Watch the past happen

Warships sailed in Norwegian fjords in 1940. You can now go back in time and follow them through your mobile.

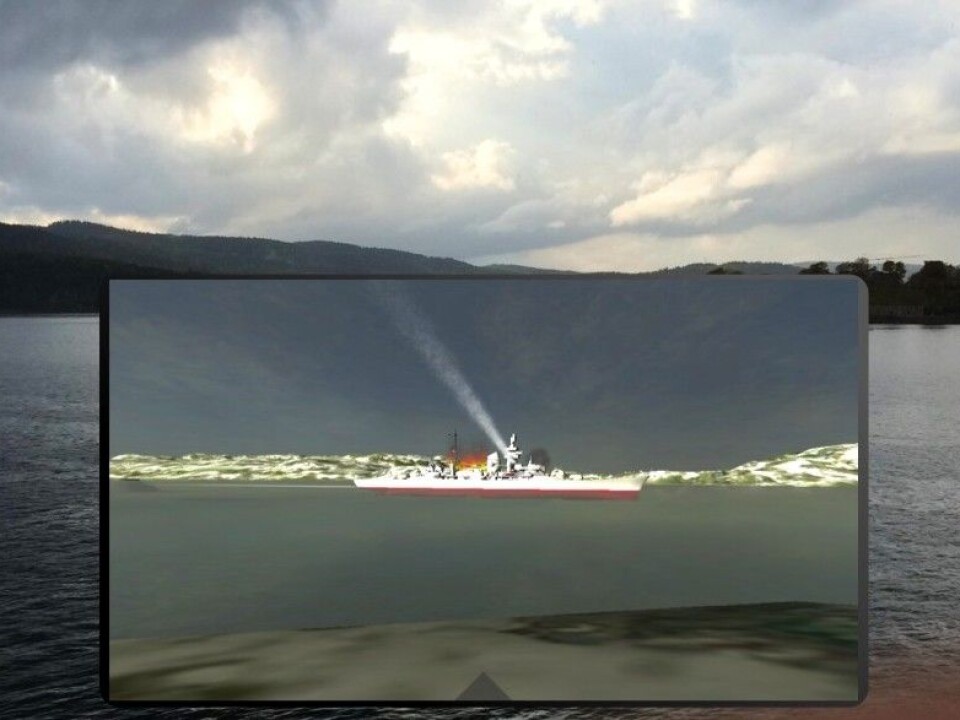

Imagine yourself, in the Blücher app prototype shown above, looking out over the Oslofjord from the town of Drøbak. Pleasure boats leave foamy trails in their wake. You hold up your mobile phone against the waterline, and onto the screen another, larger ship slides into view - the German WWII heavy cruiser.

As you turn to the right, the screen image follows, and Oscarsborg Fortress comes into view. You are 65 years back in time. Black smoke rises and fortress guns give fire.

What does gunfire have to do with the humanities?

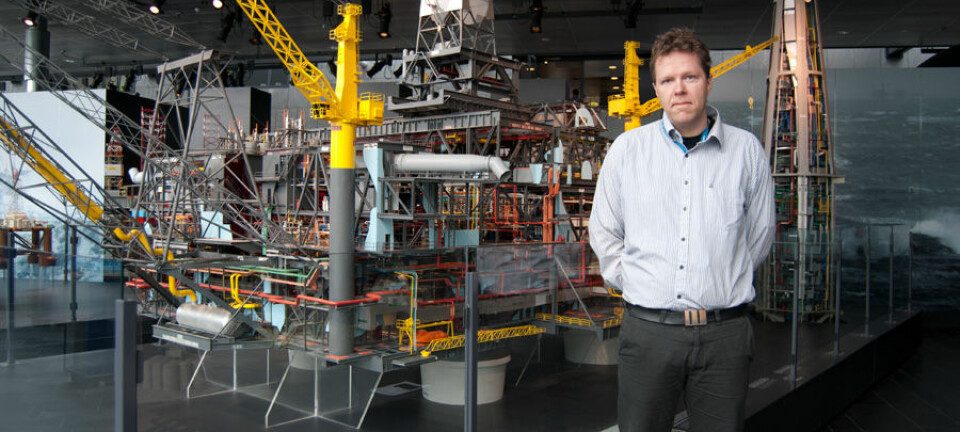

Gunnar Liestøl is on fire, too. He is leading the creation of apps like the Blücher one at UiO’s Department of Media and Communication.

Liestøl wants to show that the humanities involve more than passive analysis, and that they can express themselves actively. He has used some of the theories of the French literary scholar Gérard Genette to develop this prototype.

Genette’s theories of narratology are tools to analyse how narratives are constructed. “We’re turning Genette inside out,” says Liestøl. “Instead of using his categories to retrospectively analyse stories, we’re using them as guidelines for new narrative forms.”

Balancing sequence and access

Years of development portrayed in a few sentences that are read within seconds. Or a moment stretched out over an entire novel. “It's like fast and slow motion film,” says Liestøl.

Duration is one of Genette’s narrative concepts. How much time does the action cover and how long does it take to describe it?

Liestøl gives an example. “You're sitting in the cinema and hearing an exciting story. The story is the sequence. At one point in the story you think: now I'd like to know more about what’s happening. That’s access,” he says.

“So you pull up Wikipedia on your phone. Before you finish reading, you've missed the next part of the action in the film. That’s the dichotomy between sequence and access, storytelling and going into depth,” says Liestøl.

The Blücher app uses this concept to solve a common dilemma in disseminating knowledge. A lot of action happens in the first ten minutes- how can the user keep up? Liestøl holds up the app and zooms in on the German warship. Time stops. Freeze action.

Point at the guns and you find out that they have a range of 33.5 kilometres - more than enough to hit Oscarsborg Fortress.

“This is how you can have access without worrying about losing track of what comes next, or sequence,” says Liestøl.

In the next hour the only action as the ship cruises up the fjord are the crew’s attempts to extinguish the fire on board. In this case, the opposite narrative tactic needs to be applied and the story condensed, or the film would suffer.

New forms of rhetoric

Liestøl is continuing a long tradition of transforming theory into action in the humanities, a tradition that hearkens all the way back to Aristotle in ancient Greece.

Rhetoric—the art of argumentation and persuasion— has been applied to politics and the arts up to the present day. Liestøl believes that we use rhetorical methods in new technology, and that new technology teaches us new rhetorical concepts.

“The influences work both ways,” he says. The Blücher app is just one of several similar apps Liestøl and his research group have created. Several of them can be downloaded to iPhones with iOS and Android phones.

Windows to the past and future

One app allows you to walk around in the Roman Forum in Rome and see where the buildings stood in all their glory around 2,000 years ago.

Another app takes you to Phalasarna, an ancient Greek port city on the northwest coast of Crete. Here you can wander among the ruins and experience the harbour in 330 BCE.

You see ships rocking on the water where there is now is dry land. You see fortifications that were designed to protect against Alexander the Great.

“The apps have been developed with a tool called Unity. The Phalasarna app is now a finalist in Unity Awards, a major international competition. Winners will be announced in Boston on 22 September, Liestøl says.

“These are humanistically-informed experiments with media. Innovation with a humanistic starting point was the basis for the apps. These opportunities have been poorly utilized in humanities research up to now. We want to build on this developing work in the humanities,” says Liestøl.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no