Immigration to Scandinavia:

Will Norwegian and Swedish Social Democrats follow the tough Danish line?

Grete Brochmann believes that the Danes’ latest experimental policy to return refugees to Syria is also an extreme line in the European context.

SThe Norwegian Labour Party could be cruising toward the September election on a tailwind – as long as immigration doesn’t become a hot topic in the election campaign.

Social democrats run into trouble when immigration is high on the political agenda.

“That’s when the Labour Party becomes fuzzy, and the Progress Party steps in and mobilizes parts of the electorate by saying that they’ll take a tougher line,” says sociology professor Grete Brochmann at the University of Oslo (UiO).

Assuming nothing dramatic happens in the world around us in the coming months, Brochmann doesn’t think immigration will be a burning issue in this year's election campaign.

“Very few asylum seekers are coming to Norway now. And often it’s asylum seekers that raise the temperature of the debate,” she says.

Immigration a difficult question

Norway is not the only country where social democratic parties have a difficult relationship with the topic of immigration.

Brochmann believes immigration is a complicated issue for social democratic parties in general, but especially in Scandinavia.

The professor has now contributed a chapter to the book Comparative Social Research.

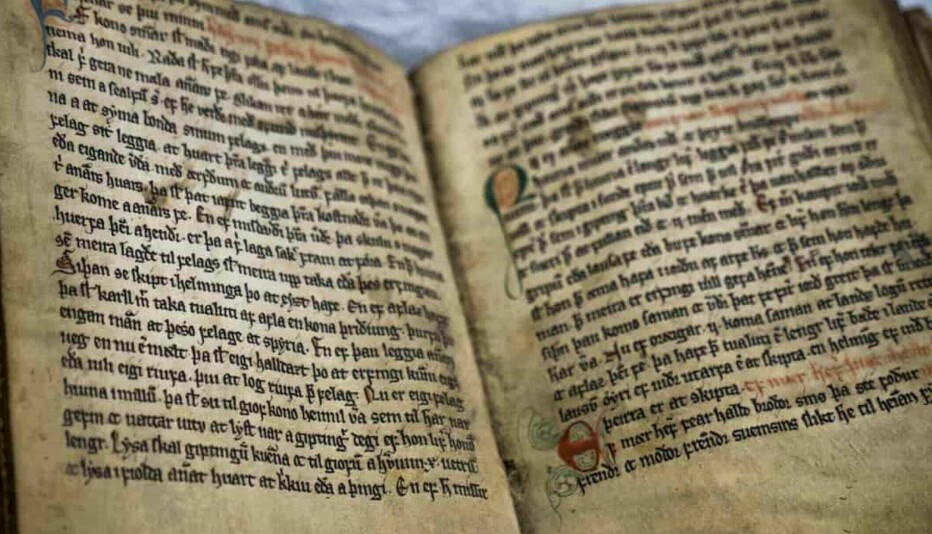

She has been studying the immigration policy of the social democratic parties in Norway, Sweden and Denmark for the past 50 years. She uses historical analysis and document studies in her research.

Different over time

Immigration to Scandinavia began to accelerate in the 1960s and 1970s.

At the time, the three social democratic parties in Norway, Sweden and Denmark had a fairly cohesive policy, Brochmann found in her study.

They would diverge significantly over time.

In the beginning, immigration to Scandinavia consisted mostly of labour migration.

The trade union movement in the three countries came to the fore. A lot of activity revolved around what we today call "social dumping."

“They were afraid that a layer of reserve labour would form in the labour market, and that these new immigrants would contribute to pushing down wages and weakening the rights workers had fought for in the Nordic countries. All three countries introduced immigration regulations in the 1970s to deal with such challenges,” says Brochmann.

As asylum seekers and people seeking family reunification gradually came to dominate the immigration picture, the situation changed.

The political tools that had been implemented were no longer applicable.

Sweden led immigration policy

Sweden experienced fairly extensive labour immigration before Norway and Denmark did.

Swedish Social Democrats thus set the tone for immigration policy in Scandinavia.

In the 1970s, the Social Democrats had been in power in Sweden for over 40 years.

Integration policy in Sweden followed two tracks:

On the one hand, newcomers were to have access to the same rights as those who lived here.

On the other hand, space was to be created for them to preserve their original culture and religious traditions.

Swedish culture toned down

The Swedes created policy that combined entry regulation with equal treatment and integration. At the same time, the Swedish Social Democrats were concerned that immigrants should receive equal pay and equal treatment with Swedes.

But it was also important that Swedish society should not expect immigrants to become "Swedish" in the cultural sense.

Traditional Swedish culture was toned down in favour of values related to democracy and human rights, Brochmann writes in her analysis.

These developments were clearly influenced by ideology, she says.

Politically radical bureaucrats, interest groups and researchers comprised the key actors. Everyone had been inspired by new ideas about value diversity and cultural tolerance.

Denmark clearly more sceptical

From the beginning, Norway closely followed what was happening in Sweden. This was the case until the 1990s, says Brochmann.

“When you read public Norwegian documents, you can recognize wordings that have been directly translated from Swedish,” she says.

Denmark also adopted many of the new ideas from Sweden. But the package that the Swedes developed was much more critically received in Denmark than in Norway.

“Denmark was very sceptical of give up the nation's traditional thinking. The idea of "multiculturalism" did not garner nearly the same attention in Denmark as it did in Sweden and Norway,” says Brochmann.

The Danes opposed special schemes and policies adapted for immigrants.

Swedes were generous

Around the year 2000, immigration policy in the three Scandinavian countries diverged.

In some areas, Sweden and Denmark went in opposite directions.

From 2006, when Fredrik Reinfeldt from Moderatarna (Moderate Unity Party) came to power, Sweden pursued a very liberal immigration policy.

This policy characterized Sweden right up until the refugee crisis in 2015.

By then, the Swedes had received close to 160 000 refugees, with the majority coming from Syria.

But then politics took a significant turn.

Sweden, under social democratic leadership, wanted to signal a much tighter line and position itself as one of the most restrictive receiving countries in the EU.

Since then far fewer refugees have been granted asylum in Sweden.

But compared to Norway and Denmark, Sweden still receives refugees at a high level relative to the country’s population, says Brochmann.

Denmark steadily taking a harder line

Denmark started its restrictive immigration policy already in the early 2000s.

The government of Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen from the bourgeois party Venstre introduced a scheme in 2002 where immigrants – and others having a short period of residence – would no longer receive social assistance.

Instead, they received something called start-up assistance, which involved significantly less support from the state.

Today's Social Democratic Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, has taken this restrictive line forward.

And she is turning out to be taking a steadily harder line.

Recently, 94 Syrians were informed that they will no longer be allowed to remain in Denmark. It is expected that many more will face the same fate in the future, according to NRK, the Norwegian broadcasting company.

Most restrictive in Europe

Today, Denmark – led by the Social Democrats – is pursuing the most restrictive immigration policy among the traditional immigration countries in Europe.

“The Danish Social Democrats have signalled that they want to return to their roots, where basic national values and solidarity have greater significance than human rights and multiculturalism.”

In this way, the party has managed to outmanoeuvre the Danish People's Party, says Brochmann.

The Swedes, led by the Social Democrats' Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, have changed their immigration policy since 2015.

“They introduced border controls and wanted to join the most restrictive line in the EU - especially when it comes to temporary protection and allocating rights,” says Brochmann.

This move was intended as a temporary solution, after the refugee crisis, to signal that Sweden is no longer the liberal asylum country in Europe.

Debate in Sweden has also changed

Since 2015, several temporary schemes in Sweden have been made permanent, Brochmann says.

Before the summer holidays, the Social Democrats will implement a new migration law for Sweden.

“Hardly anyone believes that the country will return to the state before the refugee crisis in general. The public debate in Sweden has also changed. The strong growth of the Sweden Democrats is a clear message that parts of the population in Sweden feeling the need to tighten immigration policy,” says Brochmann.

Populism came late to Sweden

The Norwegian Progress Party was established in 1973 and under party leader Carl I. Hagen created a clearer stance against immigration from the late 1980s.

But in Denmark, a party with exactly the same name had already in the 1970s marked itself as critical of immigration.

This contributed to immigration becoming a politicized topic in Denmark at an early stage – including for the Danish Social Democrats.

Brochmann points out that Denmark is also more ideologically nation-oriented in immigration policy than either Sweden or Norway.

In Sweden, immigration was initially less politicized and to a greater extent an expert-driven topic compared with the approach in Denmark and Norway, says Brochmann.

Then Sweden Democrats came on the scene

The anti-immigration party Sweden Democrats crossed the 4 percent threshold necessary for parliamentary representation in the 2010 election. In the 2018 election, the party became the third largest party in Sweden.

A lot has changed.

Brochmann finds it interesting how much more "immigration-friendly" the public debate has been in Sweden compared to Norway, and especially compared to Denmark.

“The difference shows the extent to which public discussions are national discussions,” she says.

“The debate climate is significantly different in the three Scandinavian countries, not only when it comes to immigration, but also on other issues. That’s been the case for a long time.”

Norway found intermediate position

Norway’s Labour Party has placed itself somewhere between its Swedish and Danish counterparts, and has been inspired by both, Brochmann believes.

She points out the Labour Party became more divided in its view of immigration as the number of asylum seekers increased starting in the late 1980s and the Progress Party grew from the 1990s onward,.

Norway has quite clearly wanted to place itself in the middle on immigration policy. But has the country started to become inspired more by Denmark?

“Norway has increasingly begun to look at what Denmark is doing in welfare policy, especially since the Solberg government took over,” Brochmann says.

But what will happen next if the Labour Party forms a government in the autumn, is uncertain, she says.

Brochmann believes that both Stefan Löfven in Sweden and Jonas Gahr Støre in Norway are closely following what is happening in their Danish sister party.

However, she does not think that Norway’s Labour Party will adopt the restrictive swing seen in Denmark.

“The immigration policy that commanded a majority at the previous Labour Party national meeting contains some of the same thinking. But this does not mean that they’ll follow in Denmark’s footsteps. What’s happened in Denmark under Prime Minister Frederiksen's government is a rather extreme turn, especially in asylum and refugee policy,” Brochmann says.

Danish social democratic success

Across Europe, social democratic parties are facing headwinds, with one big exception: Denmark.

Purely in terms of recent elections, the Social Democrats under Frederiksen have been successful, according to UiO political scientist and researcher Peter Egge Langsæther. He finds the developments in Danish politics very interesting:

“Mette Frederiksen has succeeded in turning the tide. She addresses the Danish working class directly. She told voters who left them in favour of the anti-immigration Danish People's Party, ‘It isn’t you who have failed us. We’re the ones who have failed you.’”

The turnaround operation has led to Denmark having the most socialist parliament in decades.

Managed to gather the troops

The turnaround operation of the Danish Social Democrats involves introducing a restrictive package of reforms in immigration policy and in immigrants' access to welfare benefits at the same time.

In terms of welfare policy, they are trying to make the gateway for immigrants much narrower than before.

Brochmann believes these actions are taking place because many Danes basically do not want immigration of refugees.

Combining a strict immigration policy and a more classic social democratic social policy has struck a chord with Danish voters.

“Her policy is strongly heard in the part of the population that Frederiksen appeals to. But she has also managed to rally party members to support the platform on which she won the election.”

“Since the election, she’s actually ramped up immigration restrictions. In the most recent turn of events, Denmark is revoking residency permits for Syrians through testing out a return policy. Brochmann points out that this is regarded as an extreme line in the European context.

What about the voters?

Who votes for the social democratic parties in Denmark, Sweden and Norway today?

The electorate of most social democratic parties is an alliance of workers and a number of new middle-class groups. The latter can include anyone from sociologists to teachers and professors, says Langsæther.

The major problem for the social democratic parties lies precisely in that their voters are so wide ranging socioeconomically.

“Voters agree on the economic redistribution policy for the most part. But they don’t agree on value issues. Most such parties have lost supporters by being liberal on various value issues, such as immigration.

Langsæther therefore thinks it unlikely that Støre will follow in Frederiksen's footsteps.

Labour Party remains the Workers' Party

The Labour Party is still the most popular party among Norwegian workers, Langsæther says.

The support for the party in this group is around 30 percent. According to the Norwegian Election Survey 2017, this is the societal group that is least positive about immigration.

Ahead of this autumn's parliamentary elections, the Centre Party and the Progress Party probably constitute the biggest challengers to the Labour Party in the battle for voters. Both can focus a lot of this year's election campaign on district politics.

Langsæther thinks it’s interesting that the Labour Party is now trying out some of the same tactics with Norwegian district policy that Frederiksen succeeded with in Danish immigration policy: to take the policy – and the voters who follow – back from the challengers.

Working class immigration scepticism

Langsæther says the anti-immigration stance of the working class has been explained in different ways.

“Some people point out that workers are more exposed to competition from immigrants, both in the labour market and when it comes to access to welfare services.”

“Others name xenophobia and prejudice as reasons. They suggest that these attitudes may be related to educational level or even cognitive abilities,” says Langsæther.

Heated debate

Langsæther notes that anti-immigration sentiment is now undergoing heated international debate in academia. People are also discussing whether support for right-wing populists is linked to the economy or whether it has more to do with culture.

“I don’t think there’s any one explanation. I also find it prejudicial to assume that other people hold certain attitudes because they’re less smart than we are. We need to have good empirical evidence to say something like that.”

Langsæther thinks a big and interesting question is whether higher education makes people more understanding about immigration.

“Or is it rather that it is the groups that are most positive about immigration pursue the most education?” he asks.

“A third possibility is that people who pursue higher education mostly end up in different socioeconomic strata than those with less education and thus have different interests related to immigration,” Langsæther says.

Translated by Ingrid Nuse.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no.

Refrence:

Nik Brandal, Øyvind Bratberg and Dag Einar Thorsen (eds.): Social Democracy in the 21st Century, Comparative Social Research