Immigrant teens drop out of sports to focus more on school

More young people in Norway are prioritizing school and dropping out of sports – but that only applies to immigrant youth. For everyone else, the opposite is true.

“One important reason why immigrant youth don’t participate in sports clubs is that they’re spending more time on school work. Norwegian adolescents don’t find school work an important reason to drop sports,” says Mads Skauge.

Social differences

Skauge is a PhD candidate at Nord University and will soon complete his doctorate focusing on social inequality in sports participation. He has looked at the differences between teens who participate in sports and those who do not. Socioeconomic disparities play a role, but the differences also run along other lines, such as gender and ethnicity.

Skauge states that the main reason immigrant youth quit sports clubs is school work.

When he talks about “immigrant youth”, he is thinking of young people who were born in Norway but have two parents who immigrated – a population group that Statistics Norway describes as “Norwegian-born to immigrant parents”. He used Ungdata figures from the Norwegian Social Research institute (NOVA) as his starting point.

School and sports complement each other…

“Looking at Norwegian teens first, we see that the better their school performance, the more time they spend on homework, and the more engaged they are in school, the greater the chance that they also participate in sports. It’s the complete opposite for immigrant youth,” says Skauge.

He describes how school and sports are connected and complement each other for ethnic Norwegian youth. He thinks this may be due to the fact that school and organized sports have some similarities. Both are led by adults and both are performance-based. In both settings you have to work purposefully over time to succeed.

“If you master the one, you’ll probably master the other, too. The way you get good at math and the way you get good at handball are the same,” he says and points to how systems, adults and discipline are involved in both.

… but not among immigrant youth

The question is why immigrant youth don’t experience sports and academics in the same way. Skauge believes that they experience the two as competing with each other rather than complementing each other. In this group, the most motivated teens with the best grades tend to focus on academics and quit sports.

“Lots of studies show that immigrant youth are generally more motivated at school. This phenomenon is often explained by the fact that they’ve come to a society where youth have every opportunity, and their family is supportive. Often the parents of immigrant youth didn’t have the same opportunity themselves. These teens’ education – especially in high school when grades start to count – becomes more of a ‘family project’", Skauge says.

Sports take more time when children become adolescents. Training, competitions and travel increase. School also requires more time – at least for pupils who have the greatest ambitions.

Choose to quit themselves

Skauge points out that immigrant youth are not a uniform group in this context. Dropping out from sports is especially evident in young people of Asian origin. The pattern is much more evident for a youth with Pakistani parents than for one with Swedish parents, for example.

“What our studies show is that kids who leave sports aren’t quitting because they feel excluded. They just opt out. Teens quitting sports isn’t the young people’s problem. It's more a problem of the sports organizations, who aren’t managing to keep the youth,” says Skauge.

Continue to train

He points out that just because young people stop doing organized sports doesn’t mean they stop exercising. They keep training but manage their time and activity themselves – at gyms or out in the woods and fields. They need flexibility, whereas organized sports have much more set schedules.

“Keeping young people active is the most important thing for public health. But the sports clubs’ position will weaken if their members disappear,” says Skauge.

Alarming membership decline

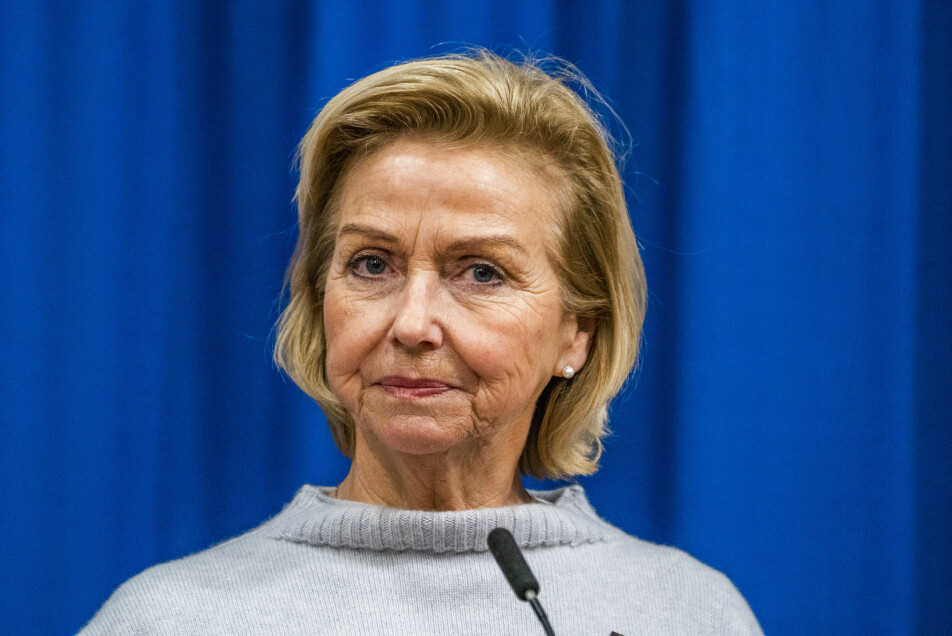

That is something the Norwegian Confederation of Sports (NIF) is also woefully aware of. NIF president Berit Kjøll says that Norwegian sports have lost 10 percent of their members during 2020 and calls the situation “alarming and serious”.

Declining sports participation “impacts the conditions of growing up in local communities around the country and poses a significant public health challenge. It’s absolutely crucial to quickly reopen all the Norwegian sports clubs,” Kjøll says in a press release about the numbers after the past coronavirus year.

Worried parents

Professor Åse Strandbu at the Norwegian Sports Academy talks about research from a while ago that points to findings similar to Skauge’s current results. Fifteen years ago, Strandbu wrote the book Idrett, kjønn, kropp og kultur: minoritetsjenters møte med norsk idrett (Sports, gender, body and culture: minority girls' encounter with Norwegian sports).

“A number of parents of minority girls were a little worried that sports activity would affect school work. The majority of ethnic Norwegian parents, on the other hand, thought that school and sports reinforced each other and that doing sports was beneficial for school results too,” says Strandbu, who stressed that it’s been 15 years since she conducted her interviews on the topic.

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Mads Skauge and Arve Hjelseth: Organisert idrett og skole som komplementære og konkurrerende arenaer: ulike mønstre for minoritets- og majoritetsungdom? (Organized sports and school as complementary and competitive arenas: different patterns for minority and majority youth?) Nordisk tidsskrift for ungdomsforskning, May 2021, doi: 10.18261/issn.2535-8162-2021-01-02