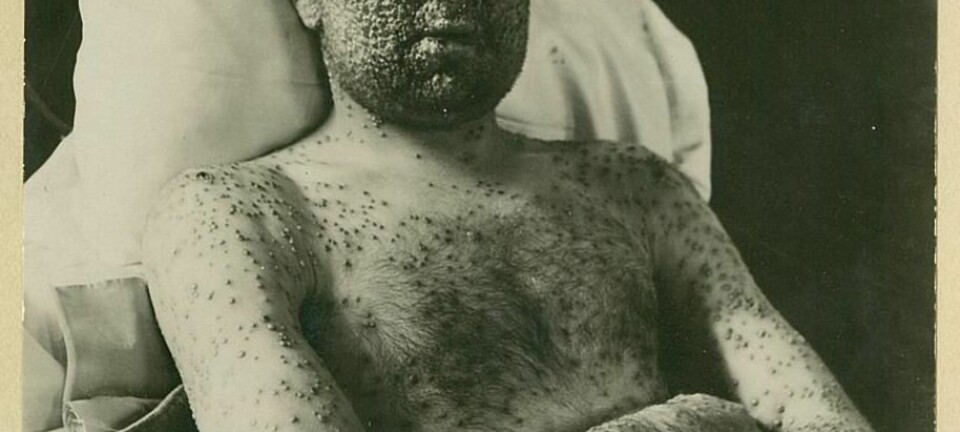

One cough away from a TB epidemic?

Tuberculosis is gaining territory in Europe. Could TB become a major problem again in Norway?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“Tuberculosis is making headway in Norway. From 1996 to 2013 the number of new registered cases doubled,” says Trude Arnesen, chief physician at the Norwegian Institute for Public Health’s Division of Infectious Disease Control.

Norway almost managed to stamp out the disease with improved standards of living, better nutrition and more spacious housing, frequent examinations of the population and the use of antibiotics, including the vaccination of all school children with BCG (short for bacille Calmette-Guerin) as of 1947.

Although the disease mainly infects the world’s poor, it is making a comeback in the richer countries. The outbreak is happening in the Nordic coutries’ European neighbourhood. London has been given the unfortunate reputation of being Western Europe’s tuberculosis capital.

Worried about infection

The preliminary figures for last year show 408 cases of tuberculosis in Norway. Most of these patients had been infected for considerable time before the disease broke out.

“We can once again face a problem with tuberculosis if we fail to follow up with disease prevention initiatives,” warns Arnesen.

“We are worried about new infection. So far we have little new contamination in Norway, but it happens,” she says.

Tiny problem in Norway

Tuberculosis is definitely not invading Norway, asserts Gunnar Bjune, a professor at the University of Oslo’s Institute of Health and Society.

“This is a very minor problem,” Bjune assures us.

He thinks part of the reason for the high incidence in London is that the city has several districts with poor living conditions where lots of immigrants live and who hail from countries with higher TB rates. If that were the case in Norway, he thinks the potential for an outbreak would be seen in this country too.

The rise of TB in Norway is primarily attributed to globalisation. More than eight out of ten cases cropping up are diagnosed among immigrants who brought the disease with them from another country.

TB cases are rising in Eastern Europe too, where many of Norway’s immigrants are from. The disease is also widespread in Africa and Southeast Asia.

A few people born in Norway also catch tuberculosis. Many of them are elderly who have been carriers for over 50 years, since the era when TB was still common in Norway.

Fewest infected in the world

Norway is still far from seeing tuberculosis regain its former dominance as a common public health hazard.

“Norway is one of the countries with the lowest number of TB patients, just seven per 100,000 capita,” explains Arnesen.

Unlike poor countries, sufficient resources are available to give those infected good treatment with antibiotics. Those who are infected are given pre-emptive treatment to keep the disease from developing.

“People who get tuberculosis in Norway can expect to be cured,” says Arnesen.

Slow diagnostics

On the average, Norwegians visit a doctor after a sickness fails to go away after two weeks. But according to Bjune, it takes two months to get a correct diagnosis and start treatment of tuberculosis.

“In 75 percent of the cases TB is not diagnosed during the patient’s initial contact the health services. We are no better in this respect than they are in poor countries.”

“The physician will often prescribe medications for something else, which delays the correct diagnosis. This is harmful because the infection can spread in the meantime,” says Bjune.

Bjune is participating in a study to find out if a simple test at the doctor’s office can help. The test could possibly determine easily whether patients with lingering coughs should be referred to further examinations to see if they have TB.

Airborne bacteria

In principle we can be infected anywhere.

“Incidental infection can happen on a tram, in a shop or other places where we meet people. The bacteria are carried by air, through coughing and spit when we talk,” says Bjune.

“But tuberculosis is not particularly infectious. On average, each person with infectious tuberculosis will only be the source of one new case,” he adds.

End of universal BCG vaccination

Several generations of school children have gone round dreading being vaccinated with what was considered the biggest needle of them all: the one for BCG vaccine.

The day of the mass vaccinations with it in Norway are over – BCG is only given to risk groups.

With tuberculosis making headway, why was the vaccination of the general population halted in 2009?

“A thorough study showed that there was little benefit from it,” says Arnesen.

With so few cases it was considered too costly to vaccinate everyone.

Besides, the vaccine only worked to a limited extent.

“It’s a matter of debate how effective it is. It protects children from falling ill with the most serious forms of tuberculosis, but it has no certain effect for people over the age of 35,” says Arnesen.

Bjune adds that the BCG vaccine does not prevent infection, either.

“We have accepted that the BCG vaccine does not stop the outbreak of tuberculosis,” he says.

Many children the world over are still being vaccinated with BCG. But the development of new vaccines is where the focus is.

Bjune says that at least 14 vaccines are under development right now worldwide. It’s hoped that at least one of them will work better than BCG.

“I am rather pessimistic, as it is hard to invent the right vaccine and get it into use on a global basis,” he says.

Unrealistic goal

The UN’s millennium goal was to stop the spread of tuberculosis. Norway’s official goal is to wipe it out.

But neither Bjune nor Arnesen think this realistic.

“Given that we have bacteria that are widespread across the planet, with globalisation and the Norwegian public’s increased travels, this is just a dream. But we have a good shot at keeping it down to a low level,” says Bjune.

“Our goal must be to stop the spread to new persons in Norway,” says Arnesen.

-------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling