Researchers' Zone:

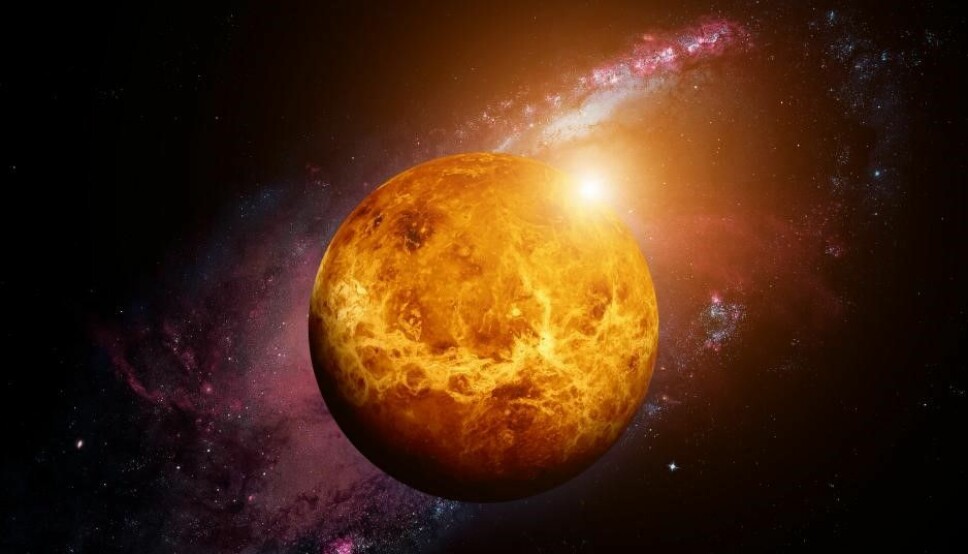

Venus has no moon, yet this moon was discovered in the 1700s

BOOK: How can one discover something that does not exist? Here's the story of the non-discovery of the Venus moon and the planet that never was, Vulcan.

Like all writing of history, the history of science is the history of the victors.

But for every famous scientists we honour for his or her contribution to science’s progress, a large number of lesser-known and often obscure scientists can be found in its authentic history.

What is more, scientific progress has always been hampered by setbacks in the form of incorrect theories and erroneous experiments.

I have written the story of Venus’ moon in two books, an English one titled The Moon that Wasn't and a recently published Danish one titled Den Sære Historie om Venus' Måne og Andre Naturvidenskabelige Fortællinger (‘The Strange History of Venus' Moon and Other Scientific Tales’), where you can read about both the famous and unknown scientists, as well as the major breakthroughs and glaring mistakes.

The title of the book refers to the last category.

We know that the planet Venus has no moon; nevertheless, the moon was discovered many times in observations by competent astronomers.

This is a strange story. How can you discover something that does not exist?

One night at the Round Tower

On March 3, 1764, the observer Peder Roedkiær watched 'the evening star', Venus, through the Round Tower's telescope.

This is something he had done many times, but this night was different.

For, to his surprise, he saw a minor companion or satellite (follower, ed.) that seemed to circle Venus and which, he therefore believed, was a moon circulating around the planet of love.

A week later, in the presence of witnesses, the astronomy professor Christian Horrebow confirmed Roedkiær's observation.

As Horrebow wrote, "Never have I seen in Heaven any vision that has consumed me more, and I believed that I really saw a Venusian moon."

The satellite or moon outlined a semicircle around Venus, and, in a stronger telescope, both the planet and the moon appeared larger, while the background of the fixed stars did not change.

It must, therefore, have been a moon and not a far more distant star that was randomly seen in the telescope’s field of vision.

The two astronomers described their discovery of the ‘Venusian Moon’ in articles for the Royal Danish Society of Sciences and Letters, but because they appeared in Danish, they were barely noticed by astronomers outside of Denmark.

Still, many agreed with Horrebow and Roedkiær that the Venus moon was real.

The Round Tower in the 1700s, with the observatory at the top.

The discovery of Venus' moon

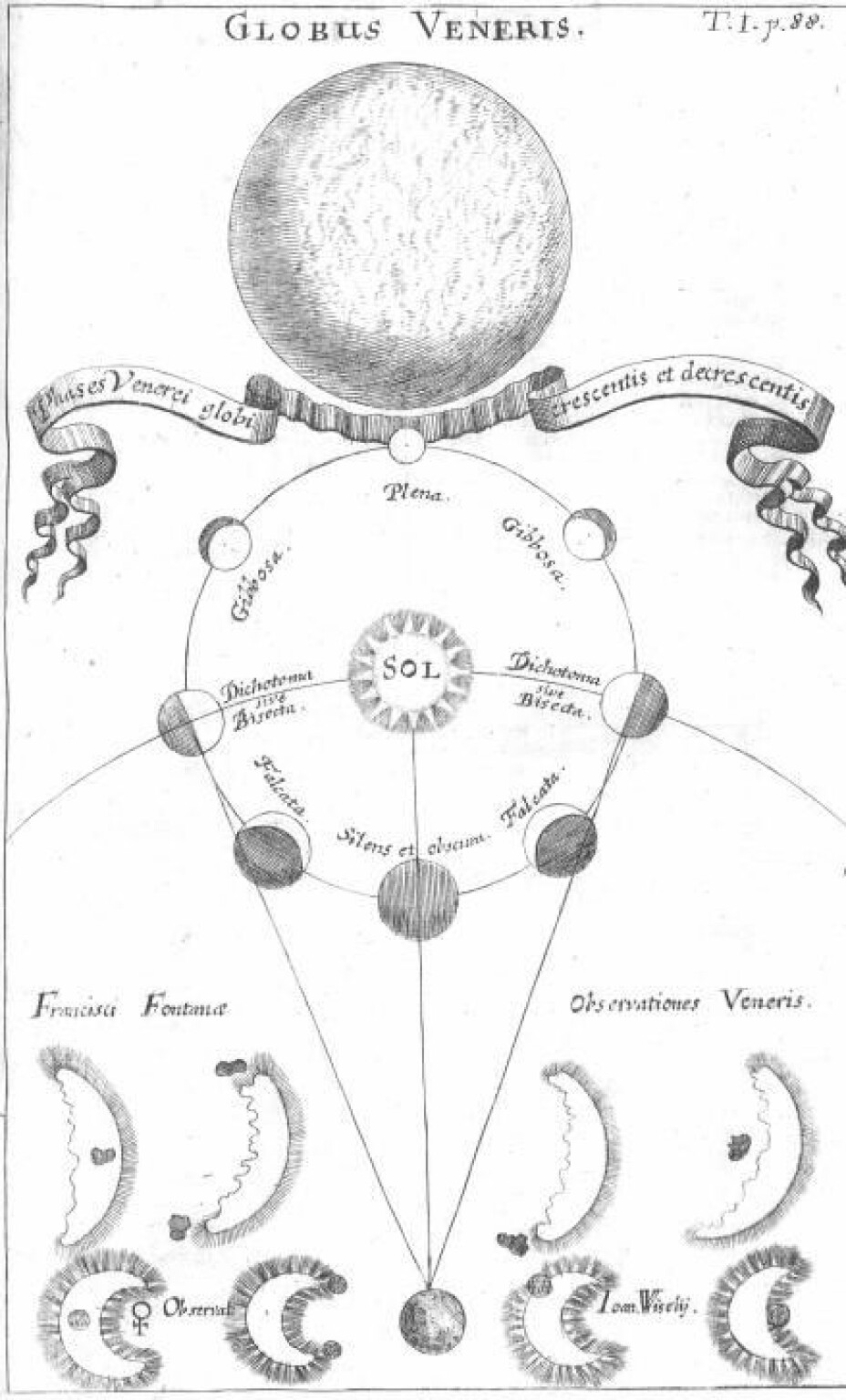

It was neither the first nor the last time that the enigmatic celestial body was observed. The first but somewhat dubious observation dates from 1645, and since then the Venus moon has made its presence felt several times.

In 1761, one of the rare transits of Venus took place, where the inner planet is seen moving across the solar disk in a trip that takes around five hours.

The spectacular event became eagerly studied by astronomers so as to establish the distance between the Earth and the Sun from the transit time.

From the collected data, the figure of 153 million kilometres was established – just 2.3 percent higher than the current figure.

Many astronomers also took the opportunity to look for the moon that might be following Venus.

Most of the astronomers saw nothing, but some did.

Venusians

In 1761, the Frenchman Armand Baudouin was able not only to establish the moon's existence but also its size, time of orbit and distance from the mother planet.

As Venus’ moon was very similar to our own, it reinforced his and his contemporaries’ belief that Venus, too, might be populated with intelligent beings.

Baudouin’s pamphlet entitled 'Mémoire sur la Découverte du Satellite de Venus' (Treatise on the Discovery of Venus’ Moon) caused a stir and was recognised by many as being credible.

The Venus moon was extensively described in authoritative works such as the great French Encyclopédie and the English Encyclopedia Britannica.

It also appeared in the fiction of the time, where it was sometimes represented as a lackey or gigolo that rushed around and attended to the seductively beautiful Venus.

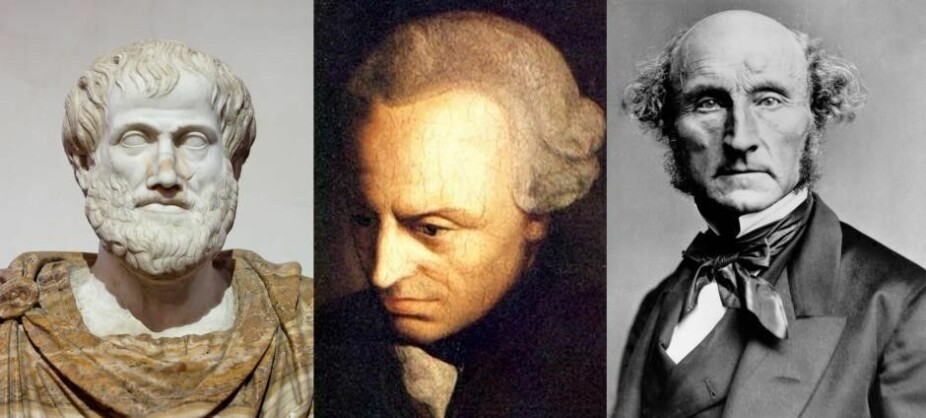

Among those familiar with the Venus moon were the author Voltaire, the philosopher Immanuel Kant and the Prussian King Frederick the Great.

From moon to myth

Over a 20-year period, the Venus moon was popular and enjoyed widespread recognition.

However, many astronomers of the time were sceptical and far from convinced that it was real.

It occupied the grey area between the discovered and the undiscovered.

By the next transit of Venus in 1769, there was no trace of the moon, and by the end of the century, astronomers had written it off as a curiosity – an embarrassing mistake.

Although it had been observed almost 40 times, including by renowned astronomers, it was nevertheless a ghost moon; a phantom.

Hypotheses about the illusion

Now it was a matter of explaining how experienced astronomers had seen a moon around Venus when there is none.

As early as the 1760s, the Austrian astronomer Maximilian Hell came up with the simple explanation that the alleged observations of the moon were nothing more than visions that emerged in the lenses of the telescopes.

Almost 100 years later, Belgian astronomer Paul Stroobant suggested that the observations were in fact due to weak stars in the line of sight to Venus.

Both hypotheses were supported by experiments and calculations, and by combining the two, one could essentially explain the alleged lunar observations.

A perfectly satisfactory explanation for all the previous observations is still missing, but it is not so important now. We can state with certainty that Venus does not have a moon, and nor did it have one in the 1700s.

Not the only mistake

Science is based on observations. If one cannot trust what scientists observe with their instruments, it can seem as if the whole basis for scientific knowledge of the world crumbles.

It is not quite that bad, however, because through critique and repetitions by other scientists, it is almost always possible to distinguish between credible and untrustworthy observations.

That is what happened in the case of Venus' moon, which was weighed up and found to be empty.

In the history of science, there are many other examples of scientists seeing something that does not exist.

For example, in the latter half of the 19th century, there was much interest in the small planet 'Vulcan', which was supposed to be found within Mercury's orbit.

The planet was seen more than 100 times, yet Vulcan has no more reality than the Venus moon.

However, there are differences between the two historical mistakes, because while the temporary belief in Vulcan was justified by a difference between observations and calculations, a so-called anomaly, this was not the case with the Venus moon.

Astronomers in the 19th century considered Vulcan real because they wanted to solve a scientific problem that only found a real solution with Einstein's general theory of relativity in 1916.

By comparison, there was no particular reason to believe in Venus' moon; or even, for that matter, not to believe in it.

For a long period of time, there were just astronomers who thought they could see it and were perhaps a little too quick to interpret the luminous spot in the telescope as a moon.

A full account of the history of the Venus moon can be found in H. Kragh, 'The Moon that Wasn't: The Saga of Venus' Spurious Satellite' (2008) and in a shorter version in the same author’s Danish book Den Sære Historie om Venus' Måne' (2020).

Translated by Stuart Pethick, e-sp.dk translation services. Read the Danish Version at Videnskab.dk's Forskerzonen.

References

'Den sære historie om Venus' måne', Lindhardt og Ringhof (2020)

'The Moon that Wasn't: The Saga of Venus' Spurious Satellite', Birkhäuser (2008)