The majority of researchers in Greenland are foreign. Does it matter?

GREENLAND: The research environment in Greenland is largely comprised of foreigners. ScienceNordic has asked researchers what impact, if any, they believe this has on the nation’s research.

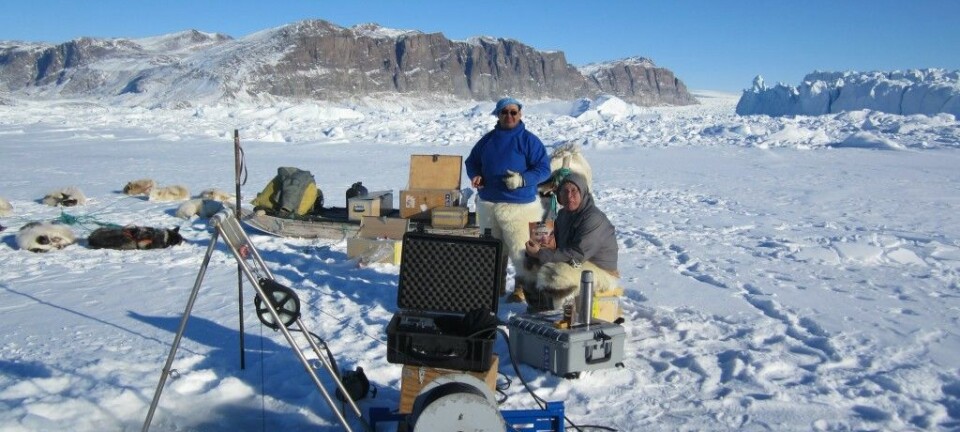

Greenland has great research potential. International research teams flock here every year to take samples, collect ice cores, or set up telescopes and other monitoring equipment.

But it is international scientists who dominate both these short duration field campaigns as well as the majority of permanent research positions in Greenlandic research institutions, including The University of Greenland (Ilisimatusarfik).

But does it matter where scientists come from? And should there be targets to train and recruit native scientists? ScienceNordic asked three researchers who are involved in the Greenlandic research scene to find out.

“Greenlanders don’t feel any ownership over research”

Aviaja Lyberth Hauptmann, Ph.d. student, Department of Systems Biology, The technical University of Denmark.

“I think that lots of foreign scientists means that Greenlanders may perceive that research as representing some other people’s view of how things are. It doesn’t feel like something that they have ownership of. And it’s of course difficult when the research puts issues on the table that Greenlanders will have to deal with. For example, enacting a climate agreement or settling fish quotas.”

Conflict can develop quickly between fishermen and biologists when biologists make recommendations to the Greenland parliament. But the power struggle is even more fraught when the biologists are foreign, says Hauptmann.

“If it were someone’s daughter, uncle or cousin making these recommendations, and not only [foreign scientists], then I think that people would be more inclined to compromise and not simply reject the recommendations from the start,” she says.

“I think the most important thing that you can do to get more Greenlandic researchers is to have a research environment in Greenland for them to be a part of.”

“I’m impressed how well the Greenland Institute for Natural Resources in Nuuk, which I have visited many times, integrate the Danish researchers that move there.”

“But we should also educate more people [in Greenland]. It should be a goal in itself that the local population should also pursue a higher education. But of course there is a limit as to how many can achieve that when the population is just 56,000.”

“Everything in academia is conducted in Danish”

Per Langgård, Senior Consultant at Oqaasileriffik, Language Secretariat.

A side effect of having so many international researchers, is that few of them see their future in Greenland, says Langgård.

“Very few people move to Greenland to retire. I think that’s very important to note. We can’t underestimate that the scientific discussion that we have are far removed from what people talk about on the street, in Nuuk. I think it would make a big difference if we were forced to speak about the communities’ priorities.”

“I don’t really think it means anything if you have light skin or dark skin. I think it’s simply about language and discourse.”

Academic life in Greenland is conducted in Danish or English, which makes it difficult for the rest of the population to understand, if they haven’t fully mastered either language to perfection.

“The vast majority of the population are looking into a foggy shop window and cannot really see what is going on in their own country. And on the other side of that window there are others who are making decisions in a foreign language that they don’t perhaps completely understand. So we really need more people to be educated.”

“Greenlandic science needs to be peer reviewed but the research environment here is so small that there are no Greenlanders who can do it [in their own language]. So they have to publish in English. And this is itself a big problem with communicating research to the population.”

“There’ll be more Greenlandic researchers in the future”

Rebekka Knudsen, project leader of “Greenland Perspectives”, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

“Where you come from doesn’t necessarily matter. But a historian from Uganda will have a different frame of reference and will often have different research interests to a German researcher,” says Knudsen.

Research interests and perspectives can also change when you live in a country that you are studying.

“Research is international, almost by definition. So I don’t think that the goal should be for researchers in Greenland to only be Greenlandic. It’s better to focus on knowledge rather than nationality. But there is a clear interest in developing more home-grown talent--partly to increase the amount of home-grown knowledge, and also so that the knowledge about Greenland is more rooted in that country.”

“There will always be international researchers from many different countries in Greenland. But there’s also a movement towards more education. So naturally, we’ll have more Greenlandic researchers in the future.”

------------------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex