3-D printed organs may solve organ donation shortages

It was just 10 months ago that a research team at the Wake Forest School of Medicine in the US reported that they had printed out an ear made from living cartilage cells. The ear was kept alive for several weeks in a petri dish and then transplanted under the skin of a mouse, where it grew successfully.

This report, and other clinical trials of cells created by 3D printers, make it clear that the technology is moving full speed ahead. And there’s no time to waste: A worldwide shortage of organ donors means that many people die while waiting for an organ. In the US alone, more than 120,000 people are waiting for organ donations, mainly kidneys. The National Kidney Foundation estimates that 13 Americans die every day waiting for a kidney.

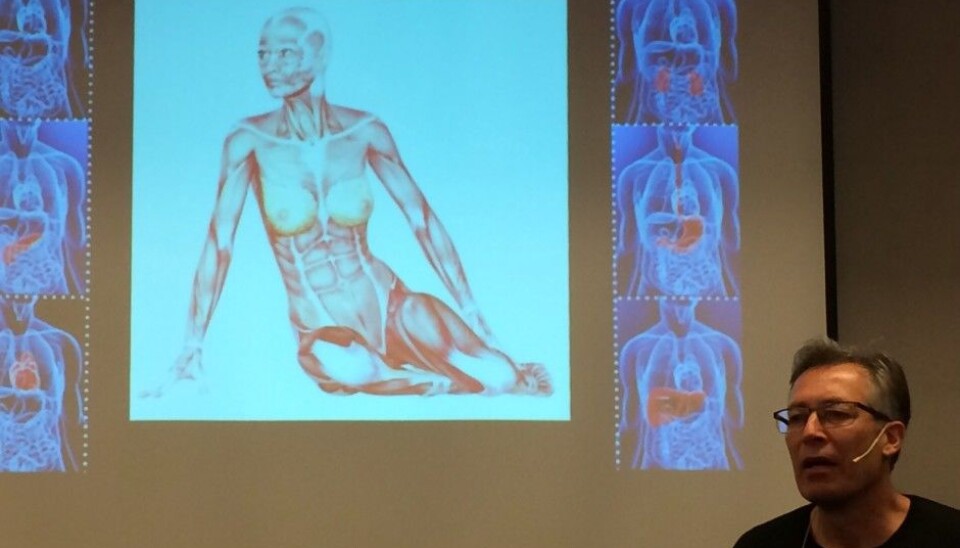

Three-D printer technology “has great potential to allow us to print tissues and organs for clinical use,” said Professor Joel C. Glover at a lecture about the method organized by the Norwegian Biotechnology Advisory Board in Oslo.

Glover is director of the Norwegian Center for Stem Cell Research at the Oslo University Hospital and a professor in the Department of Molecular Medicine at the University of Oslo.

Can print anything

A regular printer can only print on a flat plane, in two dimensions. But it is possible for consumers to purchase 3D printers online and in some stores. One online website devoted to presenting reviews of products did a comparison of 30 different 3D printers available for consumer use.

They’re not cheap, costing around € 3000. But they can be used to print out plastic objects, like toy figures for kids.

“Or you could print out replacement parts for your washing machine,” Glover said. “Some people predict that manufacturers of plastic replacement parts will someday disappear because everybody will be able to print out spare parts at home.”

This fast motion video shows how a 3D printer works:

All that’s needed for these printers is a 3D description what should be printed, and a supply of the material that the printer can use to create the object.

Most parts are currently printed out of plastic, but in principle the printer could be filled with anything.

For the past several years, scientists have used 3D printers to create human jaws and hips out of titanium. The advantage of printing these parts rather than casting them is that the parts are better tailored to each individual patient.

Printing with cells

Stem cell biologists have suspected for years that 3D printing could be used with living material, and wondered if it was possible to print three-dimensional shapes out of human cells, Glover said.

The advantage of printing in three dimensions is that cells develop and retain their proper functions better and longer, he said.

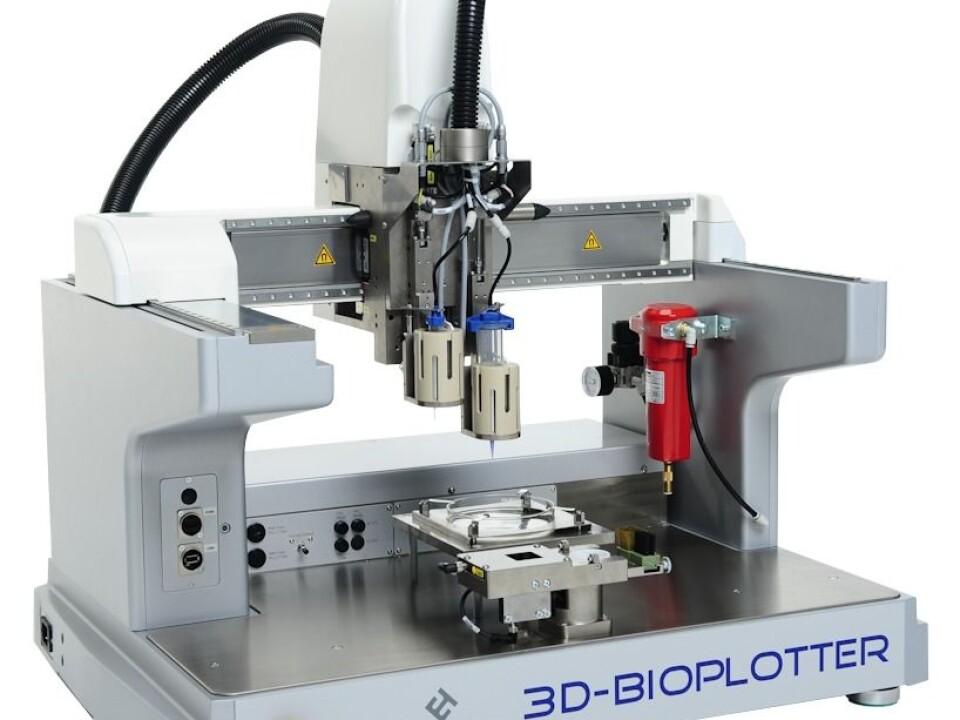

So researchers experimented with creating printer heads that could be filled with a kind of jelly solution containing cells. But it is not easy to print structures made of cells that are able to retain the correct shape after they are printed.

“It is fact very difficult to print out an organ using only cells,” said Glover. “They have to be supported by material around them.”

Scientists thus have to use materials for 3D printing that the cells can tolerate and can grow in, called biocompatible materials. There are many types of these materials, most of which are a material called hydrogels.

Researcher Anthony Atala and his team used a hydrogel when they printed their 3D ear. Atala is a professor at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina in the United States.

“The ear had cartilage cells and embedded channels for blood circulation,” Glover said.

Succeeded in making parts of organs

Researchers have already managed to recreate the structure of the organ they want to copy using a 3D printer, almost down to the single cell level.

They have also managed to make cells divide to create a cell culture. Skin is actually the simplest organ to print using real skin cells. The skin can then be transplanted onto burns. Researchers in other countries have already tested 3D-printed skin in humans.

At the University of Bergen, one researcher has managed to print and transplant living bone tissue into artificial jaws. Researcher, oral surgeon and dentist Cecilie Gudvang Gjerde has used this approach on a dozen patients whose jawbones needed to be built up to support dental implants, according to Teknisk Ukeblad, a Norwegian technology magazine.

Repairing parts of organs first

But whole hearts, livers and kidneys are among the most challenging organs to create with current printer technology. That's because they have a complex structure made out of multiple cell types. But this, of course, is where the need for organs is greatest.

Researchers have, however, managed to print parts of organs, which can be used to repair the patient's body.

By using stem cells from the liver, scientists have managed to emulate some of the liver's functions, Glover said.

They have also managed to create cavities in a gel, which allows cells to position themselves inside these areas.

“In this way, researchers have begun to make parts of organs, which may eventually be used to repair the damaged part of a patient’s organ,” Glover said.

First transplant could be in 5-10 years

Glover estimates the first transplant using a 3D-printed organ will happen in 5-10 years, despite the challenges researchers face.

He believes that the first organ of this type to be transplanted will be a bladder. Urinary bladders have already been created from cells and biomaterials and transplanted into humans.

“The urinary bladder is a relatively simple organ, and will probably be among the earliest clinical goals for this technology,” he said.

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no