How vinyl got its groove back

Has digital sound in CD and PC killed the soul of music? Or are there other reasons why vinyl records are experiencing a steady increase in sales?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

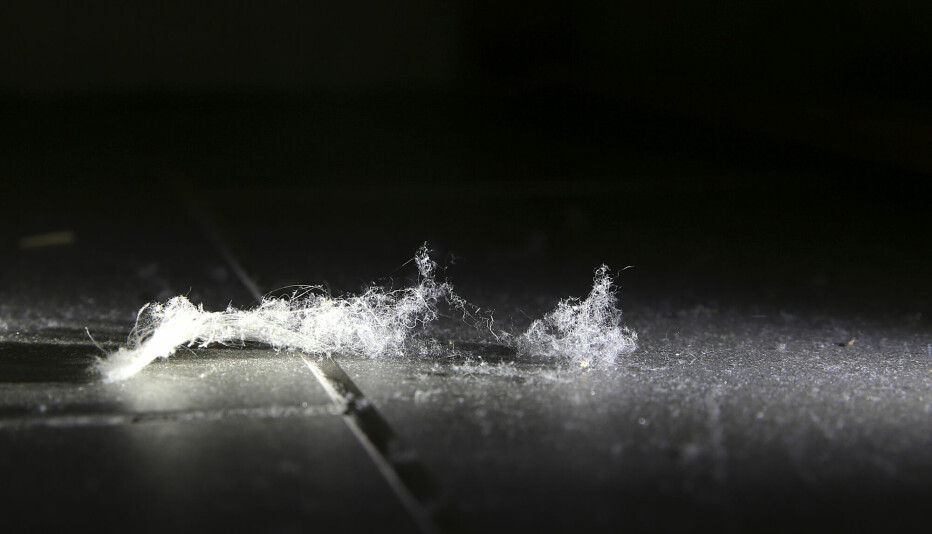

The record slides out of the sleeve with a whisper and settles on the spindle. You drop the needle gently on the black disc. A few discreet crackles in anticipation of the music – and it begins.

It almost sounds like a religious ritual, and for some it comes pretty close. Enthusiasts claim that nothing beats vinyl records for the warmth and range of sound.

Meanwhile, the digital deluge has arrived. Music is chopped into digital bits and streamed, stored and shared through MP3 players, mobile phones, tablets and PCs.

The 2011 Music Industry Report from the Nielsen Company and Billboard showed that digital music sales last year for the first time overtook sales of physical media, accounting for 50.5 percent of all music purchases.

With a total of 1.27 billion sales the 50 percent mark was conquered. It looks like it's digital from here on in.

Except it's not.

The same report shows that vinyl record sales increased for the sixth straight year, shifting 3.9 million albums – up 36 percent from 2010, compared to the modest one percent increase for album and track sales in total. Despite the increasing dominance of downloads, vinyl records are officially the fastest-growing medium in the industry.

The sound of vinyl

So what's going on? Weren't vinyls supposed to slowly spin off into oblivion under the digital onslaught?

“Digital is zeroes and ones, man, anyway you look at it,” as Chuck Leavell, keyboardist for the Rolling Stones, put it in a 2011 interview with Forbes magazine. “Whether it’s a CD or a download, there’s a certain jaggedness to it. Vinyl wins every time. It’s warmer, more soothing, easier on the ears.”

Intuitively it sounds right. Instead of the digital method of mathematically 'interpreting' sound into numerical patterns, on a vinyl record the sound waves are physically imprinted on the surface.

Surely the richness of the sound must be lost in digital translation, as the smooth wave of the analogue signal graph is converted into small 'steps' of digital numbers? Won't this lead to a misinterpretation of the music?

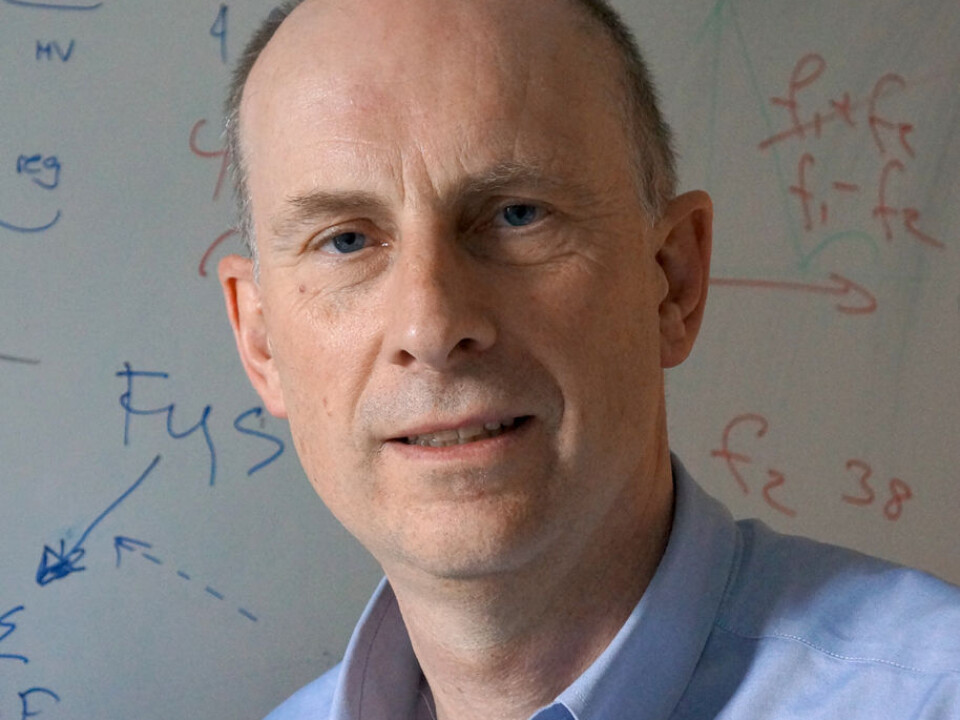

"Not in theory," Sverre Holm, a professor of signal processing at the University of Oslo, told science magazine forskning.no.

"The wave form of the graph can be fully replicated – as long as the sampling includes absolutely every sample of the sound graph before and after the moment you are reproducing."

Millions of samples

A perfectly reproduced sound file would entail that every single sample out of the millions that are gathered needs to be included each time the signal is calculated. On top of this, samples need to be taken 44,100 times per second – which is the standard sampling rate for a CD, to ensure that the sound isn't degraded.

In reality this degree of precision would be pretty much impossible for a CD player, or even a powerful PC. But fortunately we don't need to go to these extremes.

"It's sufficient to sample the values half a second before and after the moment that is calculated. Anything more wouldn't be audible anyway," says Holm.

Getting the jitters

The purists might prefer vinyl, but there are digital sound aficionados out there as well. One of them is Bent Holter, the director of Hegel Music Systems. He has constructed a DAC – a digital-to-analogue converter – to preserve the optimal conversion from numbers back into audible music.

"The main problem is that neither a PC or a CD player delivers the digital numbers at a steady rate. They use a clock which goes slightly too fast or too slow, and causes small errors in the sound called 'jitter'," says Holter to forskning.no.

Jitter can create higher tones which weren't there in the outset, or make the bass murky. Holter's DAC box uses an extremely precise clock to keep the data in a steady stream – removing the anomalies and cleaning up the music.

But unfortunately digital reproduction is not only about what's technically possible. Other factors come into play, as Holm points out:

"What does tend to be a problem is that the music is converted to digital with a lower quality than it should, in order to save on data space. Sound compression such as MP3 and AAC degrades the sound both online and on DAB radio."

Rocking the turntable

Maybe this digital data-stealing is boosting the vinyl renaissance, making people crave a more juicy sound. Sales certainly show that it's not down to nostalgia for yesterday's music.

Last years' top-selling vinyl album may have been an oldie – the Beatles' Abbey Road – but all other albums on the top-ten list were by modern-day artists, including Fleet Foxes, Radiohead, Bon Iver, Mumford & Sons and the Black Keys. Vinyl is not the sound of the past.

And rock is the music to roll on the turntable. Nearly three out of every four vinyl albums sold in 2011 were rock albums.

"Indie rock and heavy metal sounds great on vinyl, but on CDs rough and ready music like that comes across sounding too 'clinical' and tidy," claims store manager Lars Christian Jensen at Soundgarden, an Oslo-based hi-fi specialist shop.

"A vinyl record retains some scratches and dust, and some people feel that's part of the charm," he adds.

So maybe that's the secret of the black disc. There's nothing like a bit of grunge in the groove to get rocking.