Communities recover quickly from terrorist attacks

Terror attacks can initially cause more ethnic segregation. But things return to normal after three years.

Stockholm, London, Paris, Barcelona, Madrid, Berlin, and New York. These are just some of the cities that have suffered terrorist attacks in recent years.

After each attack the cities responded in the same way: By returning to normality as quickly as possible.

Such display of resilience among the local residents is often reported by journalists in the aftermath of these events—however, scientific evidence of resilience is less abundant, and tend to focus only on people’s attitudes and not their actual behaviour.

Our research provides a rare scientific account of reactions to a terrorist attack, showing that both attitudes and behaviour are subject to resilience.

In a 2016 study published in American Behavioral Scientist, we argued that the tragic events in Madrid on 11 March 2014 triggered a shift in attitudes toward Arab immigrants in Spain. This had repercussions on the migration patterns of Arab born people within and to the country, and caused a significant setback in integration.

But while our analysis documented a clearly detectable shift in migration after the 2004 bombings, we also saw that this shift was only temporary.

Read More: Psychological impacts of terrorist attacks transcend borders

Deadliest terror attack in Spain

On the morning of 11 March 2004, Madrid’s commuter train system suffered a series of bombings.

Four commuter trains where hit around 7:40 a.m. with a total of ten bombs, killing 191 people and leaving close to 2,000 wounded. It was the deadliest terror attack ever in Spain and one of the bloodiest in Europe.

Islamic fundamentalists had masterminded the bombings and several of the offenders were of North African origins. As Spain became a target for Islamist terrorism, Spain’s Arab minority group drifted into the centre of attention, politically as well as socially.

Read More: Lone-wolf terrorists can be tracked

Immigration to and within Spain

In order to see if and how ethnic segregation of this group changed following the attack, we estimated the local immigrant densities for each quarter in the period leading up to and after the bombings.

Between January 1999 and 2010, there were 5.4 million international migration events—this includes all instances of immigration to Spain and could include multiple migrations by some of the same individuals. Another 13.9 million inter-municipal migration events took place within Spain’s 52 provinces—3.8 million of these, were foreign-born internal migrants.

The data were obtained from the Estadistica de Variaciones Residenciales assembled by Spain’s National Statistical Agency (INE), and include movements of undocumented immigrants.

The total population of migrants from Arab countries was approximately 460,000 at the time of the attack, reaching 910,000 in 2010.

Read More: Appreciating life more after a terrorist attack

Reversal in immigration after the attack

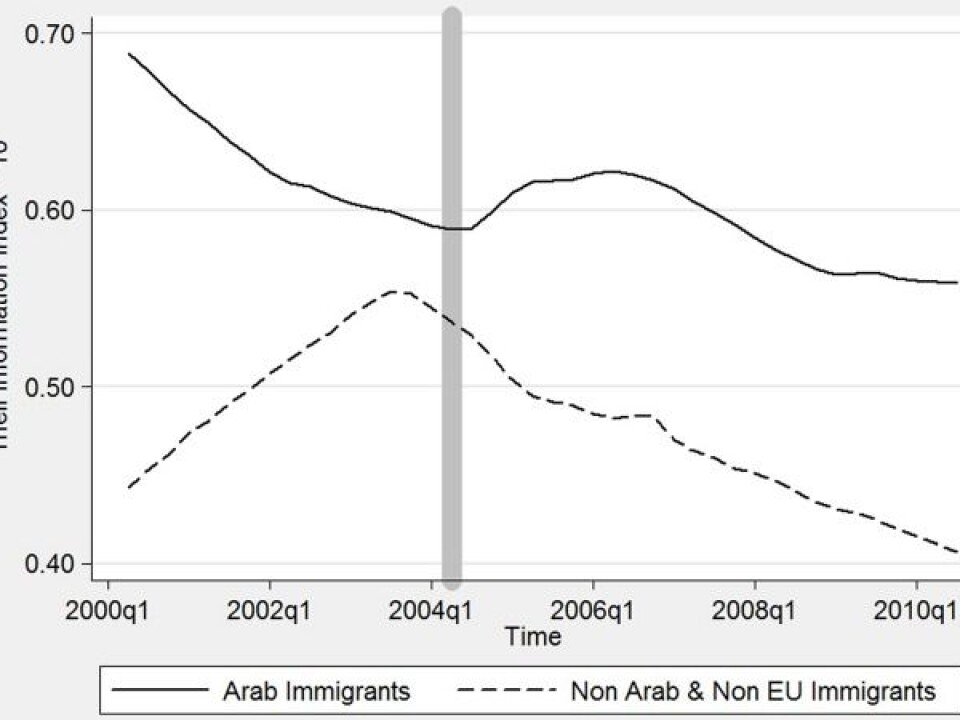

We used these data to estimate the change in integration during this period, as shown in the graph below. Here we plot the Theil Information Index, which shows the change in the mix of two groups over time. The index varies between zero (maximum integration, when all provinces have the same composition as the nation at large) and ten (maximum segregation, when all provinces contain only one group).

Before the 2004 terror attack, the index shows a clear tendency toward increased integration of the Arab sub-population, with a low score indicating a more evenly distributed minority group across Spain.

But at the time of the attack, the trend is suddenly reversed and the country becomes more segregated, increasing by 2.5 per cent in late 2005 compared to the second quarter of 2004.

However, this did not last long. Three years later, roughly at the time when Spain’s economy came to a full stop, the index score had returned to pre-attack values.

The temporary nature of this shift in integration, suggests system resilience in the face of external shocks.

Read More: Terror and Trump have transformed Norwegian travel habits

Arab integration unrelated to wider trends in immigration

But how do we know that these trends in integration are actually related to the 2004 bombings and not to some other, wider trend in immigration?

To assess this, we compared the integration of the Arab sub-population with immigrants from other, non-European countries.

We saw that the increased segregation experienced by Arab migrants was unique to this group, and did not occur in other non-European groups. This implies that the changes we saw in the immigration and integration of Arab migrants were not the result of a general change in attitudes toward immigrants in Spain.

This supports our hypotheses that integration of the Arab minority group was negatively affected by the terror attack and that the Madrid bombings obstructed the integration of the Arab population in Spain, albeit only temporarily.

Read More: Swedish police and emergency personnel feel poorly prepared for terrorist attacks

Arab populations stuck together after the attack

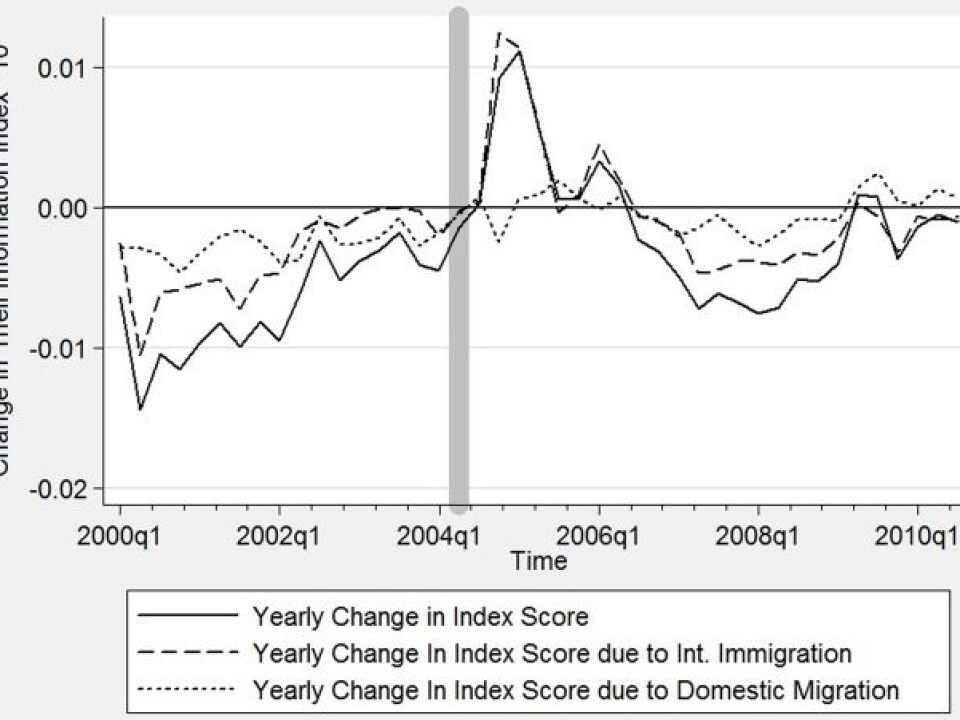

To get a more detailed picture of integration before and after the attack, we analysed the type of migration in the country—internal or international.

In the figure above, we can see that increased segregation is driven largely by immigration into Spain, and to a lesser extent by internal migration within the country.

In other words, in the period immediately after the bombings, new immigrants from the Arab world were more likely to settle in areas were Arabs already lived. This type of movement is expected when attitudes against a minority groups is hardening and when this group may have good reasons to fear discrimination.

This means that ethnic segregation increased between Arab immigrants and native Spaniards shortly after the terror bombings, but again the effect was only temporary. No such effect was found for other immigrant groups.

Read More: "Extremism is a research ethics minefield"

We do become segregated after a terror attack… but we recover

It should be emphasised that this analysis is based on highly aggregated data from the 52 provinces of Spain. We would expect to see even more dramatic changes with more fine-grained data from municipalities and individual neighbourhoods, because migration within provinces is likely to also impact on integration.

However, and this is perhaps the most important finding: our empirical analysis showed that this was a relative short-term effect.

After just two years, ethnic integration started to increase again in Spain, and thus resumed the positive trend that was observed in the years before the terrorist bombing. And, as mentioned earlier, after three years it had returned to pre-attack values.

This observation in itself is an indication of how resilient society can be against terrorist attacks.

---------------

This article is based on a blog post originally published at Socio(b)log. Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk.