Helicopter technology to solve Indian water shortage

Danish scientists have developed a special technology which uses a helicopter to locate groundwater. The technique is currently being used to search for clean drinking water in India.

A helicopter equipped with Danish technology is currently hovering over India. The objective is to map the subsoil and figure out how to solve a massive problem for India’s more than one billion population: the lack of clean drinking water.

”In India there are massive problems with water supply. The groundwater resources currently available are often polluted or overexploited, which means that a great number of people have trouble getting clean drinking water,” says Professor Esben Auken, of the Department of Geoscience at Aarhus University.

He is one of the Danish researchers who have just flown off to India to start a survey of India’s groundwater resources.

Generating underground electricity

The pilot part of the project will focus on six areas in India, where the subsoil will be surveyed as far down as 300 metres below sea level.

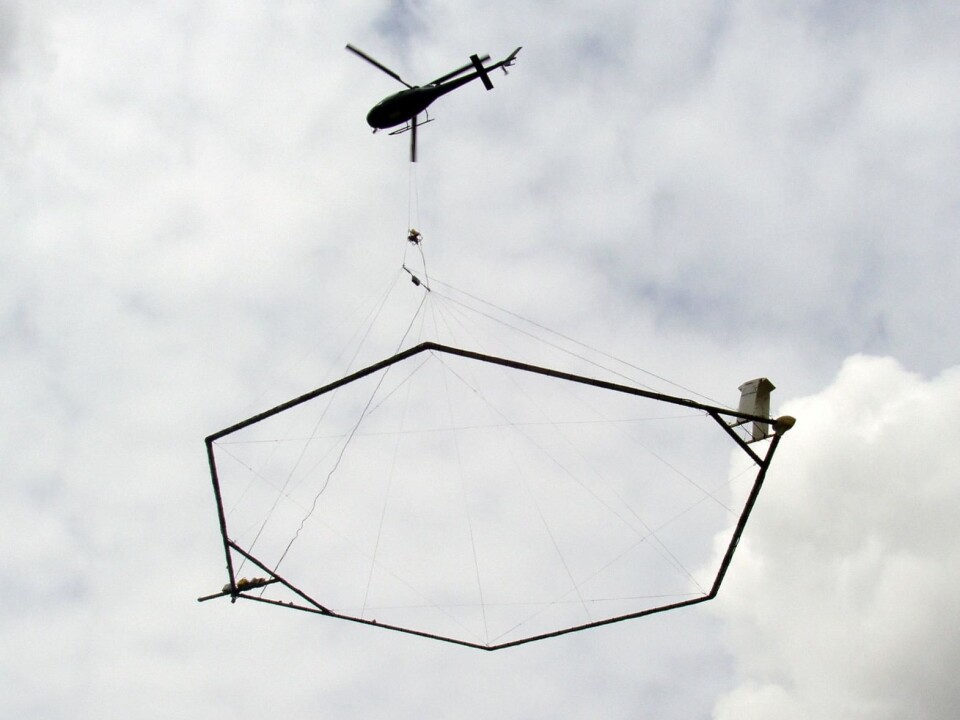

The technology, known as SkyTEM, makes use of a large ring, similar in appearance to a fish farm cage, measuring approx. 300 square metres. The ring is stretched out under a helicopter and acts as a giant coil which is powered by a generator.

“The electrical currents in the ring that hangs from the helicopter create a very powerful electromagnetic field. If you turn off the current, the magnetic field changes very rapidly. And when you change a magnetic field, you induce a current into the environment. So the electromagnetic field in the ring enables us to get an electrical current to flow in the subsoil,” says Auken.

A 3D image of the subsoil

The current generated in the subsoil will behave in different ways, depending on whether the helicopter is flying over bedrock, clay or sand. Or rather, the type of subsoil determines how quickly the current decays.

”We will be utilising this fact with a sensor on the ring, which measures the decay of the magnetic fields generated by the currents,” says the professor.

Analyses and mathematical models of these measurements will then inform the researchers of the contents of the subsoil.

“We will be flying in straight lines above the ground. Our scans provide us with lots of data, which we will use to create a three-dimensional image of the subsoil.”

Based on analyses and data from the helicopter, they can then figure out where the groundwater is located.

A potential export success for Danish technology

The pilot project with the Danish SkyTEM technology is carried out in collaboration with the Indian National Geophysical Research Institute in Hyderabad. According to Auken, the new technology has the potential to become part of an extensive nationwide project that aims to find a sustainable solution to India’s problems with water shortage.

“We will of course be trying to convince the Indians that our method can solve the great problem of finding groundwater,” he says.

“If our surveys of the six areas covered in our pilot project are successful, our technology may become part of a huge project which will create a nationwide survey of the Indian groundwater supply. If that’s how things turn out, then we’re looking at a potential export success for Danish technology and know-how.”

The SkyTEM technology saw the light of day in 2000, and the research has formed the basis of the company SKYTEM Surveys.

“Our technology has already been used in most parts of the world. We have been involved in major projects in Antarctica, Australia, South Africa, the US, Canada and in several European countries. So we know that it works well, but our models and our software need to be adapted to local conditions. That’s our job as researchers: to develop and refine the technology.”

The pilot project in India forms part of the 'Heli-borne Geophysics for Aquifer Mapping' (AQUIM) project, which is funded by The World Bank and the Indian government, and is administered by the Central Ground Water Board, Delhi.

-----------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther