Climate scientists build laboratory under the ice with a balloon

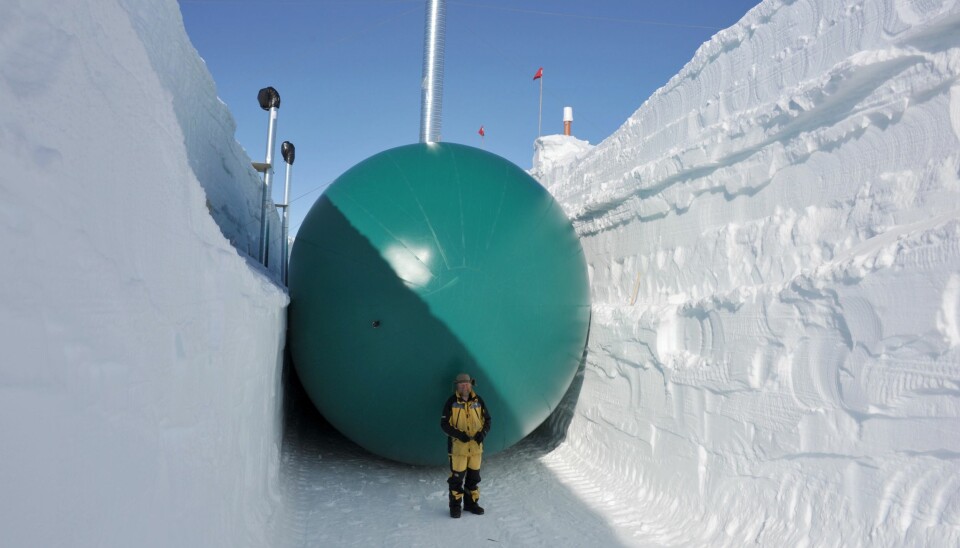

Climate scientists working in Greenland can now construct field laboratories using a giant balloon. The result is a hall under the ice suitable for scientists and visiting tourists.

Scientists now have an unexpected new method to build laboratories under the ice in Greenland and Antarctica—using a balloon.

The new method places a large balloon into an excavated pit and covers it with snow. After a few days the snow is hard enough to function as a roof. The balloon is then deflated and removed, leaving a smooth and solid hall, hidden under the surface of the ice sheet.

The submerged field laboratory can then be used by climate scientists and glaciologists while they study the Greenland ice sheet.

“We’ve been up and installed the equipment. It all appears to be working well and the halls are very stable. We’re excited to see what it will be like to work there,” says Steffen Bo Hansen, an engineering assistant at the Centre for Ice and Climate at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Hansen has worked with ice cores since the 1970s. The team are now back in Greenland to install more equipment and collect ice samples.

Read more: Nordic project will solve a riddle of dramatic climate change

Ice records Earth’s past climate

Inside the hall, scientists and engineers are setting up drilling rigs to drill down into the ice and collect ice cores to investigate how climate has changed in the past.

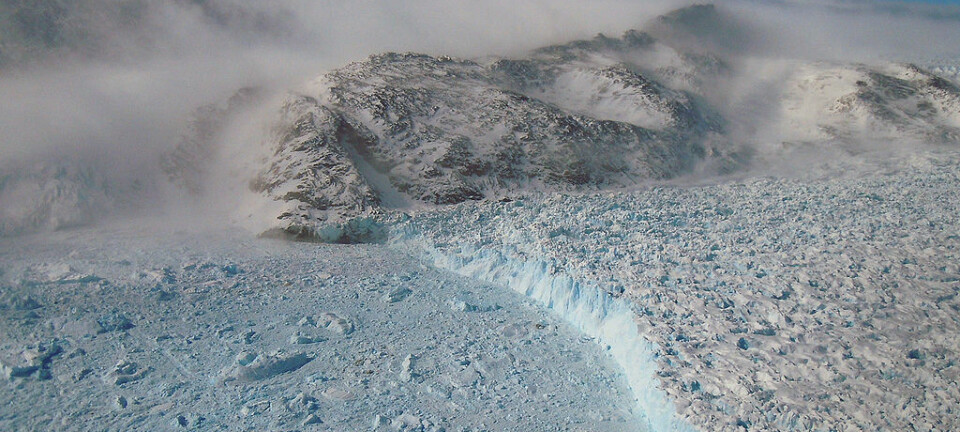

The old ice can reveal what the Earth’s climate was like in the past and gives us a better understanding of what might be awaiting us as our climate warms due to man-made climate change.

The oldest ice in Greenland dates back to approximately 130,000 years ago and records information of, for example, the Earth’s temperature and atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases between then and now.

After drilling an ice core and preparing it in the field laboratory under the ice, it is shipped back to laboratories like this one at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark. See what the scientists do next and how they use the core to see what the Earth was like in the past. (Video: Kristian H Nielsen / ScienceNordic)

Old method was a waste of wood

Drilling ice cores is a tough job in one of the harshest environments on Earth, where temperatures reach well below freezing.

Typically, it’s done inside a trench to protect the scientists and their work from the harsh Arctic winds and weather.

Until now, the large excavated field laboratories had timber ceilings of beams and plywood. But this was less than ideal.

Not only was it an expensive way to construct the laboratories under the ice, it was also cumbersome to transport the heavy wood to Greenland and up onto the ice sheet. There are also the physical limits of the wood itself, which after just a few years begin to buckle under the weight of the snow that builds up on top.

Laboratories built using the new balloon method should last longer and the technique is a more environmentally friendly system, which can save the scientists a lot of time and hassle.

Read More: How the Greenland ice sheet fared in 2016

A Danish design

Professor Jørgen Peder Steffensen from the Center for Ice and Climate at the Niels Bohr Institute was the first to suggest the idea of using a balloon to construct their field laboratories.

“We have to leave enormous amount of timber in the snow, because the roof beams break under the pressure. It made me think whether there was a more environmentally friendly method to build the halls, using nature’s own materials,” says Steffensen.

“I knew that when the snow lands after passing through the snow blower, it becomes rock hard after a few hours—almost like concrete. In the snow-blower the snow is shredded so that the crystals are broken and packed tightly together,” he says.

The scientists built a 15 metre by 4.2 metre test balloon in 2012 to see whether the idea could work.

“It was a little smaller than the balloon we wanted to use. The inflated balloon lay in the excavated hall like a hot dog sausage in a bun and we blew the snow on top and built up the ceiling,” says Steffensen.

After three days they switched the pump off, let the balloon empty and pulled it out to reveal a solid snow hall.

In the following years, the scientists checked to see how the new hall was holding up. And in 2015, they decided it had been a success and were ready to try it out for real.

Read More: Greenland Ice Sheet has already caused nearly five metres sea-level rise

Deployed to the EastGRIP coring site

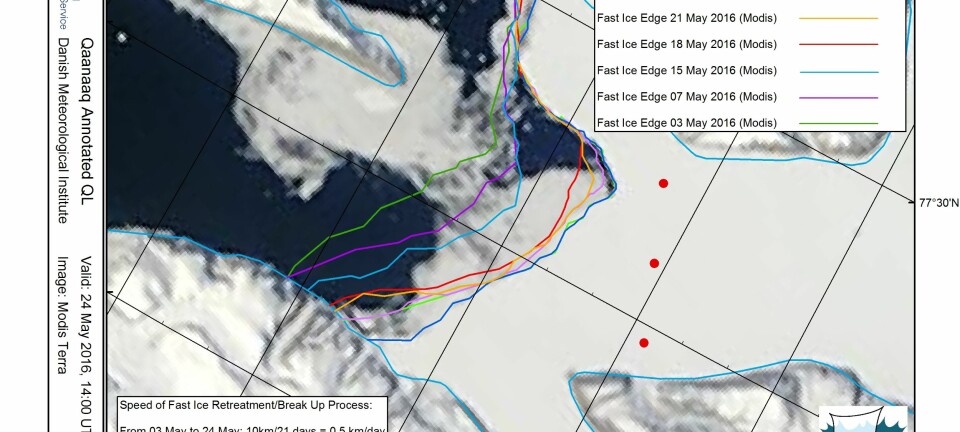

The method has since been rolled out to the EastGRIP coring site in Northeast Greenland last spring. Here, scientists will drill down to the bottom of the Greenland ice sheet, 2.5 kilometres into the ice.

This time they used a 35 metre long, five metre wide balloon to build the laboratory that will house the drill site—about the size of three city buses.

They built a large structure consisting of three halls, two shafts (an elevator shaft and a staircase), an ice core storage facility, and a 40 metre long ramp down into the site. The bottom of the hall is seven metres beneath the surface. In all, it took ten large balloons to build, which can be used again and again.

Read More: Caves will reveal Greenland climate from before the ice sheet

Ice hotels can be built quickly and cheaply

The new method has sparked international attention from scientists from the USA and France for use in their own projects. And Steffensen expects the UK and Germany to also use the technique.

But it is not only of interest to other scientists.

“I’ve also suggested that the Greenland Parliament could use the method. You can build visitor centres in the ice sheet for relatively little money. And tourists can pay to stay overnight in the snow hall. It’s far too expensive to construct buildings on the ice sheet, but snow holes can be built relatively cheaply with balloons,” says Steffensen.

---------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex