An article from NIVA - Norwegian Institute for Water Research

The case of the vanishing pollutant

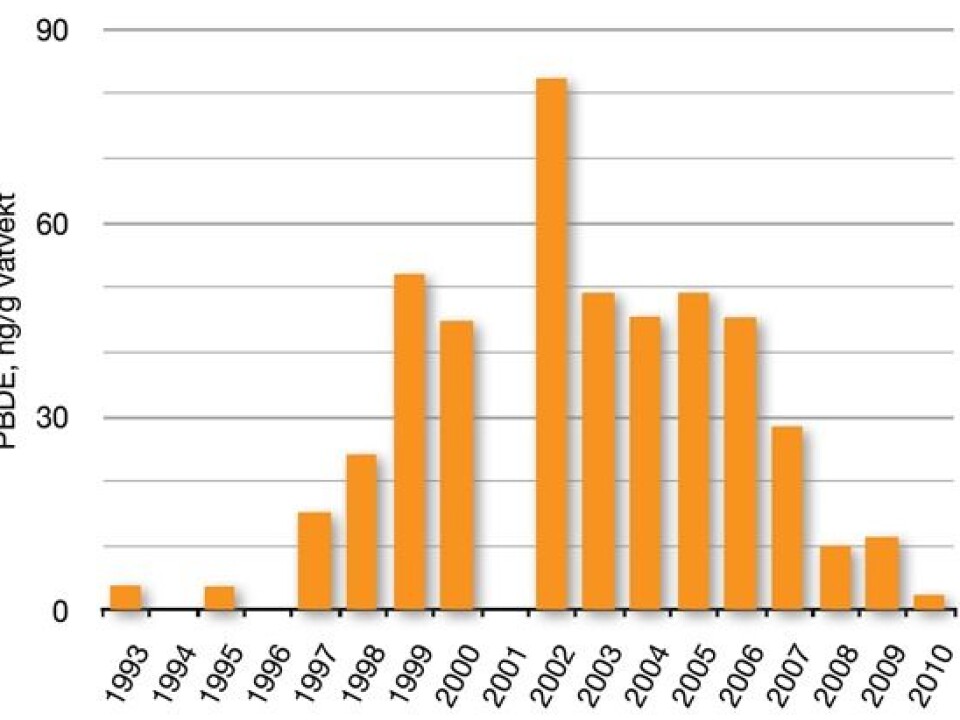

Ten years ago trout in Norway’s largest lake had the world’s highest measured levels of the environmental pollutant PBDE. Now their levels are about the same as before the sizeable discharges started in the 1990s.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Levels of the pollutant in the fish are now 5–10 percent of the highest levels registered in the early 2000s, concludes a new study conducted by the Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA) and the Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU).

In 2001 NIVA researchers discovered record levels of the brominated flame retardant PBDE in the fish in Lake Mjøsa. This was the first study of this pollutant in Norwegian freshwater.

The findings were confirmed in a follow-up study two years later: brown trout from this lake had PBDE concentrations that topped the charts internationally.

That prodded environmental authorities to initiate a monitoring programme to identify the sources of the pollutant. The likely suspect was a textile company in Lillehammer that used PBDE in its products.

Suspicions were confirmed when sediments in Mjøsa and the factory’s effluents were investigated. By then the use of PBDA had already been halted.

Discharges since the mid-1990s

Researchers also tried to find out when this specific pollution of Norway's largest lake started. The answer came from frozen fish and sediment samples. Emissions started when the textile firm started using the flame retardant in the mid-1990s.

Researcher Eirik Fjeld at NIVA explains: “Fortunately we had frozen samples of the whitefish vendace that were caught in Mjøsa in the early 1990s. A foresighted scientist had archived material of this herring-like fish in the salmon family in order to chart its pollution history.”

Samples were also taken of sediments in Mjøsa. The environmental pollutant PBDE is nearly insoluble. But it combines with organic particles in water and sinks to the bottom with them.

In deeper areas the sediments are deposited evenly as time passes. Core samples were taken and these enabled scientists to both date the years of various layers and measure the concentrations of environmental toxins.

Concentrations have plunged

When the use of PBDE was stopped in 2003, researchers tossed out a range of estimates about how long the fish would retain high concentrations of the pollutant. The most pessimistic suggested the problem could plague the lake for nearly 30 years.

However, concentrations of brominated flame retardants in vendace already started to fall in 2007.

Measurements carried out in 2011 show concentrations close to those from the beginning of the 1990s, i.e. when the large emissions in Lillehammer started. Levels in both vendace and trout concentrations are now just 5–10 percent of the highest levels registered ten years ago.

"This is a positive surprise,” says Fjeld.

Is the lake healthy now?

Even though flame retardants and some other known environmental pollutants in Mjøsa are now past history, the lake is still impacted by harmful substances stemming from airborne pollution and local sources.

“New, potentially damaging products and compounds for the environment are constantly popping up. The case of the flame retardants in Mjøsa just goes to show how important it is to continually monitor our water resources,” says Fjeld.

Classical environmental toxins haven’t gone away. For instance mercury concentrations in trout are still alarming. Following a steady decrease since the 1980s, concentrations spiked in 2006. The reason is still a mystery.

When trout reach a size of over two kilos there’s a good chance their mercury levels are above the ceilings set for human consumption by Norwegian and EU authorities. Predatory fish such as pike, perch and burbot can also contain too much mercury. In addition, large-bodied brown trout can have disturbing levels of PCB and dioxins.

Internasjonal ban

After the pollutant was found in Lake Mjøsa, Norwegian environmental authorities campaigned actively for an international ban of PBDE.

In accordance with Norwegian proposal, the two predominant groups of PBDE have now been included in the Stockholm Convention, a global agreement to protect health and environment against persistent organic pollutants. The EU has also initiated a ban on the use of these compounds.