Grizzly-polar bear hybrids spotted in Canadian Arctic

Call it a 'pizzly' or a 'grolar bear', this new hybrid may be here to stay, say scientists. But is this the end to the polar bear as we know it or the start of a new bear species?

Meet the Pizzly, or should that be Grolar Bear? These unusual looking bears, which are a mixture of polar bear and grizzly bear, have been popping up around the Canadian Arctic since the first reported shooting in 2006.

Eight further sightings have followed and were confirmed as polar-grizzly hybrids by DNA testing. A ninth sighting is now awaiting the results of a DNA analysis before that too can be confirmed as a hybrid.

The bears essentially look a little bit like mum and a little bit like dad, with cream or light tan fur, intermediate claws, a slender polar bear snout, and the broad, muscular shoulders of a grizzly.

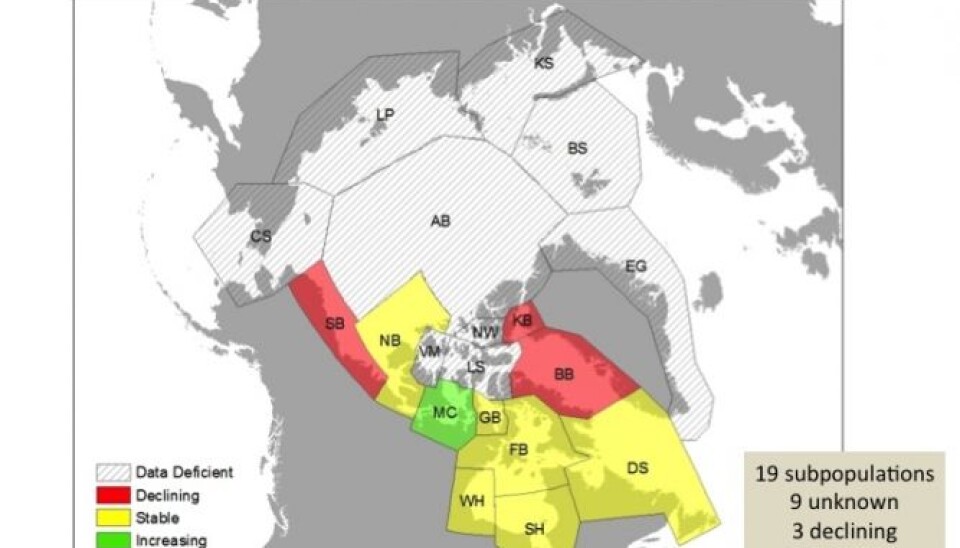

“We’ve known for a long time that hybrids between polar bears and grizzly bears were possible. We’ve known from zoo studies in Europe that you can take a male and female from either species and hybridise them, and that their offspring are fully fertile,” says polar bear scientist Andrew Derocher, from the University of Alberta, Canada, who studies polar bear populations in the Canadian Arctic and Hudson Bay.

“To date, all the confirmed hybrids are in Canada. But that doesn’t mean that they couldn’t exist in Russia for example, where these species come very close to each other, or in Alaska, where they also overlap,” he says.

See what the hybrid bears look like in the gallery above.

Grolar bears a result of climate change

Climate change is in part responsible for the emergence of these grolar hybrids, as polar bears that live and hunt on the ever-shrinking Arctic sea ice are forced on land during mating season in spring and summer.

At the same time, male grizzly bears are expanding their habitats, roaming into polar bear territories, and emerging from hibernation earlier in the year.

Inuit hunters have spotted grizzly bears in the Arctic for decades, but numbers are believed to have increased recently, causing males to disperse further in search of a female.

The result is that where the two species meet, they mate, says Derocher.

Genetic similarities allow cross breeding

Interbreeding between two closely related species is nothing new, says evolutionary biologist Eline Lorenzen, from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. All it takes is for two species or sub-species that were separated for a period of time to be brought back into contact. So long as they still have enough genetic similarities, they can mate and produce fertile offspring. And we only have to look at our own species for evidence of this.

“Neanderthals living in Eurasia and Homo sapiens in Africa are a good example. They diverged for a couple of hundred thousand years and then came back into contact. Now all human populations outside of Africa carry a genetic signature from Neanderthals,” says Lorenzen.

“So in our own species, hybridisation and borrowing genetic material from another lineage that allows you to adapt to your environment, has occurred before,” she says.

Read more: Oldest human genome reveals a story of sex and migration

Polar bears and grizzlies have interbred before

Studies of bear DNA shows that polar bears and brown bears have also interbred before, says Lorenzen, who has previously mapped the genome of 89 polar bears. She discovered that polar bears and brown bears first diverged as a species between 479,000 and 343,000 years ago.

Since then, the two species have met and interbred several times, and today, brown bears (also referred to as grizzly bears) still retain some of this ancient polar bear DNA, and vice-versa.

“So the fact that species are mixing is not unique in any way. But what is unique now, is that there is a very real chance that a large portion of Arctic sea ice is going to disappear relatively rapidly, and so we will see many more examples of the two species meeting than has been the case before,” says Lorenzen.

Read more: Arctic sea ice is at a record low

The polar bear’s unique set of genetic adaptations could be lost

Some of the recent pizzly sightings in Canada are now second generation hybrids, dominated by grizzly DNA.

“When I say hybrids I’m referring to half polar bear and half grizzly bear. But I know of four individuals that are three quarters grizzly and one quarter polar bear. So we have a hybrid mating with a grizzly bear and we get a second generation that is three quarters grizzly,” says Derocher.

The dominance of grizzly DNA is a concern to both Derocher and Lorenzen, who suggest that polar bears’ unique genetic traits that allow them to live on sea ice and survive on a high fat diet of seals, might ultimately lose out to the dominant population of grizzlies.

“Ultimately, one species will be integrated into the other, and it’s likely that it will be polar bears that integrate into brown bears,” say Lorenzen.

“As polar bears are forced to go on land and interbreed with brown bears then the selective pressures for being able to metabolise fatty acids--that polar bears need--won’t be important any more. So these will likely be lost. Now if that’s your definition of a polar bear then that will be lost as well,” she says.

No new species of bear expected any time soon

So could these hybrids and their offspring become a new species?

Until now, they have been considered more of a scientific curiosity, but they are receiving more attention as their numbers continue to rise.

“The big question now is how these hybrids live,” says Derocher, and right now this is anyone’s guess.

“The first hybrid lived a more terrestrial lifestyle. But I’ve seen from as early as 1986 and most recently in 2013 and 2014, male grizzlies on the sea ice, much further away from where we’d expect to see them and well into polar bear territory. It looked like it was hunting seals, which it wouldn’t normally do,” he says.

But asked whether they expect a new species of bear to arise any time soon, both Derocher and Lorenzen say, no.

It would take somewhere in the order of hundreds of thousands of years for a new species to arise, and it certainly could not occur within our life times, says Lorenzen.