Could the video assistant referee system replace referees in football?

ASK A RESEARCHER: Referees make mistakes, but thanks to goal-line technology and video refereeing, these errors can be avoided. Maybe it's time to ask: Do we need referees at all?

Top-level football referees have recently benefitted from various new technologies. With goal-line technology, referees no longer have to second-guess themselves on whether the ball went into the goal or not.

In addition, several leagues have adopted VAR - video assistant referee, in essence a form of video judging. A VAR review allows the referee on the field to get advice from one or more referees who can analyse and replay video images of the situation at question.

That means if the referee is in doubt whether a player was offside or if a foul was serious enough to warrant a penalty, VAR can step in and give the referee a definitive answer. The technology can affirm a referee’s decision or it can reverse a referee’s error.

It’s easy to conclude that this technology should of course be used and that it will make life easier for everyone. Yet criticism of VAR hails from all sides. Some people believe the decisions will still be wrong, while others believe it will ruin the flow of the game.

So, what do researchers think?

Why we need VAR

First: what speaks in favour of video judging and other refereeing technology?

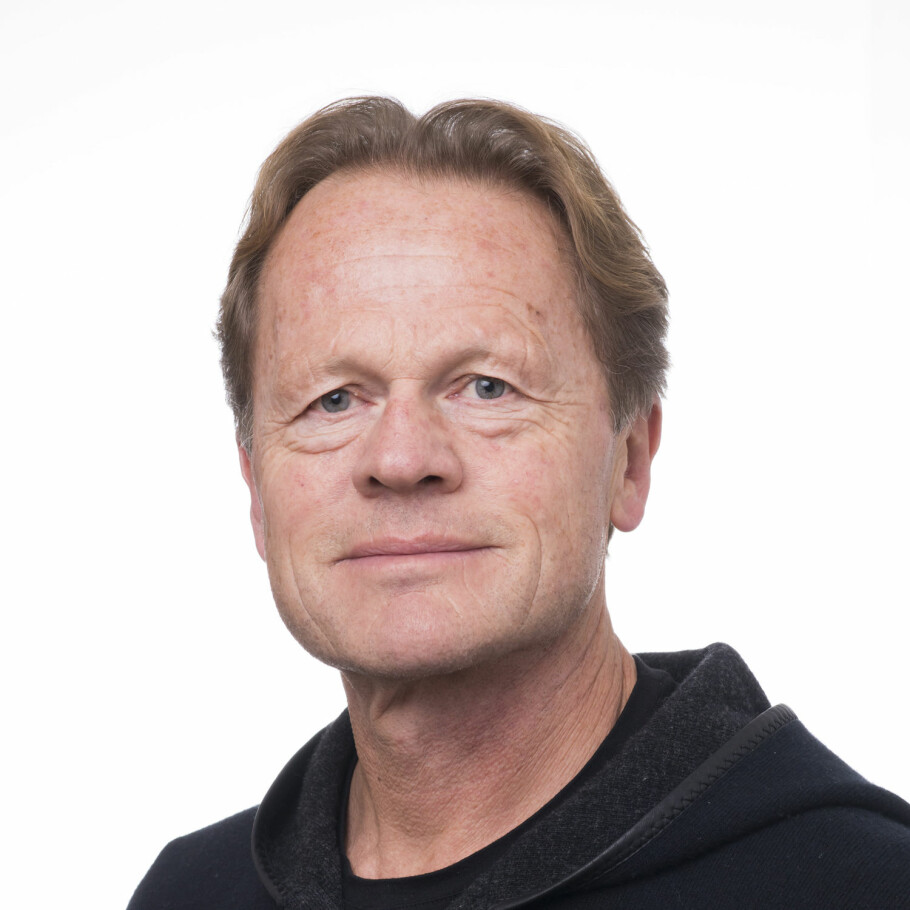

“Referees are just human beings, and we’ve had some startling research findings on referee decisions,” says Sigmund Loland. He is a professor at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and has researched ethics in sports.

Loland says that referees tend to judge in favour of the home team. They also keep an eye on players with a bad reputation. And if one team was awarded a penalty earlier in the game, they can compensate by awarding a penalty to the other team later. Some researchers believe that referees are more likely to judge in favour of players and teams wearing red jerseys.

Referees are limited by the same restrictions as everyone else:

“This is a complex game. There are lots of bodies moving at a quick pace. You have a tenth of a second to make a decision, so obviously referees can make mistakes,” says Loland.

But it gets bad when the mistakes hit some more than others.

Referees can be influenced

“We’ve documented in studies that the distribution of misjudgement isn’t random,” says Bjørn Tore Johansen.

He is a professor at the University of Agder, and his research includes studying football referees. In one study conducted by Johansen and his colleagues, their findings revealed that referees often decide in favour of high-status teams and players.

Johansen cites the 2018 World Cup match between Denmark and Australia as an example of this. Denmark led 1-0, but then the Australians called for a penalty, which the referee overlooked until a VAR review determined that it actually was a penalty situation. Australia was finally awarded the penalty, and the match ended 1-1.

Johansen points out that referees, just like the rest of us, can thus be influenced. For example, if we have to make a decision, it’s easy to choose the lowest cost solution. For a referee, that might mean calling a penalty in favour of the home team, or maybe not calling a penalty in favour of the away team.

In principle, these factors can be counterbalanced by video judging. If the referee has made a mistake, the decision can be reversed after more detailed analysis.

“That's why I'm for VAR, because you get fair decisions,” says Johansen.

Loland points out that the sport also becomes much more transparent with video judging.

“VAR makes it harder to get away with things. Now you see every little thing that happens, everything from spitting on or hitting players, pulling jerseys and so on. The players’ actions are revealed to a much greater extent now than they used to,” says Loland.

But even if referees have their weaknesses, neither Loland nor Johansen want to remove them from the field in favour of the new technology.

Why we need human referees on the field

Loland believes referees are necessary and important because technology will never eliminate doubt. “The technology allows the task to be solved more precisely, but it doesn’t get any less complex,” he says.

“There will always be a need for match officials, and technology can never be a substitute, because situations aren’t black and white. Referees need to exercise discretion,” says Johansen.

Loland points out that offences that happen on the field are varied. Even if a player is lying on the ground and howling in pain, there may be various reasons for why he or she ended up there. Did an opponent commit a reckless tackle, or did the player trip over his or her own feet, accidentally crash into another player – or is he or she just feigning injury? The reason may be the difference between anything from a penalty kick to a yellow card for diving. The researchers believe that so far, human eyes are needed to make this assessment.

They agree that the hallmark of a good referee is being able to manoeuvre this challenging and quick-moving landscape.

“Good referees are experts at understanding human behaviour,” Loland says.

“The role of the referee has changed a lot in the last decade. A referee used to be able to be rule-oriented, authoritarian and hardly needed to communicate with the players. Now you have to sell your decisions and communicate in a completely different way. You have to explain the background for the decision,” says Johansen, who is a football referee himself.

Why is VAR so controversial?

One of the reasons VAR has faced so much criticism, Loland believes, is because the ways in which the technology is to be used has not been made clear enough. For example, players are not allowed to ask the referee for a VAR review, but we still see dissatisfied players give the referee the signal for VAR when a situation doesn’t go their way.

“For outsiders, spectators and sometimes players, VAR seems a bit random and chaotic. Implementing the technology has to be done properly,” says Loland.

It’s also not unusual to see furious managers after a decision has been made. This despite the fact that video judging is supposed to provide a more precise analysis of the game.

Johansen believes this indicates that players and managers have failed to properly understand the rules of video refereeing.

Understands frustrated supporters

Johansen partly agrees that video judging takes too long and breaks up the game.

“In England it takes too long, but that's because they only have one VAR referee. Looking back to the World Cup in Russia, where they spent a long time preparing and had several referees, it worked well,” he says.

In the course of 64 matches, 457 situations were assessed, but no more than a dozen of them were passed on to the referee on the field, he points out.

But he still understands the frustration spectators feel.

“For some spectators, VAR has taken away the spontaneous cheering after a goal – now you have to wait and see if the goal is confirmed or not. So yes, the immediacy and spontaneity disappears. But I’m enough of an optimist that I think we’ll get used to it, like so much else. It took a while before we learned to accept the offside rule when it was first introduced in football, too.”

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no