Medieval texts colour our knowledge about Odin

Researchers disagree on the Viking Age conceptions of the god Odin. The source material is ambiguous and difficult to interpret.

Today, the general conception of Odin is that of the one-eyed chief of the Norse gods. However, when it comes to the general conception that was prevalent in the Viking age, researchers disagree.

As there are no contemporary source texts to the pre-Christian religion, researchers need to use medieval sources. This has given rise to a multitude of interpretations.

The stories and texts that have been handed down from the Middle Ages are marked by the Christian way of thought that was characteristic of the time.

Because of this, it is exceptionally challenging for the researchers to estimate whether the information regarding the god can in fact be traced back to the Viking Age.

Up until now, research history shows us that the method for understanding Odin has been wrong.

The different academic backgrounds of the researchers have also influenced the interpretations of the original Odin, as have the various research trends and methodologies that have come into play.

“Up until now, research history shows us that the method for understanding Odin has been wrong,” says Annette Lassen.

She holds a PhD in Norse Philology from the Department of Scandinavian Research at the University of Copenhagen and has recently published a book (available in Danish only) on the diverse representations of Odin found in medieval texts.

In her analysis, she has reached the conclusion that researchers should weed out the Christian perception of Odin in order to arrive at the original conceptions of the god.

Basing a thesis about the pre-Christian Odin on a series of elements from medieval texts about Odin presupposes an interest in whether those elements come from Christian ideas.

“Regarding medieval texts as a single, heathen text and extrapolating an image of Odin from this is not a viable option. The texts are very diverse,” she says.

Christian traditions have coloured the image of Odin

The medieval texts paint a picture of Odin. In the Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson’s (ca. 1178-1241) handbook for skalds, the Nordic chief deity is portrayed as a skaldic god.

Other texts present him as a war god, while others still depict him as a devilish figure.

Some sources know him as an immortal Father of the Universe, resembling the Christian God, while others see him swallowed by the wolf in Ragnarok, or dying from old age as an immigrant nobleman in Sweden.

The texts vary, partly because they are drawing upon Christian traditions, and partly because the writers have different intentions with their texts.

“The description of Odin is tied in with the Christian model of interpretation employed by the writer,” she says.

According to Lassen, there are a number of different Christian models of interpretation for dealing with heathenism, dating back to the early Church:

- The writer presents heathen gods as heroic figures who have been mistaken for gods by the heathens.

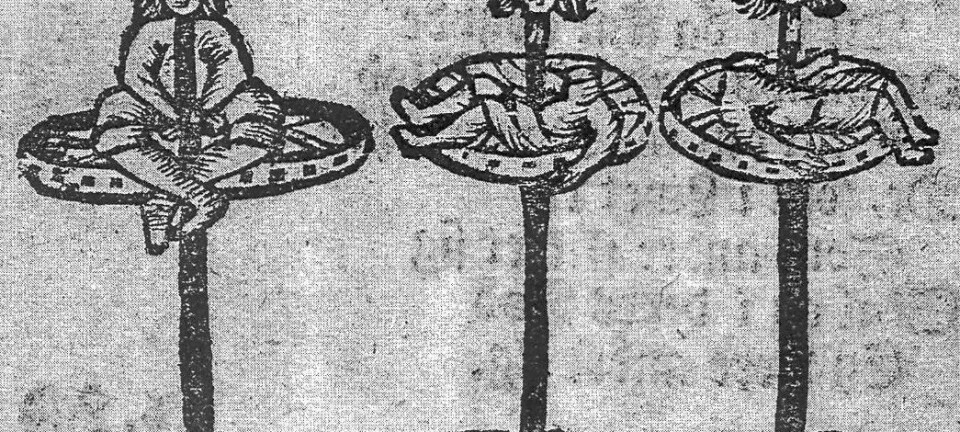

- The gods are described as demons. Demons could inhabit statues of the heathen gods, which were worshipped by the heathens.

- Heathen worship is described as a misinterpretation of Christianity. In the Biblical story about the tower of Babel, God prevents the builders from speaking to one another by dividing the original language into several different ones. According to the medieval version, the original and ‘true’ language (Hebrew) was forgotten and with it also the original and true God. In this way, the misinterpreted versions of the ‘true’ faith were spread.

A call for circumspection

According to Lassen, once the Christian way of thought has been identified, not much information is left about Odin in the old sources.

She says that while archaeologists and historians of religion may not necessarily agree with this, there is not likely to be anyone disagreeing that it is necessary to analyse the Christian additions, before starting to look into the original Viking Age conception of Odin.

“My aim with the book was to focus on the Medieval Odin figure, clarify the extent to which Christianity has shaped our ideas of heathenism and demonstrate that this calls for circumspection, but also to come up with a method that other researchers can use,” she says.

“Basing a thesis about the pre-Christian Odin on a series of elements from medieval texts about Odin presupposes an interest in whether those elements come from Christian ideas.

“That doesn’t mean that the myths about Odin are lost. The stories exist, and they are as entertaining and interesting as ever. It just turns out that they are a fascinating product of the meeting between heathenism and Christianity,” she says.

“Mythology is probably always like that. Something can always be added to it, and it never exists in any pure form.”

Translated by: Iben Gøtzsche Thiele