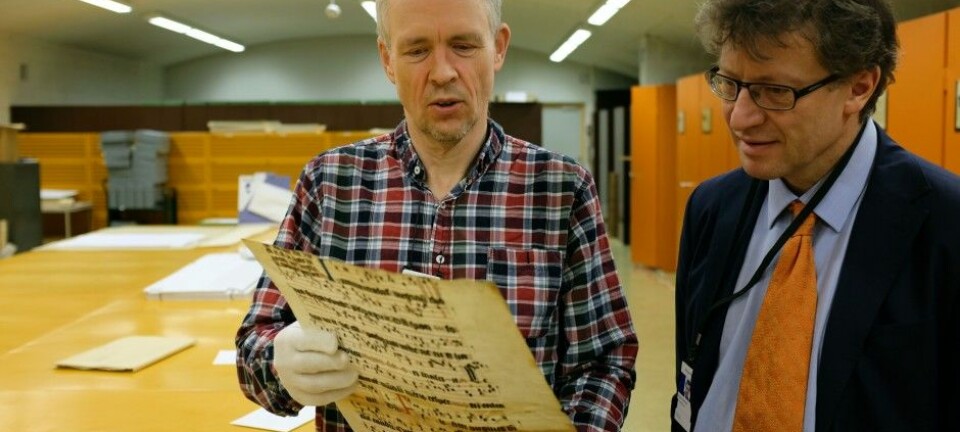

Kristin Bourassa, a postdoc at the Centre for Medieval Literature at the University of Southern Denmark, studies medieval political lobbyists and how politics in old European monarchies were discussed and influenced.

“I’m interested in how authors of the medieval texts chose to target their messages. And it can be very similar to the ways in which lobbyists and spin doctors do it today,” says Bourassa.

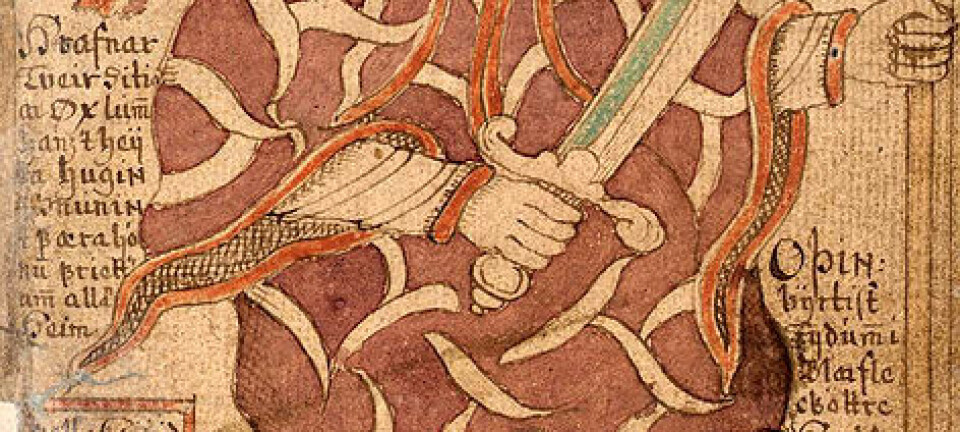

Read More: Medieval texts colour our knowledge about Odin

Works of fiction helped advise Kings

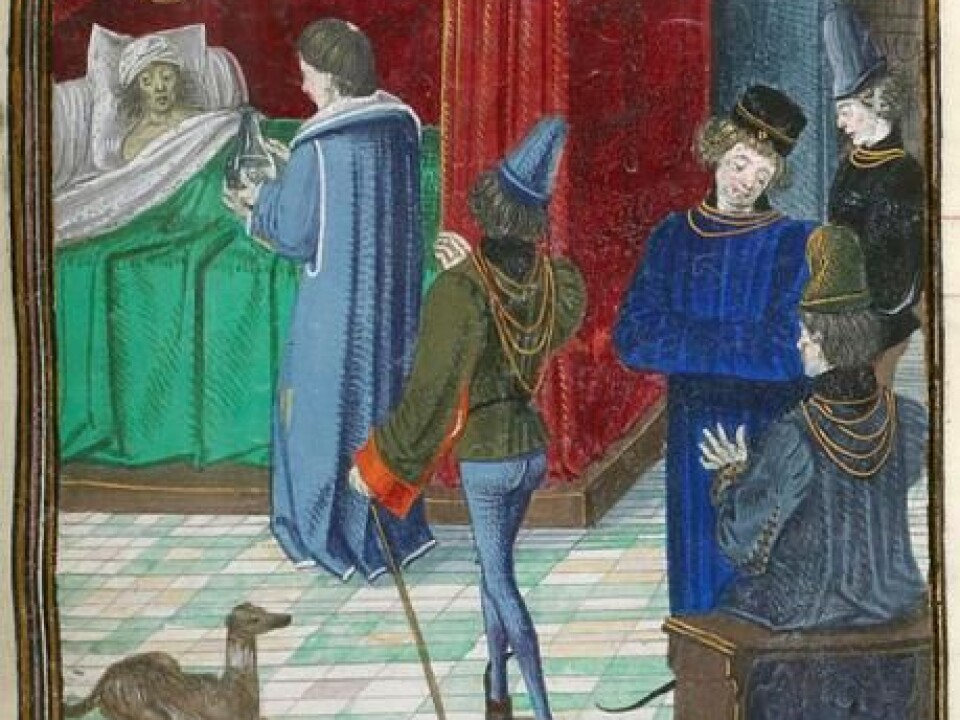

One of the texts she is working on was written by the French advisor Pierre Salmon who at the start of the 15th Century wrote the book “Dialogues”. It was intended to catch the attention of royal advisers to King Charles VI of France and perhaps even his young son, Crown Prince Louis.

“The text is a dialogue between a fictional version of the King and the author, in which Pierre Salmon tries to directly and indirectly explain to the king what he should do,” says Bourassa.

In the book, the fictional king asks the author for advice.

“We have not had proper knowledge of ourselves, nor of the very great grace and glory that God has given us…We ask that you tell us, in your opinion,what habits and conditions the king must have,” says the fictional king.

Read More: Norwegian viking saga confirmed by archaeological discovery

Listen to good advice

One of these habits should be to listen to good advice.

“I know very well that in your kingdom and your household and your person there will come such great damage that if God in his mercy does not take pity on you, you will lose the crown of your kingdom, and the name, glory, and power of kingship, if you do not remedy your person and your governance by believing in and following good advice,” says Salmons in response.

The book is available in two versions: one from 1409 and another from 1415. And there are distinct differences between the two.

“It’s edited because so much had happened in the intervening years. His mission in the first edition is to shape the King, but in the second edition I’m now working from the interpretation that he was now targeting the son Louis as the situation had changed dramatically in France during those six years,” says Bourassa.

Bourassa has transcribed both of the texts, which indirectly criticise the King’s reign.

“It may be surprising that in this time, one could write to the king to say that he was actually doing a really bad job of it. But you could, if you used the right format,” she says.

Read More: Guide to the classics: the Icelandic saga

King Charles may have been schizophrenic

At the beginning of the 15th Century, Europe had two popes: one in Rome and another in Avignon in present day France.

“At this time, different kings support different popes. Pierre Salmon thinks that there should be only one pope, and his goal is to replace the two rivals with a third pope,” says Bourassa.

One of the challenges in French political life at this time was that Charles VI was mentally ill. It is possible that he suffered from what we today call schizophrenia.

“He tries to find a man who can cure the King, who the whole court is worried about. He also tries to get the King’s noble advisers to help,”she says.

Read More: What this coin can tell us about ancient politics

The book was never finished

Salmon urges the court to stand together on the issue of the sick Charles VI and to stop their own infighting.

“He tries to get the different nobles to work together. There’s a big gap between the two camps fighting for the King's favour, and they have many conflicts, sometimes armed conflict,” she says.

But his warnings were in vain, and civil war broke out in France.

“This is why the second edition was so different. There was a new situation and new ears to reach,” says Bourassa.

“It seems that he now targeted the messages at the Crown Prince. The 1415 edition is more general and he calls for the civil war to end,” she says.

But Salmon’s advice is once again in vain as Louis dies at the age of 17, in December 1415.

“Pierre Salmon stops working on the book once Louis dies. The text and some illustrations are ready, but the last images were finished much later, which is shown by a talented art historian. So it’s reasonable to believe that Louis was the target for this edition,” says Bourassa.

Read More: New discovery rewrites history of Denmark’s biggest royal castle

“The youth wear foolish clothes”

Contemporary spin doctors and lobbyists no longer use fictionalised works of literature to wield influence, but the goals have remained essentially the same: to attain power and influence.

Even though the text that Bourassa is studying is now 600 years old, the thoughts of these political players are more or less the same as today.

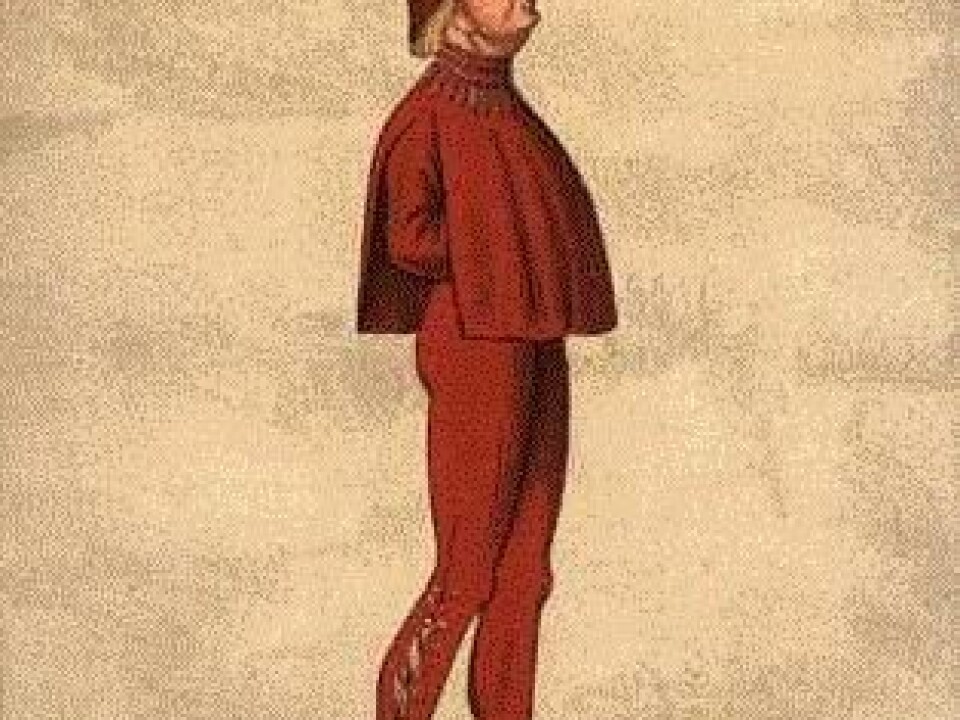

One of the messages in another piece of fiction written to influence Charles VI was Phillippe de Mézières’s “Dream of the Old Pilgrim” in which one character, Queen Truth, says:

“Men wear clothes that show the shape of their bottoms and of their vile members.”

She is saying that young people dress foolishly, says Bourassa.

“I think that we can see that she’s using a euphemism. She thinks that people’s clothes are too tight and there’s not enough of them,” she says.

Read More: ’Twas dangerous to insult a Viking

People are much the same now as they were in medieval times

But why should we care about medieval political wheeling and dealing today?

“I think that there’s value in realising that what we believe to be new and original today, was actually around hundreds of years ago. There’s a tendency to see the past through either rose tinted or black spectacles. Some think that the middle ages were either bad or good,” says Bourassa.

“But the world was also nuanced back then,” she says. “Just as we do today, they also had to work with ineffective governments and had great dilemmas and political challenges. And they thought carefully about it. So I get irritated when people talk about the ‘dark ages’. There were plenty of sophisticated thinkers.”

Pierre Salmon does appear to have one distinguishing feature from many of today’s spin doctors: he openly admits his shortcomings, says Bourassa.

“He recognises that many of his attempts to influence policy didn’t work. The later version of the book contains a letter to the king, in which he admits that not all of his advice was effective, and asks to be allowed to leave the court,” she says.

----------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex