Opinion:

Women sentenced to prison in Norway are treated favourably

OPINION: Contrary to popular belief, women sentenced to prison in Norway receive more beneficial measures than men aimed at reintegration into society. The general claim that women sentenced to prison in Norway are discriminated against, is a myth.

A Google search on the internet for women’s prison conditions results in several Norwegian articles suggesting that conditions in prison are worse for women than men. The Public Services Ombudsman recently published a report on women’s prison conditions. The report states categorically that women in general experience worse prison conditions than men do.

In order to reach substantiated and generally valid conclusions about the differences between the sexes however, it is necessary to compare similar conditions for both sexes. Ideally, one should look at data for the total prison population or at least data from representative samples.

In addition, you need to take into account important differences in sentence length between the sexes. The average sentence for imprisoned men and women is approximately eleven months and six months, respectively. Only 6 per cent (95 prisoners) of those who served a prison sentence exceeding six months in 2018 were women.

- Read Åshild Marie Viges answer to this opinion piece: Both women and men are vulnerable in prison

More men lack activation

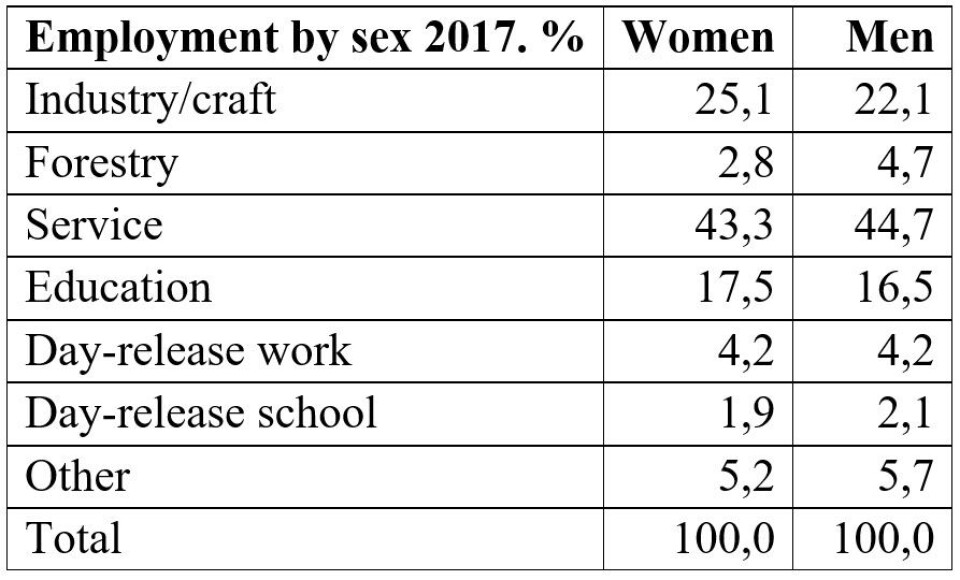

Activation of prisoners is perhaps the most important indicator of any differential treatment of inmates by sex. The Correctional Service registers the number of days in which prisoners are employed.

The numbers from 2017 show that differences in the gender proportions within the various registered activities, such as industry, crafts and services, are small. Women get slightly more education. There are more men working in forestry. Daily exits from prison to go to work or school show practically equal shares for the sexes.

The proportion of prisoners who lacked activation, however, is not included in these numbers. 20 per cent of male prisoners versus 13 per cent of female prisoners lacked activation. Given that men in general serve longer sentences, the opportunity to provide them with employment or education should be better than for women. This finding is therefore surprising.

Women get more leave of absence

Leave of absence from prison is an important measure making a gradual reintegration into the community more feasible before release. Surprisingly, female prisoners get more leave than men do, despite the fact that they generally spend less time in prison.

The proportion of registered days of leave per 1000 prison days was 29 per cent higher for women than for men in 2017. Ordinary leave of absence can only be granted after serving at least four months of a prison sentence. Considering that a higher proportion of men accordingly are entitled to such leave, one would expect the opposite result.

On the other hand, women’s crime type distribution varies somewhat from imprisoned men, and it is likely that a larger proportion of women serve at longer distances from home. It is also possible that more men have further unsettled criminal charges against them. Such factors may have contributed to a more positive assessment of the women's leave applications.

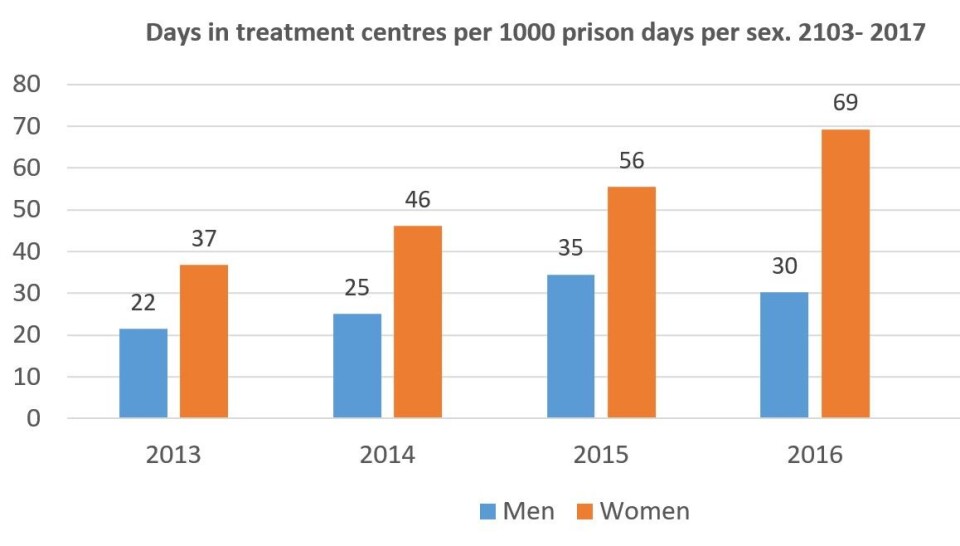

Women receive more treatment for substance abuse

The Ombudsman claims that women have lesser access to substance abuse treatment in prison. Conversely, 12 per cent of those admitted to substance abuse units inside prison were women even though women accounted for only 9 per cent of all admissions that year. Moreover, corrected for total time in prison per sex, women are offered a higher proportion of drug treatment outside prison, and the proportion has been increasing in recent years.

The difference between imprisoned men and women may partly be explained by the seemingly accepted view that substance abuse problems are more frequent or possibly more severe among women. However, recent research in Norway can neither support nor oppose this hypothesis (Bukten et. al. 2016). Overall, there is little evidence that there are significant differences in substance abuse between imprisoned men and women in Norway.

No discrimination in access to programs

Shorter stays in prison limits the ability to offer crime or drug programs to women. If we set a limit of at least six months' residence time in prison in order to be considered for program participation, about 20 per cent of women imprisoned for six months or more in the years 2010 – 2014 started a program, compared to around 19 per cent among the men.

More women in low-security prisons before release

An important objective for the correctional service is to be able to offer a gradual progression to more lenient conditions, meaning access to low security prisons in due time before release, especially for those with longer sentences. 75 per cent of all women released in the years 2010-2014 were released from a low-security prison, compared to 65 per cent for men. The difference can be partly explained by the fact that men serve longer prison sentences and possibly more often for crimes that are more serious. Notwithstanding this, 25 per cent of the released men were released from a high security prison, compared to only 15 per cent of the women.

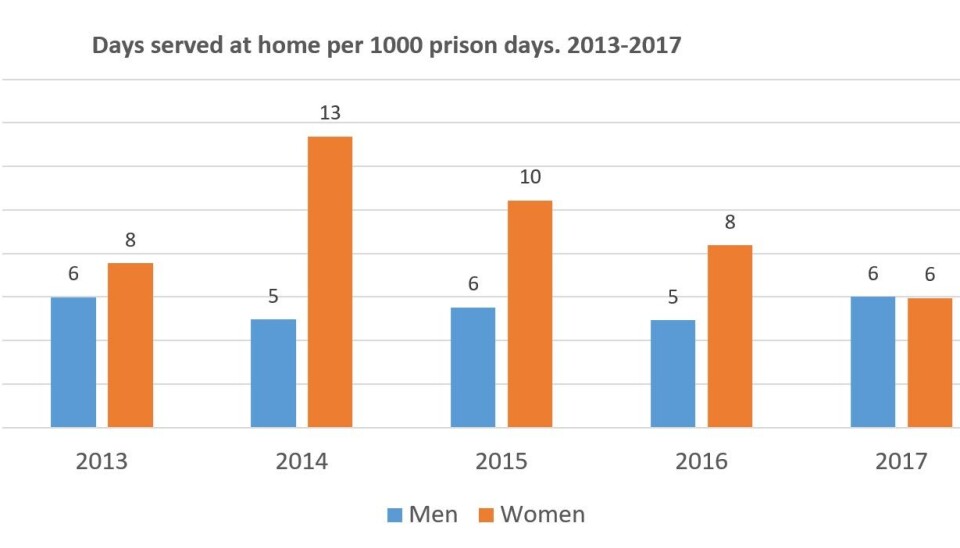

More women serve their sentence at home

Serving a part of a prison sentence at home without electronic monitoring implies that you can stay in your home until ordinary release would have happened. The proportion of women being granted this attractive measure is higher than for men when corrected for the total time served in or outside prison. The proportion has admittedly decreased in recent years to a more equal level between the sexes.

The entire prison sentence can be served at home with electronic monitoring if the prison sentence is four months or less. A comparison of prison sentences of up to four months in 2017 shows that 61 per cent of the female prisoners were allowed to serve the entire prison sentence at home with electronic monitoring. For men, this was only 42 per cent. The difference can be partly explained by a larger proportion of shorter sentences among women and possible differences in risk assessment of breach of terms. Still, the figures show that a considerably larger proportion of women are given the opportunity to serve short prison sentences outside prison.

A need to focus on conditions for male prisoners

To sum up, the numbers show that a significantly smaller proportion of men get activation during imprisonment. Women get more substance abuse treatment, more access to leave of absence, more access to low security facilities and to serving parts or all of their prison sentences at home.

To some degree, these differences can be explained by the perceived severity of crime and differences in assessments of risk or individual needs, possibly related more often to women, such as serving in a prison at long distance from home.

In addition, we probably need a cultural explanation. For more than forty years, the dominant narrative about discrimination in Norway has been the discrimination against women. Despite many years of full legal equality between the sexes, the Equality and Discrimination Act still states that the law specifically aims to improve the position of women. Working for the improvement of women’s position has been an integral and internalized part of the Norwegian culture for so many years that we cannot rule out that this more or less consciously plays an important role in the treatment of women sentenced to prison. This may explain to some extent why women are treated more favourably.

These findings do not deny that women can, in some prisons, experience inadequate or even inferior conditions compared to men, as the Ombudsman has pointed out. However, there is no doubt that many male prisoners also serve in inadequate, dilapidated prison units with unsatisfactory facilities that need to be improved.

References:

Bukten, A. et. al. (2016), Rusmiddelbruk og helsesituasjon blant innsatte i norske fengsel. Report 2/2016. Senter for rus- og avhengighetsforskning (SERAF). University of Oslo.

Sivilombudsmannen, Kvinner i fengsel. En temarapport om kvinners soningsforhold i Norge. (undated)

Share your science or have an opinion in the Researchers' zone

The ScienceNorway Researchers' zone consists of opinions, blogs and popular science pieces written by researchers and scientists from or based in Norway.

Want to contribute? Send us an email!