Study ranks Nordic health care among best in the world, except Denmark and Greenland

Denmark and Greenland rank bottom in the Nordics when it comes to the treatment of diabetes and other deadly diseases, shows new study

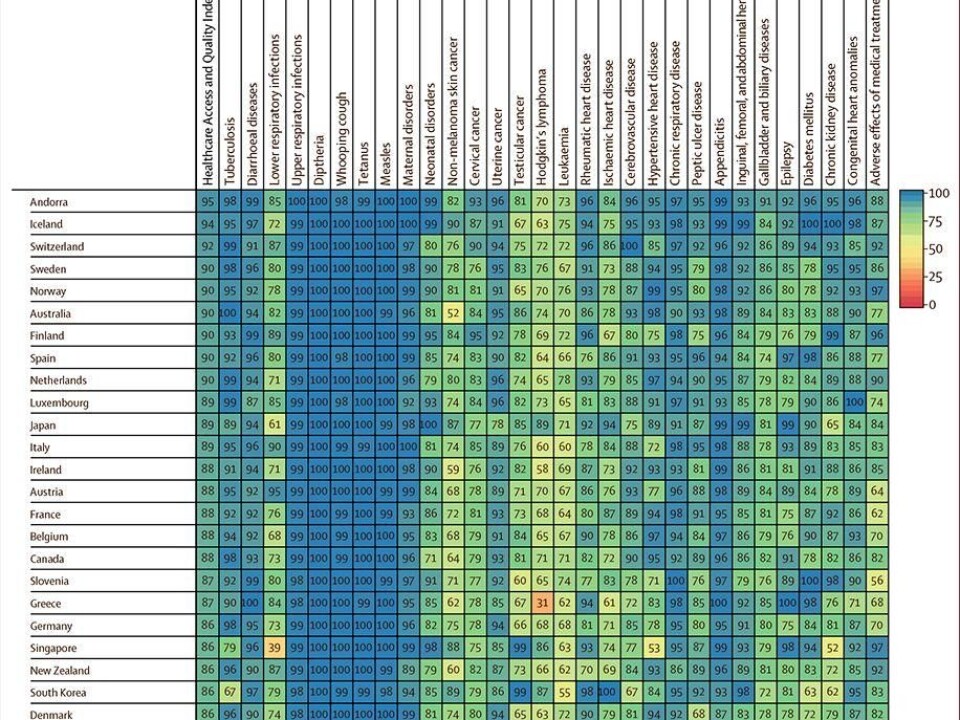

If you are struck down with a deadly disease then you had best hope to be treated in Andorra, and not Central African Republic, who are ranked as having the best and worst health care system in the world, respectively, according to a large study published in The Lancet.

You would also be in good hands in the Nordic countries. Iceland, Sweden, Norway, and Finland all rank at the top of the list in their ability to avoid patient death in 32 specific diseases.

In fact just two Nordic nations do not make it into the top ten—Denmark and Greenland, which are all the way down at 24 and 58 on the list of countries’ ability to treat for example diabetes, stomach ulcers, and various types of cancer. The Faeroe Islands were not part of the project.

“By measuring healthcare quality and access, we hope to provide countries across the development spectrum with valuable data on where improvements are most needed to have the biggest impact on the health of their nation,” says senior author Professor Christopher Murray from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, USA, in a press release that accompanied the article.

Strong study builds on data from thousands of researchers

The study is strong for a number of reasons, says Kim Moesgaard Iburg from Aarhus University, Denmark, who contributed to the study:

- It is the first study to compare health care systems in 195 countries across the world for a period of 25 years, and not just Western countries and OECD nations.

- The study builds upon The Global Burden of Disease Study—a worldwide collection of data with contributions from over 2,300 scientists.

- The scientists have standardised for influences by our environment and by our own unhealthy lifestyle habits such as smoking and drinking alcohol, and each country is scored on their ability to avoid unnecessary patient deaths in 32 specific diseases as an indicator for how well health care systems function compared to their socio-demographic level of development.

Almost all deaths caused by these 32 diseases should be partly or fully avoidable when a health care system is functioning optimally.

“The study also points out where health services can improve. If we look at Denmark, there’s for example something to be gained in diabetes and chronic kidney disease due to diabetes. For Greenland, especially neonatal disorders is a huge problem,” says Iburg.

Professor: Two weaknesses in the otherwise interesting study

A weaknesses of the new study is the limited number of diseases considered—just 32—and the fact data from each country are adjusted in order to compare from one place to another, says Rikke Søgaard, professor in health economics at Aarhus University, Denmark.

She points out two further weaknesses in the study.

First, despite the fact that the scientists have conducted a “large analytical effort and based their measurements on the recognised Global Burden of Disease Study,” it is still difficult to compare causes for these deaths as it is not entirely clear which countries conduct autopsies, she says.

It is also difficult to identify a single cause of death. For example a patient may live with cancer for many years and final succumb to an infection of the airways, says Søgaard. What is the real cause of death in this case?

Second, she questions whether the number of deaths from these 32 diseases is really an indicator of the quality of services. For example, services in Denmark are judged by core values of service, such as involving patients and carers, ensuring patient rights, and value for money. The new study does not take such factors into account.

“[Denmark’s] place at number 24 out of 195 health care systems must of course be seen in light of what we are being judged on. We don’t get any points for when we in Denmark prioritise funds for, to name some examples, prevention or treatment that don’t prolong life but improve our lives. This also applies to access to expensive medicines or faster assessments and treatment in our waiting policies,” says Søgaard.

A limitation of the study is that it omits other fully or partly treatable disorders, which do not necessarily kill people, such as depression, muscular skeletal disorders and cataracts, and it does not distinguish between treatments by practising doctors and hospitals, says Iburg.

Progress in 25 years, but still great inequality

In general, health care systems around the world have developed in a positive direction during the study period between 1995 and 2015.

The study scores countries as to how far away they are from meeting their full potential. Denmark has increased from nine points short of its full potential in 1995, to five points in 2015. Sweden have also moved closer to their target.

According to the researchers it is bad news that inequality has risen since 1995, with countries at the top even more separated from those at the bottom. But this is not necessarily negative, says Morten Grønbæk from the National Institute of Public Health at the University of Southern Denmark.

“When I look at the [trends] for Denmark, I can see that inequality rises as the rich are becoming healthier. But that’s not because the poor are becoming unhealthier, it’s just because they don’t follow the curve. It’s good for the rich and bad for the poor, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s going in the wrong direction,” says Grønbæk.

And inequality in healthcare is also something that rich western countries should be aware of, he says.

“The more educated cope better with the same diseases than the less well-educated. This is because they’re better able to ask the doctors, understand the messages, and take the right medicine in the right amount, and so on. Here we need to do something, but there’s also focus on this in the healthcare system,” says Grønbæk

---------------

Read more in the Danish article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex