Teachers don't know how to accommodate the smartest pupils

In every elementary school classroom, one to two pupils on average need faster and more challenging instruction than their classmates. Teachers interviewed in a new Norwegian study say these pupils are not prioritized in schools.

A lot of people would call it a luxury problem.

Having a son or daughter who is smarter than everyone else in the class may seem like a good problem to have. But a lot of these kids have a hard time.

Some feel useless and stupid. Some kids get bored and cause a lot of trouble. And many of them are excluded from social groups and become lonely.

Some even become truant and eventually drop out of school.

Unfamiliar with needs of high-ability pupils

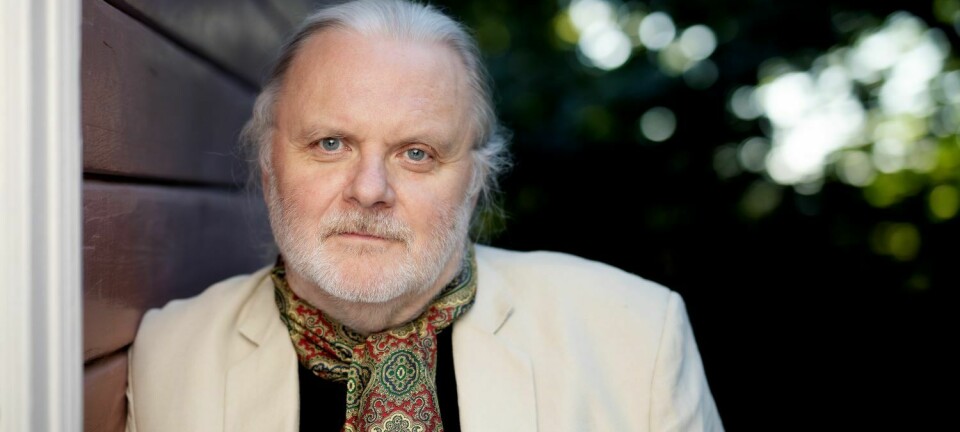

Astrid Lenvik is a PhD candidate at the University of Bergen and is pursuing a doctorate in special education. She is studying pupils who have “extraordinary learning potential”.

Her preliminary results confirm what has been shown by other researchers: It’s not always easy to have stronger abilities than your age-mates.

Lenvik also surveyed 339 teachers on the experiences they’ve had with this group of children.

In Lenvik's survey, 74 per cent of teachers said that they have had high-ability children who fit into the extraordinary learning potential category. Forty-four per cent of respondents believed they had such pupils in class at the time of the survey.

However, 14 per cent reported that they have no knowledge about this group of learners at all.

Lenvik finds this a surprisingly high percentage.

Learned about them on their own

Another finding is that the vast majority of teachers, almost nine out of ten, think they know too little about this group of learners and need to increase their understanding about how best to facilitate their learning.

Teachers who are already knowledgeable about gifted learners have largely educated themselves. Nearly half of the teachers say that they have become informed through their own experiences and by finding relevant literature on their own.

Only a few credit their teacher education programmes, which at best barely touched on the topic.

Lenvik found no particular characteristics that typified the teachers who believe they don’t know anything about this group of pupils. Their experience was varied and included long-time teachers and ones new to the field.

She says this makes her think that the topic of high-ability children hasn’t been part of the recent teacher training curriculum.

Schools don’t prioritize gifted learners

Almost all of the teachers in Lenvik's survey believe that these academically gifted learners need strategies and support beyond regular instruction. But many also think that the current school system doesn’t allow for this.

Close to 60 per cent of the study respondents believe that the school system does not prioritize creating true learning opportunities for this group.

A principle in Norwegian schools is that instruction must be adapted to each pupil’s abilities and aptitudes.

Pupils with high ability are entitled to differentiated education. They are not entitled to special education. But differentiated education is not an individual right like special education. Special education is intended to cover pupils who are falling behind and who need extra support, Lenvik says.

“When we look at the needs, I believe that this group of pupils should have the same right. High-ability kids need such a different type of instruction than the rest of the class, that it's difficult for the teacher to accommodate their needs in the regular teaching,” says Lenvik.

Aftenposten, Norway’s largest printed newspaper, recently wrote that seven out of ten school owners have no plans for accommodating pupils with great learning potential.

Can smart kids fend for themselves?

“One myth is that this group of learners can fend for themselves,” says the researcher. “This probably explains a lot of the reason for this assessment.”

Lenvik believes that it should be possible to accommodate these pupils in regular schools, but systemic challenges are hindering it.

For example, some pupils want to take higher-level subjects, such as lower secondary math while they are still in primary school. But the extent to which schools offer this option varies considerably. She believes this variation is problematic.

Let them go deeper

Lenvik thinks the best way to meet the needs of high-ability students is either to allow them to progress faster in the subject matter or to make better use of the breadth of subjects.

She advises teachers to familiarize themselves with Bloom's taxonomy. This model incorporates different levels of learning. Students can work on the same theme, but at different depths.

“Teachers can let high-ability students work on topics within the same main theme as the rest of the class, but let them go into greater depth. They can often work on their own projects in an area they’re interested in, or on a topic combining several subjects. The pupils can work in the same classroom as their classmates this way,” Lenvik says.

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no