EU authorities too slow: People exposed to endocrine disrupters for decades

It takes decades to ban substances suspected of containing endocrine disrupters. The process is far too slow and could have consequences for our health.

When you go shopping, you run the risk of purchasing something that contains harmful endocrine disrupters.

Even though the European authorities suspect a product contains endocrine disruptors, it may take decades before it is officially classified as such and removed from store shelves.

For example, it took almost 30 years for the plasticizer DEHP, which is found in children’s toys and other plastic products, to be categorised as an endocrine disrupter. It was first suspected in the 1980’s, but it was only banned in 2017.

It is not unusual that an evaluation “takes many years,” says Finn Pedersen from the Danish Environment Protection Agency, which oversees regulations on the chemical industry for products such as paint and plastics.

Read More: Bad chemistry: Chemical companies fail to comply with EU regulations

The long evaluation times can have big consequences for our health, say scientists.

“Sales of these substances continue as long as they are under evaluation by the EU. This means that consumers are exposed to potentially harmful materials throughout, which in the long run can have consequences for their fertility and health,” says Ulla Hass, professor in the Research Group for Molecular and Reproductive Toxicology at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

“The [EU] process is generally very slow,” she says.

See how the process works in the interactive graphic below.

Explore the interactive graphic to see how the EU evaluates hazardous substances

Dangerous for consumer health

Endocrine disrupters are dangerous over long exposures, both in high and low doses—and in combination with other substances, which creates a “cocktail effect,” says Anna-Maria Andersson, research leader at the Center for Endocrine Disrupters (CeHoS) and research scientist at the Department of Growth and Reproduction at Rigs Hospital, Denmark.

Pregnant women should be especially aware of endocrine disrupters in cosmetics and foods as the foetus is exposed to harmful substances via the placenta, says Andersson.

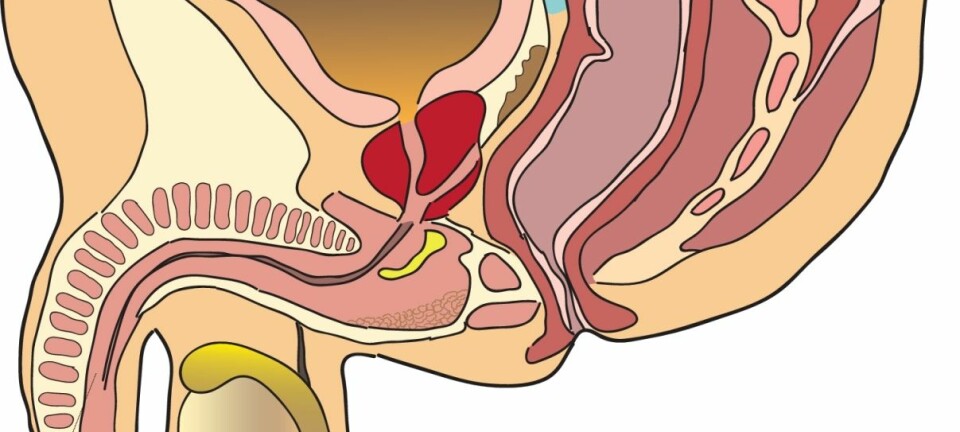

“Precursors to testicular cancer can occur during pregnancy if the hormone balance is disturbed by hazardous substances,” she says.

Endocrine disrupters are also linked to breast cancer, low sperm count, and genital birth defects.

What are Endocrine disrupting chemicals and why are they so harmful? (Video: Kristian Højgaard Nielsen / ScienceNordic)

THINK Chemicals, an initiative under The Danish Consumer Council, describes the prolonged process from initial suspicion to final evaluation as unacceptable.

“It’s unacceptable that it takes such a long time. Consumers are not adequately protected during this long period and it’s our opinion that it should take a shorter time from when harmful effects are observed in animal trials and to the substance being banned from use by people,” says Stine Müller, project manager at Think Chemicals.

“The best situation would clearly be if consumers could be sure that their products didn’t contain any endocrine disrupters. Unfortunately, this isn’t possible and therefore the next best thing is that we are properly informed about potential harm. This is not the case today,” says Müller, who calls for more transparent information from the EU of substances that are currently under investigation.

Read More: Endocrine disrupters in food and clothing replaced by equally dangerous chemicals

EU disagree on a solution

MEP Katarina Konecna from the Czech Replublic who serves on the European Parliament Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety agrees that the processes takes far too long.

“The EU process is too slow. At the same time, the [European] Commission is constantly granting special approvals of suspected substances instead of respecting the precautionary principle that will protect our health as European citizens,” she says. “We totally ignore the academic studies that highlight harmful substances”

EU spokesman for health and food safety, Enrico Brivio, takes a different view.

“It’s very complex to show that a substance is an endocrine disrupter, and therefore it’s a long process. We do everything that we can,” he says.

Brivio points out the EU citizens are far better protected from endocrine disrupting substances than people in the US and elsewhere in the world.

Read More: Chemical cocktails in foods increase cancer risk

Difficult to show an effect on the hormone system

Another speed-bump in the process is the fact that it is difficult to demonstrate that a substance disrupts the human hormone system.

Tests are usually conducted on rats or in culture, but never directly on humans due to ethical reasons. And this presents a challenge, says Hass.

“Animals and humans are naturally different. People are more sensitive to these substances than animals. We take this into account and try to identify the dose that people can tolerate, but it can still be difficult because there’s a great deal of uncertainty around how endocrine disrupters affect us,” she says.

Even if a particular substance is shown to be an endocrine disrupter in rats, it does not immediately follow that it has the same effect in humans, says Pedersen.

Read More: Sperm harmed by soaps and suntan lotions

“If we are to ban something and remove it from the store shelves, then we need to be able to document a real risk to humans and we’re not sure we can, even when we know that it is an endocrine disrupting substance in animals,” he says. “The best thing is to mark the substance as suspect.”

A list of suspected substances can be found on the European Chemicals Agency’s (ECHA) website, though the information and documentation vary in quality, says Hass.

The EU needs to find a way of notifying consumers that a substance is under investigation, she says.

“A good option would be a mark on the back of products for suspected substances. But then of course manufacturers will feel that their products are blacklisted without adequate evidence,” she says.

It may fall to others to draw awareness to the products, suggests Hass.

“As scientists it’s our task to evaluate the health aspects of endocrine disrupter substances. And we also come up against the problem of long evaluation times and long term consumer health,” she says.

---------------

Read the full story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

External links

- Ulla Hass

- Anna Maria Andersson

- Finn Pedersen

- Magnus Løfstedt

- Stine Müller

- Katerina Konecna

- Enrico Brivio

- Candidate List of substances of very high concern for Authorisation (ECHA)

- List of Undesirable Substances (LOUS) (Danish Environmental Protection Agency, in English)